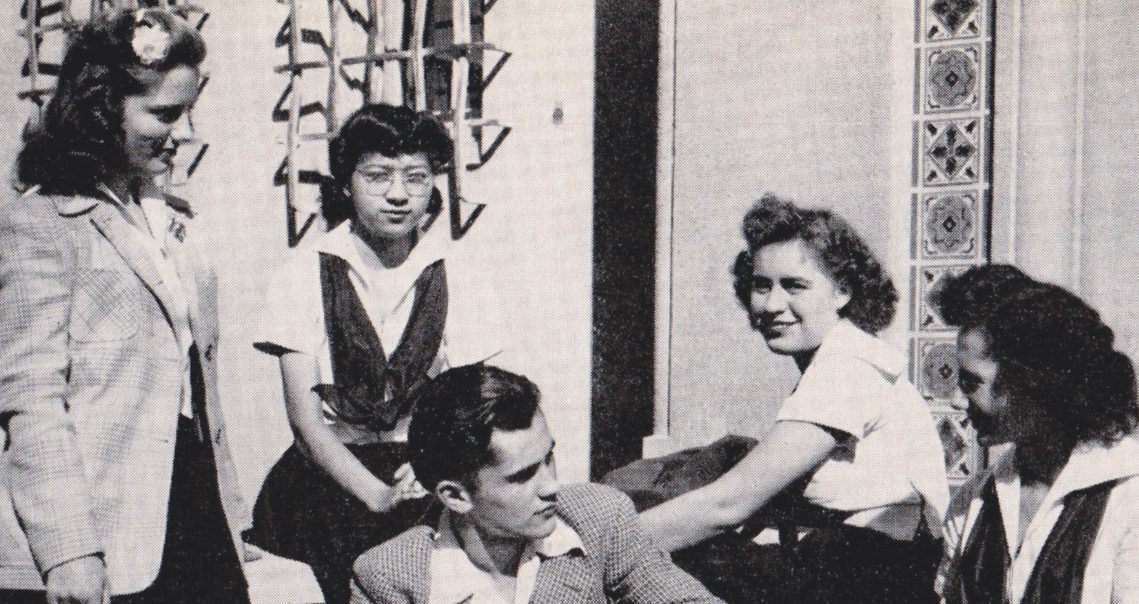

Serving as Mt. Diablo’s Class of 1942 student body officers were, from left, Elva Mae Peters (chair of entertainment), Sumiko Watanabe (treasurer), Bonnie Colvard (secretary), Bob Levada (president) and Virginia Sanders (vice president) (Photo: Courtesy of Scott Ananos)

May and June are the months when high school and college students graduate en masse. At many schools, 2022 was the first time since 2019 that in-person graduations were allowed, due to safety practices to limit the spread of Covid-19. This year was also special for another reason: Some Nisei students who were unable to complete their high school or college educations 80 years earlier in 1942 — most of them now deceased — were able to have their descendants receive belated honorary diplomas.

Mt. Diablo High’s students honor their Nisei predecessors.

By George Toshio Johnston, Senior Editor

Among today’s many hot-button issues, both social media use (and misuse) and the teaching of ethnic studies in high school can get as heated and stifling as the inside of a parked car at noon in late June.

Nevertheless, it was a Facebook post that was read by an ethnic studies teacher in Concord, Calif., that resulted in an emotional and reconciliatory convergence on the evening of May 24. (Read related story here.)

Mt. Diablo High School history and ethnic studies teacher Laura Valdez reviews the school’s 1942 yearbook. (Photo: Courtesy of Theresa Harrington)

That was when nearly 40 now-deceased or now-elderly former Mt. Diablo High School students were finally recognized, eight decades after being denied the opportunity to take part in a vital rite of passage woven into the fabric of American society: striding across a stage before one’s peers and family, wearing a flowing robe while crowned with a mortarboard cap with a tassel to accept a high school diploma.

Those freshman, sophomores, juniors and seniors who attended Mt. Diablo High School in 1942 who were denied the opportunity to get their diplomas that year — and the immediate years afterward — were the school’s students of Japanese ancestry.

America’s entry into World War II after Japan’s Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor and President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Feb. 19, 1942, Executive Order 9066 saw to it that by the time the 1941-42 school year ended, those Japanese American students and their families were gone, removed to far-flung concentration camps.

Youthful Perspective

When Anahí Nava Flores, 16, who will be a junior in the fall at MDHS, learned in Laura Valdez’s ethnic studies class about what had happened 80 years earlier to her predecessors who were Nisei, she told the Pacific Citizen of her reaction to this knowledge.

“It did not shock me at all, learning that this was going on in the U.S., here in America,” said Nava Flores, who is the daughter of Mexican immigrants. “We can see throughout history how many races and many communities have faced xenophobia and racial discrimination and prejudice.”

Her reaction was different, however, when she found out what had happened eight decades prior was so close to home. “When I learned that this happened here in Concord, here in California, it really shocked me,” Nava Flores, said, adding, “They did everything. They took the courses, they did the learning, they passed their classes … and because of xenophobia and racial discrimination, they were forced to withdraw from this school and be placed into an incarceration camp.”

Teaching the Teachers

It was also a learning experience for her teacher. “It’s been very eye-opening for myself and for my students,” said Valdez, who is white. “This is my first year teaching ethnic studies. … I’ve gotten a lot out of it. I hope the kids have, too.”

As a teacher and someone who grew up in the Concord area, Valdez’s perspective stretches back further than that of her students. But thinking back to when she was in high school, she says she didn’t learn anything about the experiences of Japanese Americans during WWII. “I grew up in this district, as well, and I don’t recall learning it,” she said. “I remember learning about the Holocaust and different parts of World War II, but I don’t remember really learning about it.

“In fact, my ex-husband was in the Air Force, and we were stationed in Arkansas, and I think I learned about it because I passed by one of the camps in Jerome.”

Seeing Is Believing

In the 80 years since 1942, the racial and ethnic makeup of Mt. Diablo High School’s student body has changed. Back then, most of the students were white Americans, and the largest nonwhite group was Japanese American. In 2022, the students are more than 90 percent Hispanic American, with some students living with parents who may be undocumented.

For those and other reasons, Valdez, who also teaches history at the school, believes that her students can identify with what happened to their Nisei forerunners, since they are aware of issues surrounding immigration, deportations and the like. “I think that there’s a lot of parallels in some ways,” she told the Pacific Citizen.

Mt. Diablo High School’s 1942 yearbook (Photo: Courtesy of Theresa Harrington)

For fellow history teacher and yearbook adviser Scott Ananos, the impact of EO 9066 is as clear as the difference between the MDHS yearbooks of 1942 and ’43. In 1942 and before, though a minority presence, Japanese Americans, whether in class portraits or photos of student officers, sports teams or other activities, are visible and apparent.

So, too, is the complete absence of Japanese faces in 1943 and after.

“It’s something you know about, but when you see it, that has such a huge impact on everyone,” said Ananos. Even among older staff members, one might assume to not necessarily align with the idea of presenting honorary diplomas to the Nisei students who didn’t get their diplomas from MDHS, the difference between the 1942 and ’43 yearbooks made a huge difference. “The visual really led them to jumping in and assisting us right away,” he added.

Social Media Action

According to MDHS Class of 1958 alumna Kimiyo Tahira Dowell, what led to her school’s 2022 recognition of Nisei students was a Facebook post.

In the private Facebook group for MDHS alumni was a 2021 post about the rise in anti-Asian violence. A retired attorney, Dowell remembered that in 2003, California passed AB 781, which allowed state high schools to retroactively grant diplomas to Japanese Americans who were incarcerated during WWII.

She also knew that in the intervening years, her alma mater had not taken up the issue of recognizing Nisei students who were denied the chance to get their diplomas the way other schools did. Could this belated recognition be an antidote to the surge in anti-Asian violence, serve as an example of restorative justice and teach the younger generation something about U.S. history, albeit one of the sadder aspects?

“The response was fabulous. They said, ‘Let’s do it, let’s do it!’” Dowell told the Pacific Citizen. When Valdez, who was also a member of that Facebook group, saw Dowell’s post and the positive responses, she knew she had to reach out to Dowell. Soon, the two began communicating.

Making the Case

As Dowell began using information provided in the school’s 1942 yearbook from Ananos to assist with her internet research to track down those Nisei MDHS students of 1942 and the immediate years thereafter, Valdez gave her students an assignment: Write a business letter and email it to a school board member or the principal to ask for approval from the school board to grant retroactive diplomas.

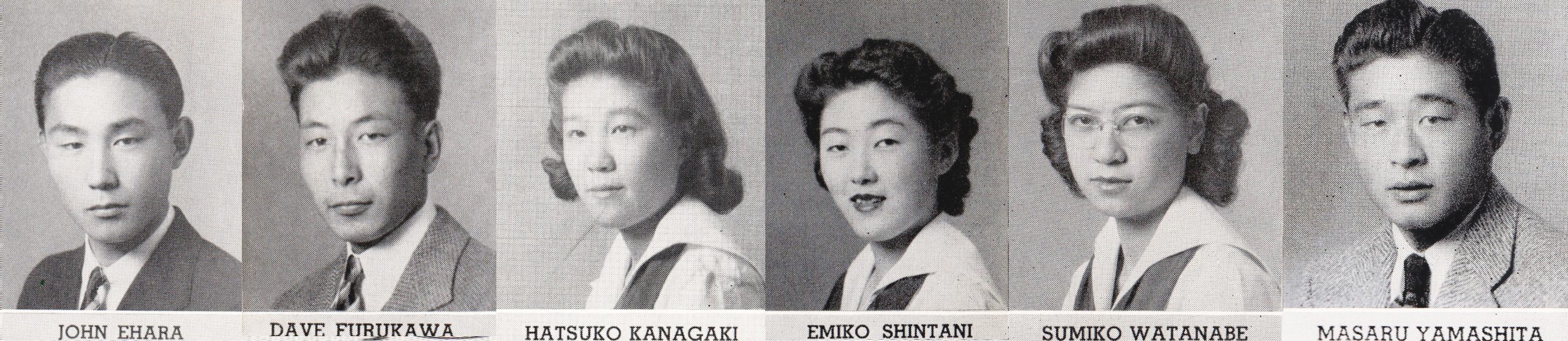

Above: Mt. Diablo’s Class of 1942 Nisei seniors: John Ehara, Sam Furukawa, Hatsuko Kanagaki, Emiko Shintani, Sumiko S. Watanabe and Masaru Yamashita. Underclassmen were Isao Daniel Fukuchi, Fumiko June Fukuchi, Satoshi Fukuchi, Dave Furukawa, Susie Furukawa, Irene Yoshie Hara, Yayoi Rose Hara, May Ann Hara, Minoru Ben Ikeda, Natsu Ikeda, Kazuyoshi Kaida, Tatsuki “Tats” Kanada, Alice S. Kawauchi, George Kusaba, Shigeno Jack Kusaba, Fannie Satchiko Matsuda, Hitoshi Murata, Matsukio “Mats” Murata, Shigeji Nakanishi, Chizuko Catheran Nakatani, Yuriko Nakatani, Tohoru Tom Nakatani, Joey Y. Noma, Yoshie Lillian Okamoto, Manabu B. Sano, Hiroshi George Sano, George Y. Tamori, Masateru M. Terada, Kikue T. Terazawa, Hiroshi Tsuji, Hirotsugu Jim Tsuji, Misako Watanabe and Takashi “Tak” Yasuda

“We needed some student voices behind it to get it done,” said Valdez. “So, I really started actively teaching and recruiting the ethnic studies students to write letters, and they just started flooding the inboxes of all of the board members.”

Adding to the effort, Dowell, Valdez and two seniors, Arshpreet Garcha and Evelin Suarez Martinez, attended the Mt. Diablo Unified School District’s March 23 board meeting to advocate for issuing retroactive diplomas to the Nisei alumni from 80 years before.

From left: Kimi Tahira Dowell, students Arshpreet Garcha and Evelin Suarez Martinez and teacher Laura Valdez (Photo: Theresa Harrington)

All five board members and the superintendent approved the request unanimously. The stage was set to recognize those Nisei who attended MDHS in 1942 with honorary diplomas on May 24.

The Kanada Brothers

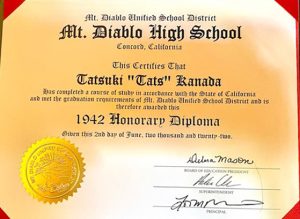

For siblings Gordon Kanada and Karen Leong, the recognition for their uncle, Tatsuki “Tats” Kanada — aka Uncle Tuffy — was special in many ways, allowing that getting the diploma was “bittersweet” and a form of “academic justice” for their uncle, who died in 2007.

For siblings Gordon Kanada and Karen Leong, the recognition for their uncle, Tatsuki “Tats” Kanada — aka Uncle Tuffy — was special in many ways, allowing that getting the diploma was “bittersweet” and a form of “academic justice” for their uncle, who died in 2007.

“I was overjoyed,” said Gordon Kanada. “Even though it took so long, it’s nice to be recognized.”

Tats Kanada was one of the five Kanada brothers; they also had a sister, Aki. According to Gordon Kanada, Tats was a junior in 1942 and thus didn’t graduate from MDHS; he and his family members were forcibly removed to the Gila River WRA Center in Arizona.

The eldest brother was Frank Kanada, father of Gordon and Karen. His four younger brothers — Harry, George, Tatsuki and James — all served in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. James, the youngest, however, did not come home; he was killed in action on April 5, 1945. It was a devastating blow to his surviving family.

Looking Ahead, Looking Back

Gayle Boesch displays the diploma of Sumiko Watanabe (Photo: Courtesy of Theresa Harrington)

For the MDHS Class of 2022 — and the honorary members of the Class of 2022, those Nisei from 80 years ago — the ceremonies have been completed and the well-earned diplomas distributed.

According to Valdez, however, there is still another yet-to-come project related to the Nisei students. “My class of ethnic studies kids for next year really want to put together a permanent memorial on campus,” she said. What form that memorial will ultimately take will be determined as the next school year progresses.

Wrapping up the very special 2022 MDHS graduation ceremony, Ananos said, “The moment that this all came together for me was at graduation, when Kimi read the names of all the students who were forced to leave the schools, and our student body gave her a standing ovation. And she was moved to tears.

“I think that it is so important that these moments are recognized and remembered, and the hardships realized by all of us. It’s not just one of those history things. It’s just a humanity thing, where people feel like they’re part of the community again. … It was a really cathartic and positive moment.”

(Editor’s note: To view the MDHS 2022 graduation ceremony, visit youtu.be/-NSutMqtQbE. To view the March 23 MDUSD board meeting, visit vimeo.com/691620554.)

Eighty years after being dropped from USC, Ted Matsushima gets his diploma.

After Vincent Oda received his April 15 issue of the Pacific Citizen in the mail and read its cover story, the Syracuse, Utah, resident thought something was amiss.

The article, about the University of Southern California’s Asian Pacific Alumni Assn.’s annual scholarship gala, contained a list of 35 Japanese American students who, in 1942, were dismissed from the university because of their ancestry after the U.S. declared war on Japan when it attacked Pearl Harbor weeks earlier.

As a result, those young people were unable to complete their educations at USC. Over the ensuing years, there was a realization that an injustice had happened to them, and that something should be done to heal it.

But USC had an ironclad policy: No posthumous diplomas. But that was before Carol Folt became the university’s president in 2019. Folt decided that it was time to make a new policy, and she was the person with the authority to do it.

So it was that at the April 1 event, USC broke its precedent and presented honorary diplomas eight decades later to the families of those Nisei whose college educations were disrupted by WWII.

When Oda read the P.C.’s article and the list of names, though, he thought to himself that one name seemed to be missing. Didn’t Uncle Ted, of Ogden, Utah, attend USC during that time? He definitely remembered when his uncle once gave him a USC sweatshirt after returning from a trip to California.

There was one way to confirm: Text his cousin, Louise Lund of San Francisco, and ask whether her father, Theodore Matsushima, who died at 85 on Aug. 31, 2007, did in fact attend USC at that time and if so, find out if he, too, should have received one of those honorary diplomas.

Who Was Ted Matsushima?

As a scholar and an athlete, in this 1940 photo from the Narbonne High School yearbook, Ted Matsushima (pictured at far left) served as co- caption of his varsity football team. (Photo: Chris Lund)

Ted Matsushima was the son of Fusaé and Sukito Matsushima. His Issei parents also raised his two younger sisters, Edith and Ruth, mother of Vince Oda.

By the time he was in high school, Ted Matsushima had become one of those rare boys who exceled at sports and academics: He was not only a co-captain of the football team, but also was the valedictorian of his graduating class at Nathaniel Narbonne High School in Los Angeles.

Oda would find confirmation from cousin Louise that her father, Theodore Matsushima, had indeed attended USC — on a full scholarship, no less.

Neither she nor her husband, Chris, however, had any inkling that USC had been searching for Nisei Trojans denied the opportunity to complete their degrees.

Had it not been for her cousin, Vince — and his subscription to the Pacific Citizen, which he still receives in the name of his deceased father, 442nd Regimental Combat Team vet Jimi Oda (whose life was saved by Medal of Honor recipient Sadao Munemori) — Louise might never have known that her father was among those eligible for an honorary degree from USC.

A Change in Direction

Young Ted Matsushima, by anyone’s reckoning, was destined for success, with a trajectory toward distinction in any field he wished to pursue all but preordained.

For Theodore Matsushima, however, and thousands of Japanese Americans living on the Pacific Coast of all ages, the events of Dec. 7, 1941, and Feb. 19, 1942 — Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor and President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, respectively — derailed all manner of plans, aspirations, dreams and desires.

After Ted’s father was taken in for questioning by government authorities and released, the elder Matsushima decided that his family would decamp for northern Utah to work on a farm, allowing the Matsushima family to avoid being incarcerated in one of the 10 War Relocation Authority Centers that would confine more than 120,000 ethnic Japanese living in America, U.S. citizens and legal resident aliens alike.

Life Goes On

Ted Matsushima in 1981 (Photo: Chris Lund)

Although graduating from USC would not happen for him, Ted Matsushima’s life was not ruined — far from it.

He served his nation as a member of the Army’s Military Intelligence Service. He met his future wife, Ruth Oda, in Utah, and together they raised four kids — Louise, Milton, Brian and Joseph. He also found work as a civilian at Hill Air Force Base in Utah, utilizing his knowledge of chemistry.

“I always remember him to be very, very smart,” Oda recalled of his uncle, who in his mind’s eye always seemed to be smoking a pipe or cigar.

According to Louise Lund, while she remembers that he did take a correspondence course to study law, her father never did return to a college campus to formally get a degree. That door had closed.

But once she and her husband, Chris, had learned that USC had conferred honorary diplomas to descendants of Nisei alumni whose college educations had been interrupted, they contacted Grace Shiba, the executive director of USC’S Asian Pacific Alumni Assn., to see if Ted Matsushima was eligible to receive one of the diplomas other Nisei Trojans received on April 1.

The Route Back to USC

According to Shiba, she asked the Lunds to complete an online form (alumni.usc.edu/apaa/nisei/) that the registrar’s office could then process. “Once they were able to locate the student’s records, it was approved and confirmed that he was one of our Nisei students,” Shiba told the Pacific Citizen.

As it turned out, the turnaround time was extraordinarily quick, since USC had already done some preliminary research on Matsushima. The query by the Lunds would complete and expedite the process.

Theodore “Ted” Matsushima’s daughter, Louise Lund, and her husband, Chris, hold up her father’s honorary diploma from USC, which the university finally awarded 80 years later. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Louise Lund gives the “Fight On” gesture in front of USC’s famous Tommy Trojan statue on the university’s campus. (Photo: Chris Lund)

On May 13, the Lunds, who had already received Theodore Matsushima’s diploma in the mail, were present for the university’s 2022 commencement ceremony — and his formal welcome back to the USC community.

The Matsushima family’s “golden child,” as Chris Lund called his father-in-law, had finally found a sort of posthumous completion of his youthful goal: earning a diploma from the University of Southern California.

“At first, I thought it was too little, too late. And then I thought about how it affected our family. I feel like it’s probably a good thing,” Louise Lund said following the May 13 ceremony.

“Even though I have mixed feelings, I think they’re recognizing that an injustice was done. So, that helps me kind of think about my dad just walking on the campus and feeling what he felt.”

At USC, meantime, the quest to find more Nisei Trojans whose lives were also interrupted continues, according to Shiba.

“We are going to go through a thorough research on the internet to find the lost families. This project isn’t over yet.”