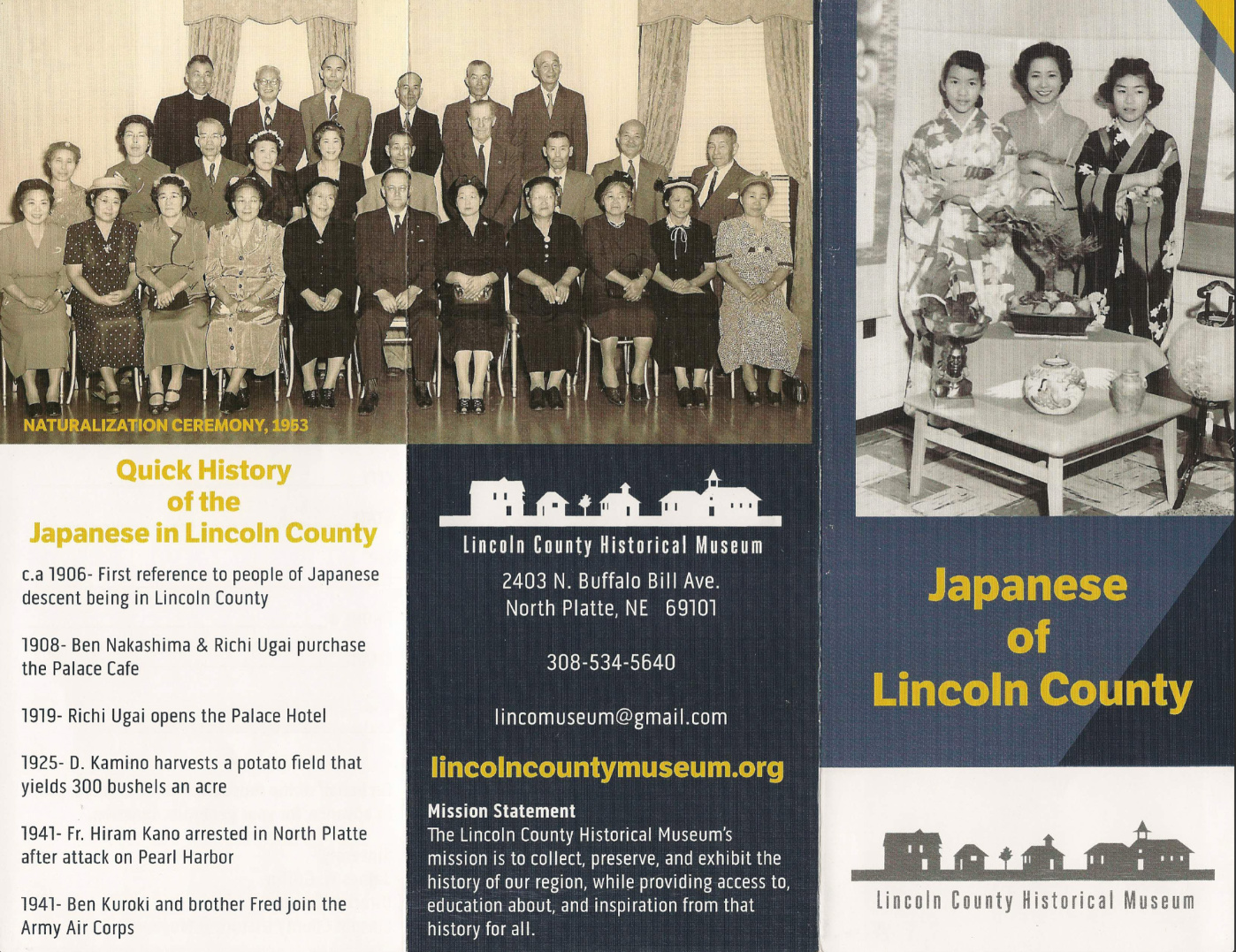

A new exhibit on Japanese Americans in Lincoln County, Neb., is set to open at the Lincoln County Historical Museum this fall. (Photo: Courtesy of Steve Kay)

Takeshi Okamoto to be featured in a new museum exhibit on the history of Japanese Americans in Lincoln County, Neb.

By Job Vigil, The North Platte Telegraph

The Issei joined the community in Lincoln County as the first generation of immigrants from Japan, working at the Union Pacific Railroad and farming throughout the county.

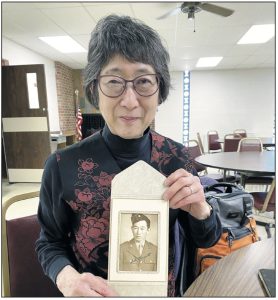

An exhibit at the Lincoln County Historical Museum is planned for an opening in the fall, and Barbie Okamoto Bach has contributed substantial photos and historic documents to the process. Bach grew up in North Platte, and her family has an extensive history in the area.

Barbie Okamoto Bach holds a photo of her father, Takeshi Okamoto, who lived and grew up in North Platte, graduating from North Platte High School in 1939. Okamoto served in the U.S. military as a language specialist during World War II before coming back to earn a Ph.D. in chemistry. (Photo: Job Vigil)

Her father, Takeshi Okamoto, was the firstborn of his family. Bach said they lived on West 10th Street, and her mother’s family, the Kumagais, lived on West Ninth Street.

Both families attended North Platte High School, and Takeshi led the way for his siblings and children.

“His dad worked off and on but had a lot of personal choice issues and health issues,” Bach said, “and my dad felt responsible for the whole family all the time.”

She said her dad was a hero who lived to the age of 92. He is buried at Fort McPherson National Cemetery, having served in the military as a language specialist during World War II.

After graduating from high school in 1939, Takeshi took several odd jobs, she said. He was most proud of his participation on the debate team in school.

“He also had some real academic achievements,” Bach said. “He was encouraged by his teachers to go far, which he thought was kind of surprising.”

Takeshi’s family all had Japanese first names, but that changed when they began attending high school.

“When they got to high school, they were all told that the teachers couldn’t deal with their Japanese names,” Bach said. “They had to adopt Anglo names, so they all did. My dad took the Anglo name Ted. His nickname was ‘Tuck.’”

She said after the start of WWII, Japanese were not accepted into colleges. During high school, Takeshi attended many Episcopal Church camps.

“Bishop (George Allen) Beecher adopted my dad,” Bach said. “My dad was kind of a tough boy, and Bishop Beecher wrote letters of recommendation to get my dad into Hastings College and paid for his tuition.”

Takeshi lived with the Beechers and served as gardener and chauffeur. He also was the sexton for the cathedral in Hastings.

“He lived with Bishop Beecher’s family and served the bishop and went to college at Hastings,” Bach said. “He was only there for a couple of years, then he was in the service.”

Takeshi was sent to Japan during Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s occupation. He served just a little over a year.

“After the service, he went to the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and got a Ph.D. in chemistry,” Bach said. “He didn’t have a lot of knowledge about how things work. I think it’s part of the immigrant experience because he never knew things he could have had.”

Bach said her dad was a real character.

“When I was little, he would tell me these stories,” Bach said. “He would say, ‘I was in the Nebraska penitentiary.’ I would say, ‘What?’”

He would answer, “Yes,” and would give her the date he was there, and Bach would response again with a “What?”

“What did you do?” Bach would ask him. “And he said, ‘Well, I drove a truck full of vegetables into the penitentiary.’ He was such a joker. He was always trying to make some crazy story.”

As a youngster, Bach said her dad always wanted to learn to fly airplanes.

“He saved up some money, and in his spare time, he was taking flying lessons,” Bach said. “It was just something he wanted to do. I don’t know if he wanted to make it a career thing, but I have his license.”

On the second page of the license, her dad wrote a notation: “I was scheduled to finish my certification to fly solo when I was called back because my dad’s stomach cancer, so I was called back home.”

She said he didn’t take his final test. The date on the certificate is 1941, which was right after high school and before he went to college.

“He saw himself as a farmer,” Bach said. “He was always telling me stories about sugar beets.”

Takeshi leased property and often had issues with water rights for irrigation.

“He told me these long stories, and some of it was different treatment for Japanese farmers than for others and the challenges of getting water rights and good land,” Bach said. “He was a real naturalist. He loved nature. He was always fishing.

“His career was as a research chemist,” Bach said. “His first job was with Monsanto in St. Louis, so we moved from Nebraska to St. Louis.”

In 1970, Takeshi took over the engine lab of Monsanto in England. The family moved there in 1972.

“He was in charge of that facility, and they called him ‘the governor,’” Bach said. “He worked in petrochemical research.”

The full story of the Okamoto and the Kumagai families will be part of the museum exhibit at the Lincoln County Historical Museum, as well as those of other Japanese families.

Jim Griffin, director/curator at the museum, said $100,000 has been raised to remodel the museum and build the exhibit. He said Bach has provided a plethora of historical pieces to anchor the project.

“From her, we have received a treasure trove of photographs,” Griffin said. “Their family photos and other photos from the Japanese community here in Lincoln County have helped us put together the story of the Japanese that settled here in Lincoln county. We’re super grateful for that.

“We’re still planning for the fall to open,” Griffin said. “We’re really excited to be able to remodel a whole section of the museum because of this project.”

He said the money was raised in just three months for the remodel project.

“It is allowing us to remodel that whole section,” Griffin said. “Half of it will be turned into the Japanese Americans of Lincoln County exhibit, and eventually when we raise more funds, the other half of that area will be made into an exhibit to tell the history of our airport.”

This article was reprinted with permission by Job Vigil and the North Platte Telegraph. For more information on the Lincoln County Historical Museum, visit lincolncountymuseum.org.