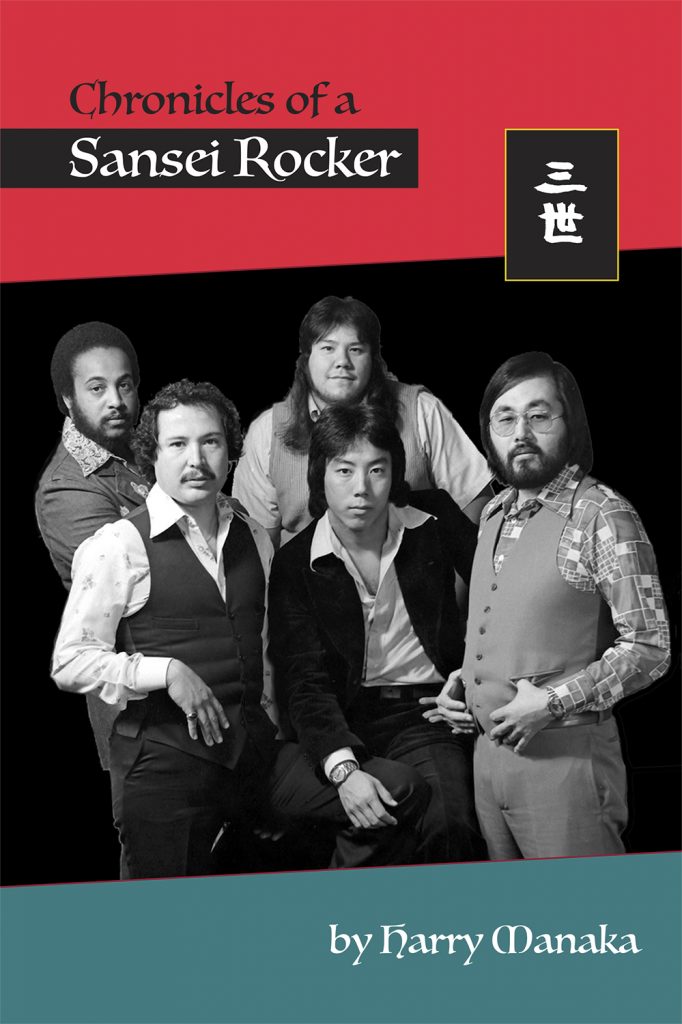

Somethin’ Else: Vocalist Royce Jones, bassist Bob Flores, guitarist David Jingu, drummer Nick Urrutia and keyboardist Harry Manaka. (Photo: Courtesy of Harry Manaka)

Harry Manaka’s ‘Chronicles of a Sansei Rocker’ hits rewind.

By George Toshio Johnston, Senior Editor, Digital & Social Media

‘Get back,

Get back,

Get back,

Get back to where you once

belonged’

If you do not recognize those lyrics from the Beatles’ “Get Back,” then you’re probably neither a Baby Boomer nor a Beatles fan.

But if, upon reading those words, that song started playing in your mental jukebox and you were a young Japanese American who grew up in and around Los Angeles during the 1960s and ’70s, then you are likely in the target demo for a new self-published book documenting the “Sansei dance party circuit.”

“Chronicles of a Sansei Rocker” is Harry Manaka’s book on the Sansei dance band era of the 1960s and ’70s and his part in it as a member of Somethin’ Else. Manaka is on the right. (Photo: Courtesy of Harry Manaka)

Even if you don’t fit that profile, “Chronicles of a Sansei Rocker,” written by Monterey, Calif.-born and Long Beach, Calif.-raised Harry Manaka, is a window into the time when it seemed like every neighborhood from coast to coast had its own resident rock bands that tried to attract the opposite sex and maybe make a few bucks playing gigs as they tried to emulate the pop music of the British Invasion, American rock ’n’ roll acts and, of course, Motown.

In a sense, “Chronicles” is Manaka’s way to “get back” to the time and place where he once belonged, when his band, Somethin’ Else, was among the many music acts not just in Los Angeles in general but within the area’s Japanese American and Asian American cohort.

Now 73 and 11 years into retirement following 30 years of government service, Manaka was inspired to preserve his recollections of that time for this children and grandchildren — and, as has turned out, hundreds of others who learned of his book through word of mouth and social media. Turning those memories into a book got an unexpected boost from the Covid-19 pandemic lockdown.

“As horrible as it’s been, it has kind of been an opportunity, disguised as a tragedy,” Manaka said, referring to how the “safer-at-home” health protocols were the fillip needed to get him started on turning those reminiscences into words and then, with photos, into a book. “I thought, ‘If not now, when?’ and started jotting down some thoughts and memories from my younger days.”

While Manaka was the one driven to turn those thoughts into a book, he did, to paraphrase (and again refer to) the Beatles, “get a little help from his friends”: Mary Uyematsu Gao, who produced the “Chronicles” cover for Manaka and whose own book “Rockin’ the Boat” (see Pacific Citizen, Oct. 9, 2020) photographically documented the same era, albeit with a different focus; Candice Ota, who designed and copy-edited “Chronicles”; “Buddhahead Trilogy” author Nick Nagatani for his guidance on self-publishing a book; and author Jamie Ford (“Hotel at the Corner of Bitter and Sweet”) for his advice.

Manaka said his real inspiration for writing “Chronicles,” however, came from his late uncle, Royal Louis “Louie” Manaka, a Nisei who during World War II served in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and died in December 2019.

It was at Louie Manaka’s celebration of life, which drew more than 500 people, that Harry Manaka related a story told to him by his uncle. While on leave and in uniform, he went to visit his family while they were incarcerated at Arizona’s Poston War Relocation Authority Center.

“On the way there, he stopped in Parker, Ariz., to get a haircut,” Manaka said. “He was told, ‘We don’t cut Jap hair here.’” Painful as it was, that was not an experience unique to Manaka’s uncle. But the incident did spark something in Harry, who thought to himself, “I sure would like to write some sort of tribute to Uncle Louie.”

“That’s how it started out. Then I thought, ‘I don’t know anything about that. But I do know about playing in bands and all that,’” he laughed.

Manaka credited Uncle Louie — and the Nisei in general — for that inspiration.

“The Sansei, we stand tall because we stand on the shoulders of the Nisei,” Manaka said of the sacrifices made by that generation.

Reelin’ in the Years

The eldest among the three sons and one daughter of the late Harry Manaka and Hanako (Nishida) Manaka (who is still thriving at 96), the younger Harry Manaka (referred to as “Junior” by his first piano teacher, Sue Joe Okabe) recalls beginning formal lessons around the third grade.

“I enjoyed playing, not necessarily for the music that was being taught to me. I used to like to try to bang out some of the rock ’n’ roll tunes on the piano, even though I wasn’t being taught that sort of music. I was being taught classical music,” Manaka said.

That attraction to pop, rock and soul music would lead to him a clash (which he relates in “Chronicles”) with Okabe, who, Manaka said, was “pretty renowned in the Japanese American community.” (Okabe died in 2002.)

Although Okabe sang jazz in addition to teaching piano, she wanted Manaka to stick with classical music. She told him he had the talent and skills to become a classical pianist — but the rock bug had bitten Junior, who one could say now had the rockin’ pneumonia and the boogie woogie flu.

“My mother, from across the street, would sometimes hear us yelling at each other, at the top of our lungs,” Manaka laughed. “Finally, one day she says, ‘Junior, you and I have come to a parting of the ways,’ and she sent me off to study under this piano teacher named Juan Donaldo Hernandez. He was a very famous classical pianist. But I continued to rebel.”

Like so many in his age range, Junior wanted to play rock. And he would as a keyboard player, first playing a Farfisa Combo Compact organ and later, as he relates in the book, his instrument of choice: the larger and heavier Hammond B3 organ.

Within a few years, Manaka would become a player in more than one of the many bands that served the Sansei dance party scene — and as much as “Chronicles of a Sansei Rocker” is a memoir of his days, it is also his recollections of the local L.A. bands (and venues) that influenced him, from Hispanic bands of the early 1960s to the bands comprised of Sansei and other Asian Americans that formed soon after.

Strike Up the Bands

In that regard, Manaka’s book may be the only one to list the names and members of groups such as Thee Chozen Few, Thee Essences (lots of bands using “Thee,” he notes) the Prophets, Carry On, Free Flight, Brown Rice, Long Time Comin’, Beaudry Express, the New Trend, Winfield Summit, Flashback, Small Fry and Fresh Air, but also some that only get name checks. (Benjo Blues Band, anyone?)

“Honestly, I do not know enough about these groups to be able to relate any background,” Manaka writes in the book. (Maybe “Chronicles” will inspire someone from one of those other bands to commit their recollections to the printed page.)

And, while Manaka clearly stated that the recollections are his, he did try to reach out to those he was able to, to corroborate — or not — some of those thoughts or get another perspective.

Were there rivalries between his band, Somethin’ Else, and the others?

“I always felt that there wasn’t a rivalry. My phrase used to always be ‘the rising tide lifts all boats.’ I thought we all made each other better,” Manaka said. “But in talking to people, they said some of the other band members were kind of jealous of our group because we always got to play last.

“We were always, I think, vying to be the featured band and talking to several of them (members of other bands), I thought, ‘Did that create any animosity?’ Most of them said it didn’t create any animosity toward me,” he continued. “It was just that they wanted the chance to play in the featured spot sometimes. I guess I didn’t realize that at the time.”

In his defense, Manaka noted that he didn’t pick who got to play last, but that it was the people who hired the different acts who made those decisions.

But no book about bands of this era with Sansei members would be complete with mentioning Hiroshima, which merits its own chapter.

Hiroshima landed a recording contract with the Arista label and crossed over to multiethnic jazz fusion fans and found success that continues to this day. Casual Hiroshima fans will no doubt find Manaka’s recollections of that band’s early days and its leader, Dan Kuramoto, of interest — perhaps serving as an inspiration for someone to write a book just about that band.

Can’t Forget the Motor City

While some of the aforementioned bands no doubt tried making original music, it was the live covers of the era’s hits that drew the Sansei audiences — and they wanted to hear soul and R&B, especially Motown. For Manaka, that was fine because he loved that music, as did his Sansei peers. But why?

“My theory is that a lot of Japanese Americans went to school with a diverse set of friends. I went to Long Beach Poly, and it was the only integrated high school in Long Beach,” said Manaka, noting that the city’s other high schools had no minority students. “I grew up with Black kids and Hispanic kids. I feel fortunate that that was the case because I was exposed to different kinds of music.

“I know that people who went to places like Dorsey and Washington and L.A. High School all grew up with Black kids, too,” he continued. “I’m not saying that that in and of itself created harmony or didn’t cause prejudice or anything because obviously it did. But at least it gave us exposure to other ethnic groups and for me, other music, and that’s how I came to like the Motown music.”

Manaka says he loved Smokey Robinson, the Temptations and the Four Tops — but due to his love of the sound of the Hammond B3, he grew to admire the Rascals, aka the Young Rascals, because of Felix Cavaliere and his B3 playing.

For Manaka, the Hammond B3 was the instrument for him. “It wasn’t a toy. It was definitely for serious musicians. I had to have that sound,” he said. To get that sound, he had to come up with $2,500, which at the time was a small fortune. But it was for a good reason.

“Our band was noted for playing all the Rascals music, exactly as they played it. That was intentional,” Manaka said. To do that, he said he and his bandmates slowed the records down so they could re-create the sounds and the harmonies note for note. “We wouldn’t do a new song until we had the intricacies of that particular song down pat.”

Somethin’ Else All Right

In addition to Manaka on keyboards, the most memorable version of that band, Somethin’ Else, comprised of bassist Bobby Flores, drummer Nick Urrutia, vocalist Royce “The Voice” Jones and on lead guitar, David Jingu.

In Jones, the band had a versatile singer whose ability to sing anything in any key meant they didn’t need to rearrange the hits to fit his range.

“He could do anything,” Manaka said. “He was a unique talent. I could see that from the moment I met him.”

In Jingu, they had a talent who was, as far as Manaka is concerned, the “premier lead guitarist of our era.”

For Manaka, Jingu was also a dear friend and future business partner.

Somethin’ Else consisted of (clockwise from top left) Hammond B3 player Harry Manaka, drummer Nick Urrutia, vocalist Royce Jones, guitarist David Jingu and bassist Bob Flores. (Photo: Courtesy of Harry Manaka)

A newly married Manaka and Jingu would not only play together in a band, in 1974, they became owners of a venue that allowed them to also have a steady gig, a place known as the Baby Lion, a bar and grill owned by Shoko and Dave Kanada near the USC campus with a diverse clientele that included Internal Revenue Service employees who were regulars.

Manaka relates how that came about after the demise of another band, Long Time Comin’, which had a successful but exhausting stint as the featured act in a Japanese nightclub in Tokyo.

With Manaka and Jingu playing together in a new incarnation of Somethin’ Else, they had a regular gig as the Baby Lion’s house band — and it became the go-to place for live music. When the Kanadas decided to sell and after the new prospective owners changed their minds, Jingu and Manaka stepped up and became the new owners — and it would be an education in how to run a business in the “real world” — again, with a little help from friends and Harry’s wife, Chris, who became adept at mixing drinks, despite being a teetotaler.

The Music Stops

Sadly, tragically, that era of Manaka’s life was actually a coda for his musical career and time operating a nightclub. Chris and Harry were getting burned out being in the restaurant and bar business. They reached an agreement with Jingu, who agreed to buy out their interest in the Baby Lion so that they could transition out of that business.

“I think my parents thought, ‘Well, he’s going to grow out of it and get a real job one of these days,’” he said.

That was accelerated unexpectedly by an incident that happened on Dec. 16, 1978.

On that date, Jingu was murdered.

It happened as he attempted to break up an altercation between one of the Baby Lion’s regular customers and a young man who was armed with a .357 magnum. Manaka was not there that night and still wonders if it would have turned out differently had he been there.

“I’ve beaten myself up over the years over that whole thing,” Manaka said. Maybe Manaka would have been killed that night. Or, maybe, since Manaka was known for being a diplomat and a peacemaker, he might have defused the incident. No one will ever know.

For Manaka, though, it was the day the music died. To say Jingu’s devastating end took the wind out of Manaka’s musical sails would be an understatement.

“I thought I would never play again,” he said. “How can I play if David will never be able to play again?”

The Baby Lion would, however, impart one gift that would alter the course of Manaka’s life. Thanks to that large IRS clientele, he learned of employment opportunities there. “I fell into the IRS very serendipitously,” Manaka said. It truly was time for somethin’ else.

Manaka applied for and landed a job with the IRS, and he worked there for 30 years. He went from being a music man to, alluding to the Beatles yet again, becoming the “Taxman.” The economics degree from UCLA didn’t hurt.

“I was one of the fortunate people to be able to compete and rise to what they call the senior executive service,” Manaka said. As such, he and Chris (and their family to be) would move about to different regions, including Washington, D.C., St. Louis and Honolulu. While in St. Louis in 1994, he became the assistant director.

“It was the first time they had had any minority in the position of being the executive or of having power over them,” he said. “I was like a novelty back there.”

For Gerald Ishibashi, who wrote the foreword for “Chronicles of a Sansei Rocker” and was himself in a band (Stonebridge) and continues to work in music as a concert promoter, the significance of his best friend’s book is that it transmits a cumulative experience for the Sansei.

“Every generation has its moment,” Ishibashi said. “For the Nisei, it was camp. It was there come-together moment.” Good or not, camp, was the experience common touchpoint for the Nisei.

“For the Sansei, especially in L.A., the common experience was those entertainment events, whatever the venue was. Some of them were in sororities, some of them were in fraternities, some went to UCLA, some went to USC, some played softball, some played basketball, some were bowlers. But the one common experience that Sansei in the L.A. basin had was going to those events.”

Indeed. Manaka said the first pressing of the book was 750 copies and that every day more orders come in, just from people who “heard it through the grapevine” that he had written this book — and every night he’s packaging more to take to the post office. Now he’s thinking about ordering more books to meet the demand.

If only there were recordings of Somethin’ Else to sell, too. Other than a jingle that was recorded for radio, Manaka knows of no recordings of which he is a part. It was a different time. No one had digital field recorders or iPhones to capture video and sound. Today’s tastes have changed. Now, not every neighborhood has its own band, since venues have disappeared since live bands have been supplanted by DJs, pop radio by digital playback and streaming.

It’s all just memories now — and those memories are kicking in hard, now that so many Sansei have reached retirement age. Manaka shared some excerpts of emails he’s received since the book came out.

- I received your package, unwrapped your book, cried when I saw the cover and sat down to read

- I did not put your book down until I finished. I loved your book, Harry. It reads like you just sat down to tell me your story.

- I’m kind of speechless and overwhelmed right now. Those of us who grew up in that era will love your book! I did. … I’ve never read a book from cover to cover in one sitting until now.

- Loved the book Harry. So much detail! Sad re: David though. I never knew the whole story. What a tragedy. I’m going to read it again this weekend just in case I missed anything.

From his home in Sammamish, Wash., Manaka is thoughtful, knowing he’s touched a nerve with his peers.

“The Japanese American community has been so good to me. I would like to, if I am so presumptuous to think that there are going to be proceeds from everything I’m doing, donate it back to either a nonprofit or a charity that is in line or suitable with what I’m planning.”

Although his days as a working musician are long past, Harry Manaka still plays the piano when the mood strikes. (Photo: Courtesy of Harry Manaka)

The Beatles had another Baby Boomer classic: “When I’m 64.” Manaka is nearly a decade past that mark, and for him, age brings perspective.

“To me, this is the best time of my life,” he reflected. “I’m having more fun now, especially that I’m reconnecting with so many people from my younger days.”

Will Manaka and some of these bands make a comeback? Could a reunion for some of these bands be in the works? Will they get back to where they once belonged?

Said Manaka: “We’ve started to create this new circle of people that I knew back in the day, and they are so enthusiastic about keeping it up. I would love to keep it up.”

“Chronicles of a Sansei Rocker” is for sale at SanseiRocker.com at $20 per copy, which includes shipping within the U.S.