Panel participants included (clockwise from top left) Shirley Ann Higuchi, Warren Furutani, moderator David Ono, Norman Mineta, Dale Minami and Mike Honda. (Photo: David Fujioka)

Panelists participate in several events to commemorate the

79th anniversary of the signing of Executive Order 9066.

By Ray Locker, Contributor

When members of the Sansei generation of Japanese Americans realized the scope of what their elders had endured during World War II, they reacted with a fervent activism born out of the anger of their discovery, a panel convened by San Jose’s Japanese American museum on Feb. 13 said.

“I got pissed off,” said Dale Minami, a San Francisco attorney who led the fight to overturn the wartime conviction of Fred Korematsu, the legendary protester of the Japanese American incarceration.

Minami was one of four members of the online discussion that was sponsored by the Japanese American Museum of San Jose along with author Shirley Ann Higuchi, chair of the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation; Democratic former California Assemblyman Warren Furutani; and former U.S. Rep. Mike Honda (D-Calif.).

Higuchi, Honda and Minami said their parents didn’t tell them much about their wartime incarceration, while Furutani said his father’s open discussion of his imprisonment in Rohwer, Ark., inspired his activism.

Furutani said he emulated himself after African American activist Malcolm X because he didn’t think the calmer civil disobedience efforts of people like Martin Luther King Jr. went far enough.

The panel was brought together as part of a series of discussions tied to Higuchi’s new book — “Setsuko’s Secret: Heart Mountain and the Legacy of the Japanese American Incarceration.” Higuchi wrote that she grew up in Ann Arbor, Mich., with no Japanese American friends or neighbors, and that it was only on her mother’s deathbed in 2005 that she realized Setsuko Higuchi’s commitment to building something at the Heart Mountain, Wyo., site where she had been incarcerated.

Honda was a baby when he and his family were forced from their homes south of Sacramento and sent to the Japanese American concentration camp at Amache, Colo. He was drawn to public service by the examples of Japanese American leaders such as Norman Mineta, a former Heart Mountain incarceree who became mayor of San Jose, a U.S. representative and a Cabinet Secretary under two presidents.

“The promises made to us weren’t the American dream, they were the American nightmare,” Minami said.

While a student at the University of California Berkeley School of Law, Minami read the decisions in the Japanese American incarceration cases involving Korematsu, Mitsuye Endo, Gordon Hirabayashi and Minoru Yasui. He saw through the thin legal reasoning in three unsuccessful challenges by Korematsu, Hirabayashi and Yasui and was determined to right those wrongs.

In 1982, he joined the legal team that was successfully able to get Korematsu’s original 1942 conviction thrown out.

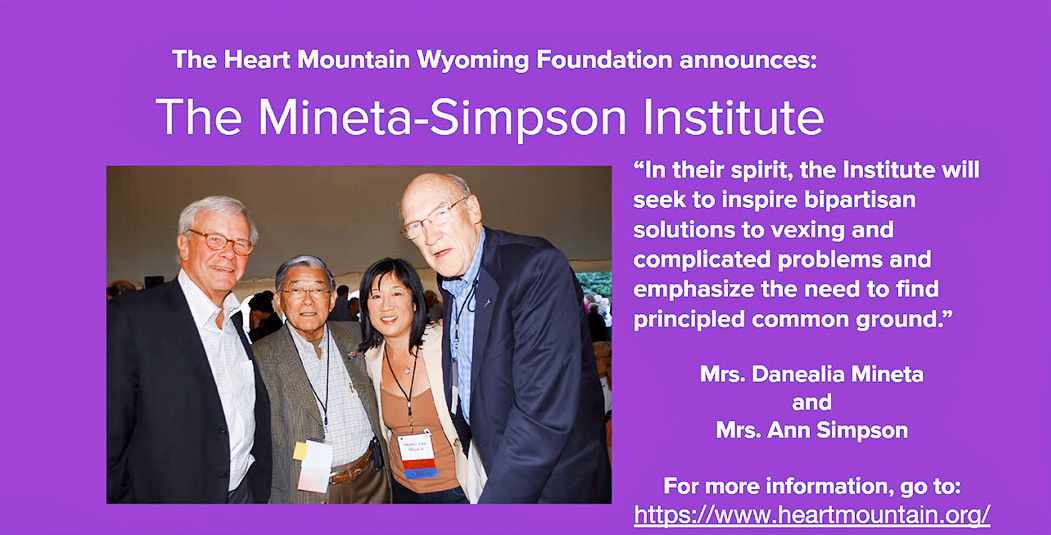

Heart Mountain’s newest project, the Mineta-Simpson Institute, will educate and feature programming on the lessons to be learned from the incarceration experience.

All of the panel said they believed Japanese Americans needed to unburden themselves of the multigenerational trauma associated with the incarceration and embrace who they really are, not the Model Minority myth foisted on them by Caucasian society.

While Furutani, Honda and Minami said they grew up in areas with many Japanese Americans, unlike Higuchi, they did not see Asians represented in the wider society at all.

The only Asian Honda saw on television, he said, was the character of Hop Sing, the Chinese immigrant cook on the series “Bonanza.”

Honda said he knew something was wrong and needed to change. “If you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem,” he said.

“The promises made to us weren’t the American dream, they were the American nightmare.”

— Dale Minami

The challenge facing the Japanese American community now, Furutani said, is that the next Nikkei generation is multiracial, which means the community must expand what it means to be Japanese American.

David Ono, the afternoon anchor for ABC7 news in Los Angeles, said it was remarkable how much of a “hellion” Furutani was during the 1960s, when he led movements to establish Asian American studies programs on California campuses and help start the pilgrimages to the Manzanar concentration camp.

Mineta spoke at the end of the panel and echoed the need for activism and that Japanese Americans had to remember that they had almost lost their citizenship rights during the war. He said he will always cherish being called an American citizen.

The program was organized by Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation Board Members Lia Nitake and Prentiss Uchida, who was incarcerated at Heart Mountain as a child.

Higuchi mentioned Heart Mountain’s newest project — the creation of the Mineta-Simpson Institute, which will be dedicated to the lives and careers of Mineta and former Sen. Alan Simpson, a Wyoming Republican who met Mineta while both were Boy Scouts in 1943.

The San Jose event was the first of many that week in February in which the panelists participated in memory of the 79th anniversary of the signing of Executive Order 9066.

Higuchi spoke with Dr. Rob Citino of the National WWII Museum in New Orleans about “Setsuko’s Secret” and the incarceration’s impact on the Japanese American community and the rest of the country.

She told Citino there was no better way to examine the systemic racism used against African Americans than HR 40, the House bill to create a commission to study potential reparations for Black Americans.

Higuchi cited the example set by Mineta and the late Sen. Daniel Inouye (D-Hawaii) in 1979, when they pushed for a commission to study the Japanese American incarceration. That led to the creation of the Commission on the Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, which conducted hearings that eventually led to the passage of the 1988 Civil Liberties Act.

That law apologized for the incarceration and paid each surviving incarceree $20,000.