“Facing the Mountain: The True Story of Japanese American Heroes in World War II,” is the new book by author Daniel James Brown, whose previous work was the bestseller “The Boys in the Boat: Nine Americans and Their Epic Quest for Gold at the 1936 Berlin Olympics.”

The bestselling author of ‘Boys in the Boat’ puts the spotlight on the 442nd in a new book.

By George Toshio Johnston, P.C. Senior Editor, Digital & Social Media

With the May 11 release of Daniel James Brown’s book “Facing the Mountain: The True Story of Japanese American Heroes in World War II,” as its subtitle states, it’s possible that the Japanese American experience on battlefields (and in courtrooms) of that era is finally about to be illuminated in a big, big way.

Author Daniel James Brown’s latest work is titled “Facing the Mountain.”

That’s because the bestselling author — whose 2013 book “The Boys in the Boat: Nine Americans and Their Epic Quest for Gold at the 1936 Berlin Olympics” was a career-making smash hit that turned the Seattle-based Brown into a brand-name superstar — has already generated news that “Facing the Mountain” might become a multipart series, with Hawaii-born Japanese American director Destin Daniel Cretton, helmer of the upcoming Marvel Cinematic Universe installment “Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings,” attached to direct.

But a series is in the future, and the future, as the world had to learn with the continuing, unforeseen global pandemic that began in 2020, doesn’t always go according to plan.

The book “Facing the Mountain” is here, now and new, and in the coming weeks and months, Brown and Densho Executive Director Tom Ikeda will be in the spotlight to discuss Brown’s 540-page book (ISBN 9780525557401), published by Viking with a suggested retail price of $30, that began when the two met in 2015 in Seattle, when they were among the honorees at the annual Mayor’s Arts Awards.

Densho Executive Director Tom Ikeda

Brown was there to receive one of the many accolades for “The Boys in the Boat,” while Ikeda was there to be honored for, at that time, Densho’s two-decades of technology-driven efforts to digitally preserve and make accessible Japanese American history, whether digitized analog community newspapers like Pacific Citizen or video interviews of Japanese American community members.

It proved to be a fortuitous and serendipitous meeting. And, it helped that Brown, who grew up in the San Francisco Bay area, already had some second-hand knowledge of the Japanese American experience because of his father, who sold wholesale florist supplies to flower shops and nurseries.

Brown told the Pacific Citizen that his father was usually even-keeled — but he could never forget one of the rare times when he saw his father get visibly angry and that was when he relayed what had happened to his many Japanese American friends and customers during the war.

“A lot of these folks came back to greenhouses that had been shattered and businesses that had been closed and land that had been taken out from under them,” Brown said. “You’d sort of have to know my father to appreciate how rare it was that he would get that angry. But it really stuck with me as a kid.”

Following the ceremony, Brown introduced himself to Ikeda after hearing him discuss Densho and its mission. Ikeda, meantime, told the Pacific Citizen that he was familiar with Brown’s work, having read and enjoyed “The Boys in the Boat.”

Later, Brown went to Densho.org and began listening to some of the oral histories and was drawn to what he had heard.

“They were stories about perseverance and resilience and ordinary people confronting difficult times and challenges and having to overcome them,” Brown said.

The seed that had been planted at the Mayor’s Arts Awards was sprouting — but it was still a long way from becoming a book.

“At that point, I don’t think it was really clear to him what exact story he was going to tell,” Ikeda said, “so I remember just sharing kind of a range of oral histories … and we would just have conversations back and forth, and he would say, ‘Oh, this is really interesting,’ and as he started getting more interested in the military service, I was feeding him stories both on the MIS as well as the 442 as well as the earlier 100th.”

Brown’s recollections dovetailed with Ikeda’s.

“The deeper I went, the more intrigued I became,” Brown said.

“I started talking with Tom, and he and I spent about a year going back and forth talking about different scenarios and different possibilities for how this might be developed into a book.

“The challenge that we had, as we talked back and forth,” Brown continued, “was what would the story be because we’re talking something finite in terms of the book. You can’t tell the whole story of the Japanese American experience.”

Still, it was progress. Brown’s publisher, meantime, was chomping at the bit for a follow to “The Boys in the Boat.” But were they really interested in a book that focused on the experiences of some Japanese Americans during WWII? Did it have the crossover appeal it needed to approach the success of “The Boys in the Boat”?

“They didn’t seem to blink. I was wondering how that would go myself, for some sort of obvious reasons. Frankly, I think they were just glad to get a manuscript in hand,” Brown chuckled. “It had been many, many years that I had not been handing them anything. Actually, when they read the proposal for the book and sample chapters, they were all in right away.”

But before Brown could turn in a final draft last year, he needed to do the research. While Densho, the Go For Broke National Education Center and the Japanese American National Museum all were helpful resources, Brown also visited Hawaii and Europe, where the 442 fought, to do even more research. As welcome as it might seem to have to go to Hawaii and Italy to conduct research, for Brown, it was a necessity.

Contrasting what he recalled learning in school about the experiences Asians have had in the U.S., Brown said he thought he was “pretty well acquainted” with the Asian American and Japanese American communities.

“But, I will tell you, researching the book was in many ways a revelation to me,” Brown said. “I mean, I really dove deep into the history of the Chinese Exclusion Act and these various restrictive laws. I dove into the violence against Chinese immigrants, starting with the Gold Rush in the 1850s, the Yellow Peril years and all that. I’m an educated guy, and I had known all that existed, but it really brought it home to me in a way that it hadn’t before.”

Brown also noted that working on the book overlapped with the Trump administration.

Watch Densho’s “Facing the Mountain” book launch video here.

“I was reading about all these families trying to make their way in America at the same time the ‘Muslim ban’ thing was going on and then doing a deep dive into the concentration camps at the same time the administration was breaking families up and incarcerating families,” he said. “My book is not overtly political, but it certainly was fueled by all that stuff that was going on.

“The process of researching the book deepened and sharpened my awareness in a way that surprised me because I thought I had known the story pretty well, which I suspect is true of a lot of non-Japanese Americans,” Brown continued. “I think that they feel that they know the story better than they really do.”

Related to that, Brown said he was “kind of stunned” when he was talking with some of the people associated with the book’s publisher at “how little they knew about the story.”

“I think it’s partly an East Coast/West Coast thing,” Brown said. “I was absolutely flabbergasted, actually, at how little they knew about what had happened. I think most of them had some vague idea that Japanese Americans were incarcerated during the war, but boy, that was as far as their understanding went. I don’t know why it hasn’t penetrated more. I don’t really know the answer.

“My book isn’t going to change the world here, but one of the reasons I wanted to write this book was my previous book was very successful, so I knew I’d have a big platform for this book. … When I started digging into these stories and meeting these family members, I really thought I wanted to use my heightened platform for making the story better known, particularly outside the Japanese American community, obviously.”

One of the obstacles Brown faced, too, was that so many of the people whose stories had been preserved had died. But he was able to spend extensive time with one of the four principal “characters” he ultimately settled on to tell the story, Fred Shiosaki of Seattle. Shiosaki was a member of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team’s K Co., which was involved in the Rescue of the Lost Battalion.

“Fred fit neatly into the narrative I was trying to create because he was in the right places at the right time,” Brown said. But their relationship ended, however, when Shiosaki died at 96 on April 10.

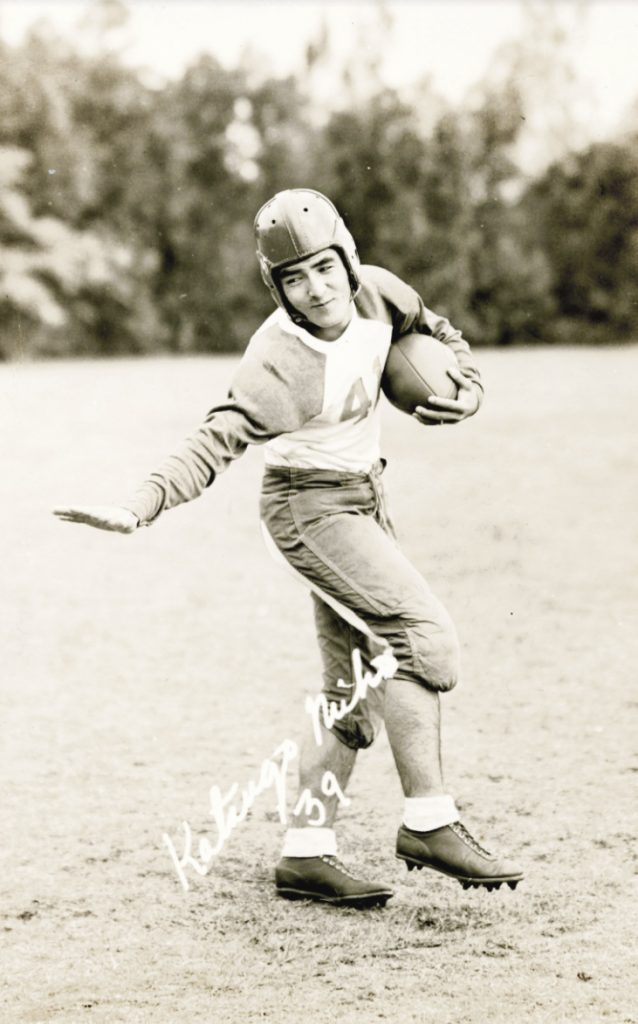

Kats Miho at Maui High (Photo: Katsugo Miho Family Estate)

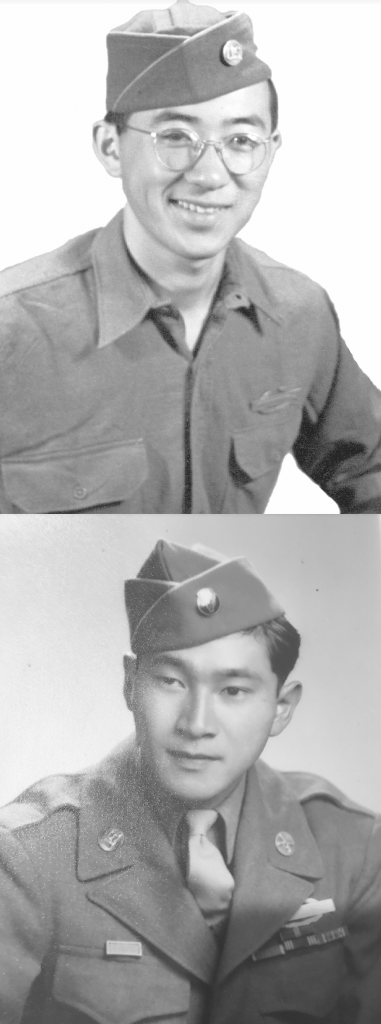

Top: Pvt. Fred Shiosaki (Photo: Shiosaki Family Collection) Below: Pvt. Rudy Tokiwa (Photo: Courtesy of the Tokiwa Family Collection)

The other men who have prominent roles in “Facing the Mountain” are Kats Miho, who was born in Hawaii on the island of Maui, and from the mainland like Shiosaki, Rudy Tokiwa and Gordon Hirabayashi, who wasn’t a soldier but someone who fought using the legal system against the injustice visited upon Japanese Americans by the federal government.

Gordon Hirabayashi (photo: University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, SOC9328)

For Ikeda and Densho, working with Brown is just the latest part of the journey that began 25 years ago.

“Our mission is to preserve and share the stories of the World War II Japanese American incarceration to promote justice and equity today,” said Ikeda. “So, to have someone like Dan interested in the stories and consider writing a book really was, I think, in terms of what we were thinking, a way to share the story.”

Over the years, Ikeda said he has met many authors and filmmakers who were interested in the Densho repository. But there was something about Brown that stood out — how closely he listened.

“It didn’t seem like he was coming in with an agenda,” Ikeda said. “He was very curious. The thing that I noticed and appreciated was he listened to some thoughts and then he did the work. He actually went to our archive and learned how to use it.”

Before long, thanks to the research Brown had done, he soon learned and knew “things that I didn’t know,” Ikeda said. “It was, actually, at some point, a really interesting relationship in terms of sharing information.”

That relationship no doubt will continue to evolve in the coming weeks with the rollout of publicity for “Facing the Mountain.”

For Brown, having completed the book means he is still in a postcompletion refractory period. He did allow that he may try writing fiction for book No. 5.

Professionally, Brown is, at nearly 70, in a good place, with writing books for a living his third career; his first career was teaching English at the college level, which was followed by working as a technical writer and editor.

“Twenty years ago now, I just sort of on the side started writing a book about a piece of my family history.”

That was the basis for “Under a Flaming Sky: The Great Hinckley Firestorm of 1894,” about a deadly forest fire in Minnesota that killed 350 people, one of whom was his great-grandfather.

The book did reasonably well, and Brown secured a contract for a second book, “The Indifferent Stars Above: The Harrowing Saga of the Donner Party Bride.”

And, of course, there is Hollywood, what with “Facing the Mountain” on its way to becoming adapted for the screen and “The Boys in the Boat” looking ready to be directed by George Clooney.

But, as noted, that is all in the future. The book is now and Brown is hopeful that he achieved the book’s purpose — or as he put it: “I think contextualizing and putting this whole thing into human terms, terms that anybody can identify with, what it’s like to suddenly have your home taken away from you, and your business and your livelihood.

“That’s what I’m trying to do with the book — get people to open their hearts and look through a different set of eyes than they may have in the past and consider what it’s like to have these series of traumas inflicted on you and reflect on what that means with where we are today.”

Prologue

(Following is the prologue, written by Densho Executive Director Tom Ikeda, for Daniel James Brown’s “Facing the Mountain.” It has been reprinted with permission courtesy of its publisher, Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House. Copyright © 2021 by Daniel James Brown.)

‘We made the sacrifices. It was a sense of “Hey, I earned this. It’s not that you owe me. It’s this — that we have earned this.”’

— Fred Shiosaki

By Tom Ikeda, Densho Executive Director

One of the many pleasures of writing a book like this is meeting the extraordinary people who have lived the story you are telling. Usually, you meet them only virtually, through the letters or diaries or video recordings they have left behind. Occasionally, if you are lucky, you get to meet them in person.

Such was the case on a typically splendid Hawaiian afternoon in 2018 when my friend Mariko Miho ushered me into the Maple Garden Restaurant in Honolulu’s McCully-Mo‘ili‘ili neighborhood. The place was loud with the clattering of dishes and lush with warm aromas arising from a buffet arrayed along one wall. Most of the people lined up at the buffet were there for the midweek, midday senior discount. We were there for the company.

Such was the case on a typically splendid Hawaiian afternoon in 2018 when my friend Mariko Miho ushered me into the Maple Garden Restaurant in Honolulu’s McCully-Mo‘ili‘ili neighborhood. The place was loud with the clattering of dishes and lush with warm aromas arising from a buffet arrayed along one wall. Most of the people lined up at the buffet were there for the midweek, midday senior discount. We were there for the company.

Mariko led me to the back of the restaurant where half a dozen white-haired gentlemen, all in their nineties, were sitting at two large round tables, surrounded by their wives and sons and daughters. Mariko introduced me. Everyone smiled and waved a bit shyly and then resumed their conversations. Mariko seated me next to two of the gentlemen and introduced them to me as Roy Fujii and Flint Yonashiro. They were veterans of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT). During World War II, the regiment had fought the fascist powers in Europe so valiantly that they had emerged from the war as one of the most decorated units in American history. Roy and Flint had known and cared for each other for at least seventy-five years. They had fought together, lost friends together, bled together, been through hell together.

Soon, they were both regaling me with stories, and I was flinging questions at them. Roy patiently explained how to adjust the elevation settings on a 105-millimeter howitzer. They both talked about the terrifying sound of incoming artillery shells, about handing out candy bars to starving children in Italy, about swimming in the Mediterranean, and about picking their way through deadly minefields in Germany. I pulled out some maps, and soon both men were hunched over them, eagerly comparing notes, pointing out features of some terrain in France—mountains they had climbed, river crossings where friends had died. We talked for an hour or more, and through it all they were both so bright-eyed and clearheaded and vibrantly alive that you might have thought them twentysomething rather than ninetysomething. It was easy to see the eager, audacious, good-hearted young men they had once been.

When lunch was over and the veterans began to push their chairs away from the tables, family members scrambled for walkers and canes. Daughters who were themselves in their sixties or seventies rushed to help their fathers stand up. Sons cleared aisles for wheelchairs. When Roy Fujii rose to stand, he wobbled just a bit. A chair stood between him and the door, and it wasn’t clear that he saw it. Faster than I could have, ninety-four- year-old Flint Yonashiro sprang to his feet, sprinted around the table, pushed the chair out of the way, steadied Roy, and handed him his cane.

It was a small thing, but I’ll never forget it. It summed up in a gesture everything I have learned about not only those half a dozen men but thousands more just like them. For three-quarters of a century, all across the country, they have been coming together—at luncheons and dinners and lū‘au, in homes and restaurants and veterans’ halls—needing to be in one another’s presence again, needing to show again how much they love one another, needing to take care of each other, as brothers do. As they left the restaurant that afternoon, strangers made way for them, and a hushed reverence washed over the room. All of us knew that they would not be with us much longer, and all of us wished that were not so. And that is why I have set out here—with a great deal of help from some of them, and from their sons and daughters and friends and compatriots— to tell you their remarkable story as best I can.

Some came from small towns, some from big cities. Some hailed from family farms in the American West, some from vast pineapple and sugarcane plantations in Hawai‘i. By and large, they had grown up like other American boys, playing baseball and football and going to Saturday afternoon matinees. They performed in marching bands on the Fourth of July, went to county fairs, ate burgers and fries, messed around under the hoods of cars, and listened to swing tunes on the radio. They made plans to go to college or work in the family business or run the farm someday. They eyed pretty girls walking down school corridors clutching books to their chests, making their way to class. They studied American history and English literature, took PE and shop classes, looked forward to their weekends. And as the holiday season approached in 1941, it seemed as if the whole world lay before them.

But within hours of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, all that changed. Within days, the FBI was banging on their doors, searching their homes, hauling their fathers away to undisclosed locations. Within weeks, many of them would watch as their immigrant parents were forced to sell their homes for pennies on the dollar and shutter businesses that they had spent decades building. Within months, tens of thousands of them or their family members would be living in barracks behind barbed wire or have family members who were.

For all their essential Americanness, the traumatic events of that December brought back into focus something they had always known: their place in American society remained tenuous. Millions of their country- men regarded them with an unfettered animosity born of decades of virulent anti-Asian rhetoric spewing forth from the press and from the mouths of politicians. Local ordinances regulated where they could and could not live. Labor unions routinely barred them from employment in many industries. Proprietors of businesses could, at will, ban them from entering their premises. Public facilities were sometimes closed to them. State laws prohibited their parents from owning real estate. In many states they were not free to marry across racial lines. Their national government prohibited their parents from becoming citizens.

Lt. Col. Pursall and President Truman review the 442nd. (Photo: Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration)

And they knew this, too: their lives, their very identities, were inevitably bound to their roots. The values that their parents had bestowed on them—the manner in which they approached others, the standards by which they measured success, the obligations they felt, the respect they owed to their elders, the traditions they celebrated, and a multitude of other facets of their individual and collective identities—were not things they could or would willingly cast aside. They were, in fact, things they cherished.

Because many of them had relatives living in Japan, they had seen the storm clouds growing over the Pacific long before most other Americans had. And they knew immediately on that first Sunday in December 1941 that straddling two worlds now suddenly at war would challenge them in ways that would shake the foundations of their lives.

For those young men there was no obvious path forward, no simple right way or wrong way to proceed with their lives. Some of them would launch campaigns of conscientious resistance to the deprivation of their constitutional rights. Others—thousands of them—would serve, and some would die, on the battlefields of Europe, striving to prove their loyalty to their country. Scores of their mothers would dissolve

into tears as they saw grim-faced officers coming in past barbed-wire fencing bearing shattering news.

But by the end of their lives almost all of them—whether they fought in courtrooms or in foxholes—would be counted American heroes.

At its heart, this is the story of those young men—some of the bravest Americans who have ever lived, the Nisei warriors of World War II, and how they, through their actions, laid bare for all the world to see what exactly it means to be an American. But it’s also the story of their immigrant parents, the Issei, who like other immigrants before them— whether they came from Ireland or Italy, from North Africa or Latin America—faced suspicion and prejudice from the moment they arrived in America. It’s the story of how they set out to win their place in American society, working at menial jobs from dawn to dusk, quietly enduring discrimination and racial epithets, struggling to learn the language, building businesses, growing crops, knitting together families, nurturing their children, creating homes. It’s the story of wives and mothers and sisters who kept families together under extreme conditions. It’s the story of the first Americans since the Cherokee in 1838 to face wholesale forced removal from their homes, deprivation of their livelihoods, and mass incarceration.

But in the end it’s not a story of victims. Rather, it’s a story of victors, of people striving, resisting, rising up, standing on principle, laying down their lives, enduring, and prevailing. It celebrates some young Americans who decided they had no choice but to do what their sense of honor and loyalty told them was right, to cultivate their best selves, to embrace the demands of conscience, to leave their homes and families and sally forth into the fray, to confront and to conquer the mountain of troubles that lay suddenly in their paths.

[Editor’s note: The Pacific Citizen will have a drawing to give away one copy of “Facing the Mountain: The True Story of Japanese American Heroes in World War II” to a Pacific Citizen reader. Mail an envelope to: Pacific Citizen, ATTN: Facing the Mountain Book Drawing, 123 Astronaut Ellison S. Onizuka St., Ste. 313, Los Angeles, CA 90012. Letters must be postmarked by June 4, 2021. The winner of the drawing is asked to promise to write a letter to the editor giving his/her thoughts on the book.]