Tule Lake descendants, Fair Play Committee member relay words, deeds of resistance.

By George Toshio Johnston, Senior Editor

What Richard Katsuda told the capacity crowd in Los Angeles’ Japanese American National Museum main hall encapsulated the several Day of Remembrance events taking place in mid-February.

It was a simple message of purpose applicable to all DOR ceremonies: to “remember that over 125,000 Japanese Americans were imprisoned” by their government as a result of an American president’s executive order dated Feb. 19, 1942.

(To view the Pacific Citizen’s coverage of the 2023 Los Angeles Day of Remembrance, click here.)

But at this DOR gathering, the focus was on the grievances suffered by those incarcerees who resisted — and as a result suffered from the federal government’s brutish tactics to quell the dissent caused by the abrogation of their rights.

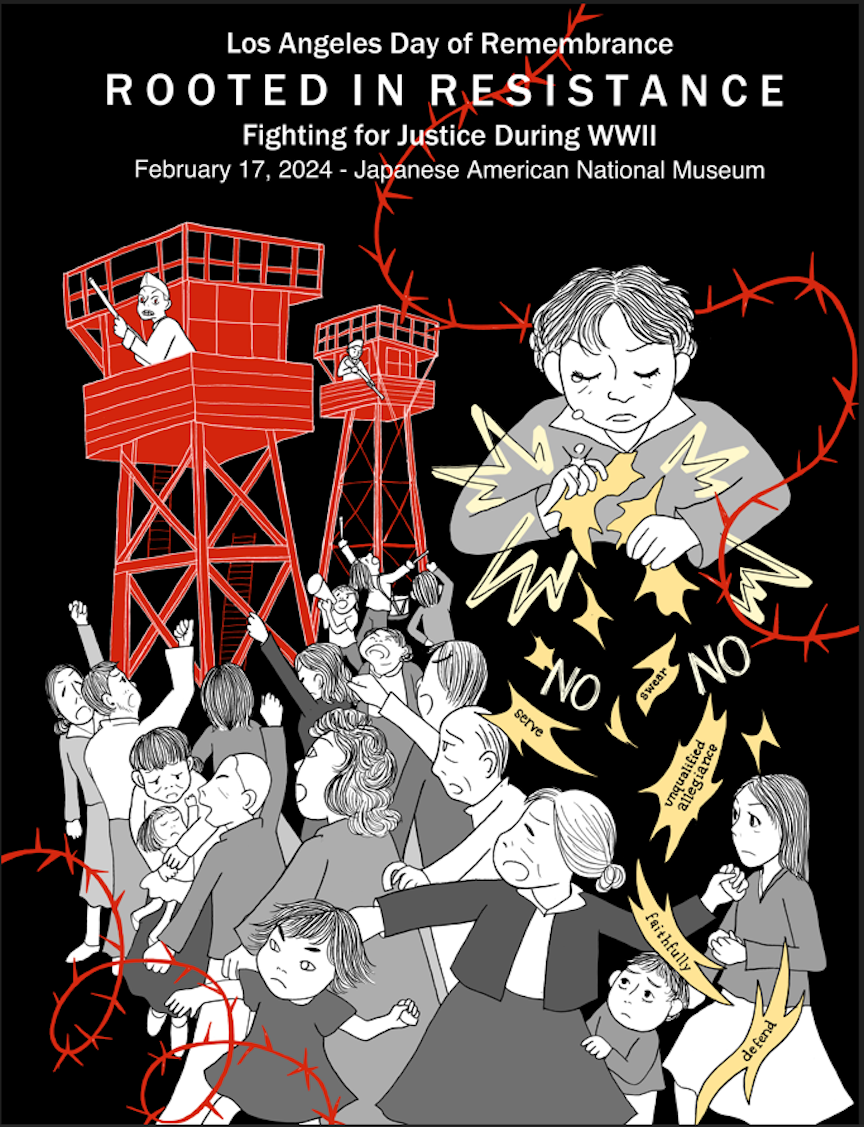

Katsuda’s remark was made on Feb. 17 during the Stories of Resistance portion of the program, before introducing four speakers whose addresses fit the 2024 DOR’s theme: “Rooted in Resistance: Fighting for Justice During WWII.”

Speaking at the 2024 Day of Remembrance (from left) were Takashi Hoshizaki, Kyoko Nancy Oda (via recorded video), Diana Tsuchida and Soji Kashiwagi. (Composite photo: George Toshio Johnston)

The speakers were Dr. Takashi Hoshizaki, one of the 63 members of the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee; Kyoko Nancy Oda (via a recorded video), who was born in the Tule Lake Segregation Center — formerly the Tule Lake WRA Center — and whose Kibei-Nisei father, Tatsuo Inouye, was placed in the camp’s stockade; Diana Tsuchida, granddaughter of Kibei-Nisei Tamotsu “Tom” Tsuchida, who was originally incarcerated at the Topaz WRA Center and later removed to Tule Lake; and Soji Kashiwagi, son of playwright Hiroshi Kashiwagi, described by Katsuda as the “poet laureate of Tule Lake.”

The four speakers were preceded by a recording of historian Yuji Ichioka testifying at a Commission on Wartime Relocation and Incarceration of Civilians hearing. Due to a technical malfunction, however, only the audio was presented to the audience, and the video portion of the recording was not shown. (The visual portion of Ichioka speaking was added in postproduction to the streaming YouTube video of the event.)

Hoshizaki, 100, noted the stance of the FPC, which he said was “give to us our civil rights, and we will gladly serve” in the U.S. military, which would create complications for those men of draft age. Regarding the infamous loyalty questionnaire that was circulated through the WRA camps, he said he answered “yes” to question 27 and “no” to question 28, which made him a “yes and a no boy.” Along with the other resisters, he was sentenced to three years in a federal penitentiary, but he was released after serving two years in prison at McNeil Island in Puget Sound.

Program cover for the 2024 Los Angeles Day of Remembrance.

After President Truman pardoned the resisters, Hoshizaki attended Los Angeles City College and the University of California, Los Angeles. Noting how he was still young enough to serve in the Armed Forces and having received his second draft notice in spring 1953, he said there were about six others among the Heart Mountain resisters who would eventually serve in the Army.

“Now that we had our civil rights back and we were released from the concentration camp, we gladly served,” Hoshizaki said. He went on to serve for two years as a medic at Fort Hood in Texas, which made him eligible for the GI Bill, which he used to continue his studies at UCLA.

Speaking via a recorded video, Oda spoke of her father, Tatsuo Inouye, who had demonstrated judo at the 1932 Olympic Games in Los Angeles. A storekeeper in L.A.’s Boyle Heights area when Executive Order 9066 went into effect, the Inouye family was originally incarcerated at Arizona’s Poston and transferred to California’s Tule Lake after he answered the same loyalty questionnaire Hoshizaki — and thousands of others — had been given. “For question 27, he answered ‘no’ because he had family in Japan. So, for question No. 28, he answered neutral because he was a transnational citizen, who actually answered truthfully,” Oda said of her father.

Later, while incarcerated at Tule Lake, Oda said, “My father was arrested without charges in front of my mother and sisters and rushed to the stockade with bayonets. He said, ‘I cannot fight, but I will write.’ During this November to February, my parents exchanged 33 letters.”

She noted that her father participated in a failed hunger strike to protest the awful conditions the stockade prisoners endured. In her closing remarks, Oda said, “Unlike many, he and my mother chose to tell me their story. Tuleans are still outcast and discriminated by our own community. That must stop. Today, we Tuleans are no longer silent. Our community must live in peace.”

Tsuchida described her Kibei grandfather as someone who was not an “extraordinary or exceptional man when it came to being someone of significance to the community.” Born in Loomis, Calif., Tamotsu Tsuchida was taken to his father’s hometown in Kumamoto, Japan, returning as an adult to San Francisco where he became “an active member of the Buddhist church, and he was starting to run his own employment agency and living a relatively simple life in Nihonmachi.” That changed with WWII.

Originally incarcerated at Utah’s Topaz WRA Center, Tamotsu Tsuchida would answer “no” to 27 and 28 of the loyalty questionnaire — which put him on the short list for Tule Lake.

But before that happened, Tsuchida said her grandfather fought a fellow Topaz resident over an anonymous op-ed that appeared in the Topaz Times camp newspaper that he thought was directed at him. The altercation detoured him to the citizen isolation center in Leupp, Ariz., before rejoining his family at Tule Lake.

Tamotsu Tsuchida was on the verge of renouncing his and his wife’s U.S. citizenship and moving to Japan until a friend persuaded him that going to a war-torn, hungry, defeated and atom-bombed Japan wasn’t the best course of action.

In 1981, he was able to testify at a CWRIC hearing. His granddaughter quoted him as saying, translated from Japanese, “He said that the U.S. government must have known that in a postwar era, there would one day be a political reckoning about the government’s wartime actions. It was obvious that if a particular ethnic group was targeted, the government would need to take responsibility for such discriminatory action and pay restitution.”

Serving as the caboose of the four speakers was Kashiwagi, wearing a hat once worn by his late father in the 1950s as a UCLA student, a hat that would make him appear “eccentric and weird enough so that no other Nisei on campus would ever bother talking to him.”

The reason: It was a way to avoid the loaded question Nisei of that time would inevitably ask each other: “Which camp were you in?” The hat tactic worked, and he didn’t have to be bothered and burdened with the “stigma of being that no-no, a disloyal, a troublemaker” from Tule Lake.

It was a topic that wasn’t discussed in the Kashiwagi household. “I remember my dad was one of the few Nisei in San Francisco who was actually out there talking about camp — but not Tule Lake or being a no-no. Not in public. Not at home. It was one of those dark family secrets locked away in a closet, never to be opened,” Soji Kashiwagi said, even as he wondered why his father wasn’t a member of the 100th/442nd. “I didn’t ask, and he didn’t tell because that’s the way it was.”

Soji Kashiwagi began to better understand his father after attending a Tule Lake pilgrimage, when he began to see his father in a new light.

“My dad said he was always loyal to America and would have proudly fought for his country, if his country released him from camp and gave them his rights and freedom back. ‘How dare you put me in camp and then question my loyalty,’ he said. ‘I am already a loyal American. I don’t need to prove it to you or anyone else.’ And there it was — the truth. . . . He said no and no to those questions. And he had every right as a citizen to do so.”

Michael Murata sings and plays a keyboard at the Feb. 17 Day of Remembrance at the Japanese American National Museum. This year’s theme was “Rooted in Resistance.” (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

The program began with Michael Murata singing and accompanying on keyboard his original composition, “Okagesama De,” followed by remarks from JANM CEO and President Ann Burroughs and L.A. DOR Committee member and JACL Education Programs Manager Matthew Weisbly.

Left to right photos: JANM President and CEO Ann Burroughs speaks at the Feb. 17 Day of Remembrance in Little Tokyo. JACL Education Programs Manager and Los Angeles DOR Committee member Matthew Weisbly addresses the audience. 2024 Los Angeles DOR Committee members Nancy Takayama, representing JACL, and Glen Kitayama, representing the Manzanar Committee, address the audience at the Japanese American National Museum. (Composite photo: George Toshio Johnston)

DOR Committee members Nancy Takayama and Glen Kitayama then announced the camp roll call, in which a procession mostly comprised of surviving Japanese American incarcerees or descendants of incarcerees made their way to the front of the stage, accompanied by a Boy Scout from Troops 242, 365, 738 or 764, or a Girl Scout from Troop 12135, each bearing an affiliated banner.

(From left) Hank Oga represents Rohwer, Esther Taira represents Topaz, Richard Murakami represents Tule Lake, Ed Nakamura represents the 100th/442nd/MIS and Dan Mayeda represents Tuna Canyon. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Participating in the procession were:

- June Ruriko Tearstan, Amache Colo. (WRA)

- Carrie Morita (descendant of a Gila River survivor), Gila River, Ariz. (WRA)

- Hal Keimi, Heart Mountain, Wyo. (WRA)

- Kanji Sahara, Jerome, Ark. (WRA)

- Pat Sakamoto, Manzanar Calif. (WRA)

- Kiyo Fukumoto, Minidoka, Idaho (WRA)

- Grace Oga, Poston, Ariz. (WRA)

- Hank Oga, Rowher Ark. (WRA)

- Esther Taira, Topaz, Utah (WRA)

- Richard Murakami, Tule Lake, Calif. (WRA)

- Ed Nakamura (100th/442nd/MIS)

- Daniel Mayeda (descendant of a Tuna Canyon survivor), Tuna Canyon Detention Station (DOJ)

June Ruriko Tearstan, representing Camp Amache, aka the Granada War Relocation Center, is accompanied by a Boy Scout banner bearer from Troop 738 on Feb. 17 in Little Tokyo at the 2024 Day of Remembrance. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Murata returned to the stage with Miko Shudo to perform “Don’t Fence Me In,” which was popular during the time of incarceration. Joy Yamaguchi and Jan Tokumaru followed with the In Memoriam portion of the program, honoring recently deceased people who, as Tokumaru put it, “contributed uniquely to highlighting and preserving our community and this history.”

Those commemorated were Fred Bradford, Karen Ito Edgerton, Alan Furutani, Itsuki Charles Igawa, Mary Karasawa, Bob Moriguchi, Martha Nakagawa, Alan Nishio, Wilbur Sato, Cathy Tanaka, Minoru Tonai, Rosalind Uno, Amy Uyematsu, Mike Watanabe and Gayle Hane Wong.

Tonai, Nakagawa, Nishio and Uyematsu each received additional accolades from, respectively, John Tonai, son of Min Tonai; author Naomi Hirahara; Evan Lockwood, grandson of Alan Nishio; and Carrie Morita, who paid tribute to Uyematsu by reading excerpts from one of her books, “36 Views of Manzanar.”

Closing remarks were from DOR Committee member and JANM public programs associate Elizabeth Morikawa.

(Note: The video of the 2024 Los Angeles Day of Remembrance may be viewed at tinyurl.com/2zxzszzt. The program can be viewed at tinyurl.com/4ed2m562.)

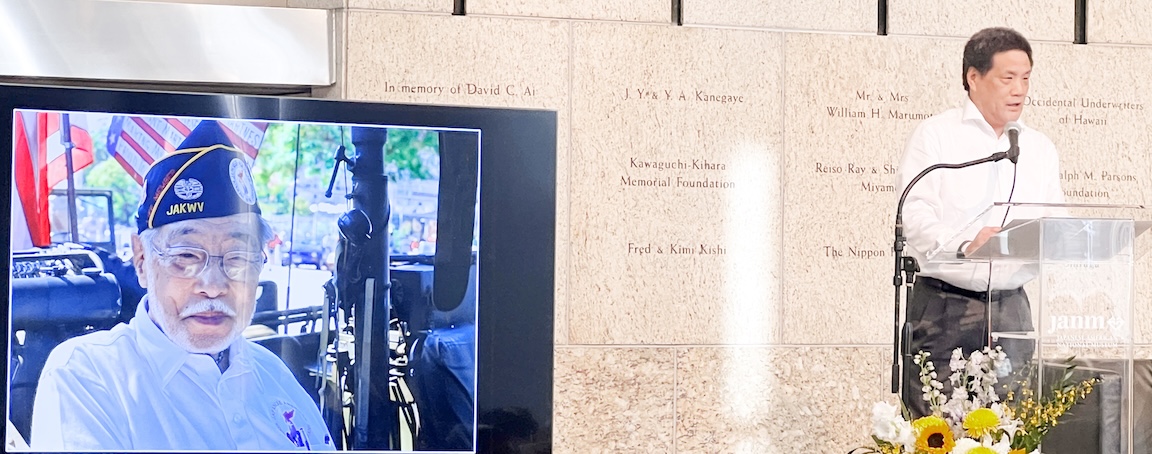

John Tonai pays tribute to his father, the late Min Tonai, seen on the video monitor during the In Memoriam portion of the program, which also honored Alan Nishio, Martha Nakagawa and Amy Uyematsu, who all died in 2023. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)