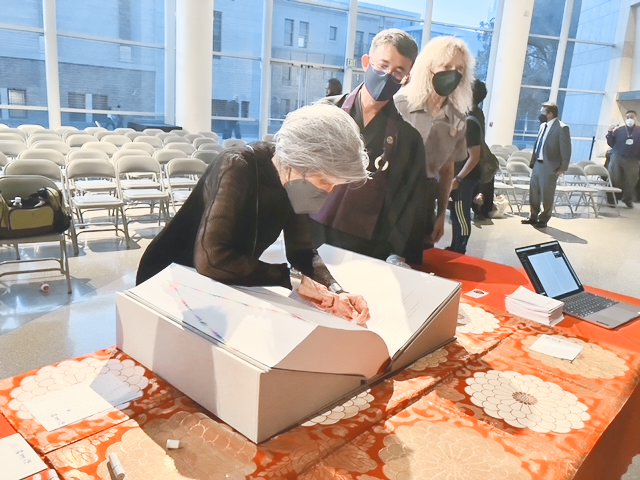

Barbara Takei makes her mark in the Ireichō honoring her mother and grandmother with Rev. Duncan Williams looking on. (Photo: Courtesy of Barbara Takei)

The newly installed Ireichō is an interactive memorial, but that’s besides the point. You are the point.

By Lynda Lin Grigsby, Contributor

Barbara Takei represented 27,000 souls in a procession to honor all Japanese Americans incarcerated during World War II.

Delegates from 75 WWII incarceration sites walk in the footsteps of history at the Sept. 24 installation ceremony. (Photo: Regina Boone)

The calendar officially said autumn, but on this September day in Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo, the oppressive heat begged to differ. Takei, a Sansei Florin JACL member, walked in the steps of history and carried the memories of those once imprisoned at Tule Lake, including her own family members. A steady taiko beat orchestrated her footsteps. Her mother, Sakaye Bette Takei, is a former Tule Lake incarceree who is listed in the Ireichō, or sacred book of names, a first of its kind comprehensive list of Japanese Americans affected by the WWII mass incarceration.

Bacon Sakatani (right), a San Gabriel Valley JACL member, holds the Pomona Assembly Center tablet and soil in the procession. He and his family were incarcerated there during WWII. (Photo: Kristen Murakoshi)

There is a precise soul count now of the harrowing Japanese American wartime experience: 125,284 persons. It’s a more accurate number than the oft-cited 120,000 thanks to Rev. Duncan Williams and a small group of historians and fact-checkers who scrutinized and cross-checked scattered records to create the list now published in an unassuming book with more than 1,000 pages sequenced in order of eldest to youngest.

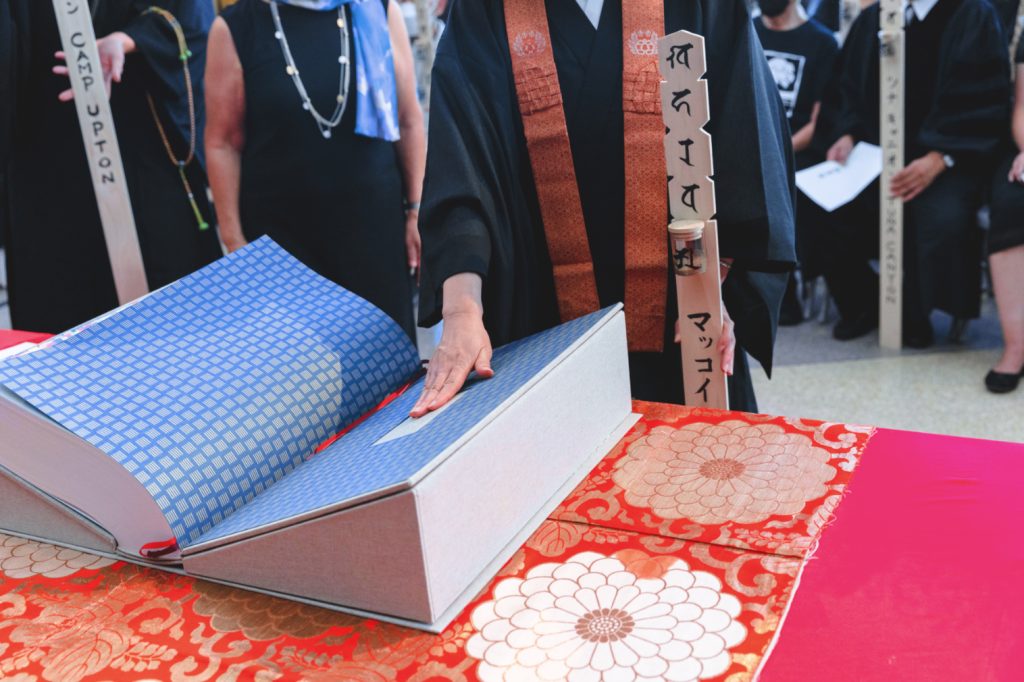

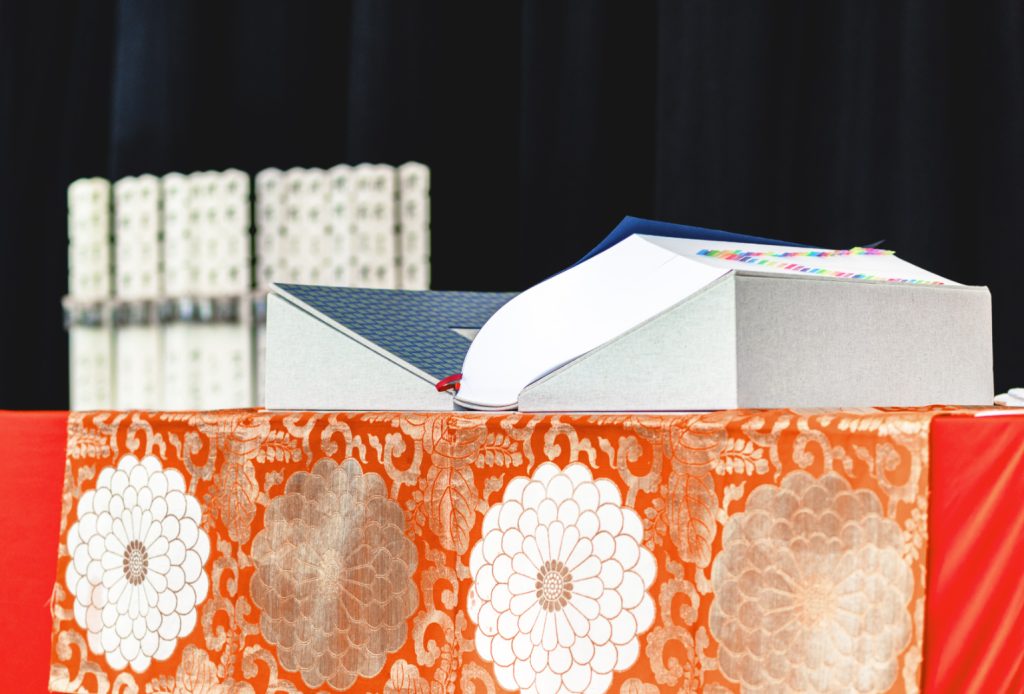

Hand-sewn together and now lying recumbent at the Japanese American National Museum waiting for affirmations and edits, the Ireichō is parchment color and hefty enough to need two people to carry because it, as Takei describes, is filled with souls.

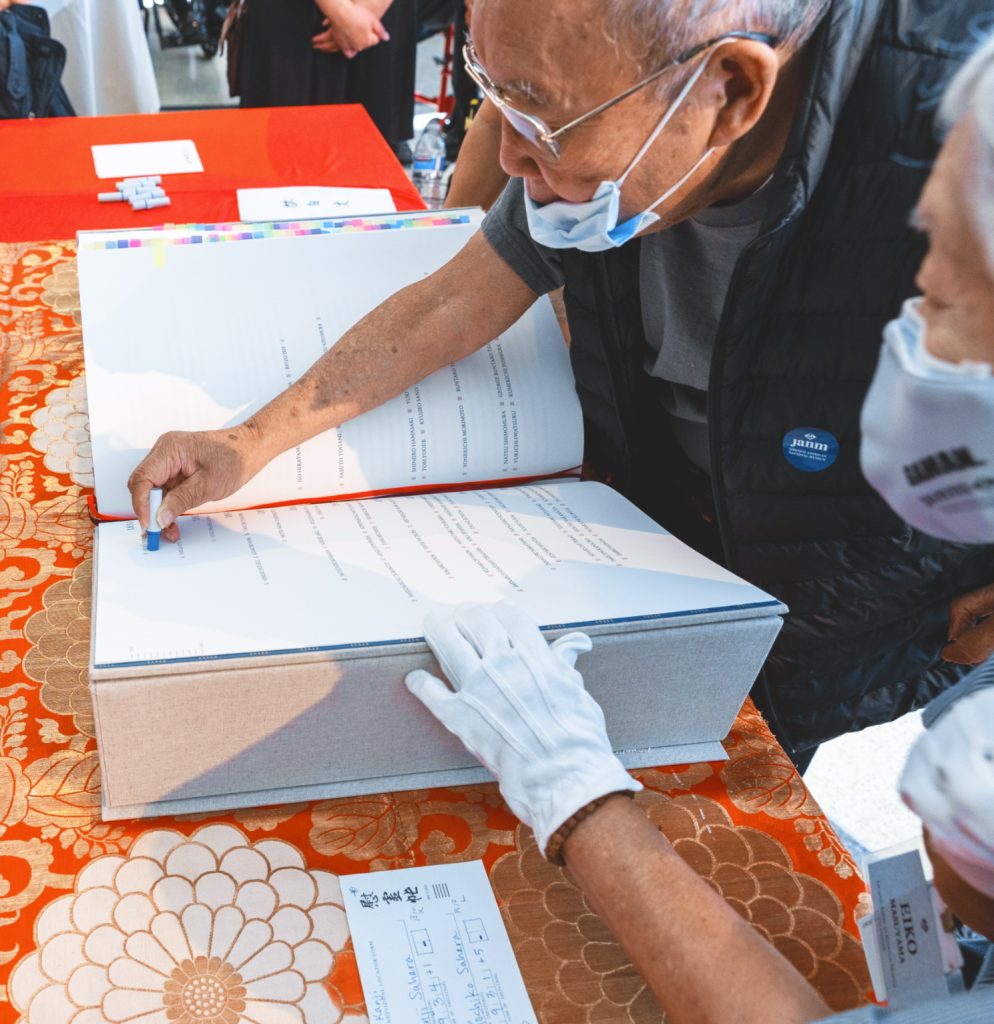

With the help of white-gloved official page-turners, Takei found her mother and grandmother’s names and carefully placed a small, circular blue stamp, or hanko, next to each. She felt like she was summoning their spirits.

“It made me a witness and a participant in the history captured by this iconic book of names, a manifest of the thousands of lives scarred by America’s injustice,” said Takei, 73.

The Tule Lake delegation (from left) Barbara Takei, Rev. LaVerne Sasaki and Hiroshi Shimizu

The multifaceted project is the latest memorial dedicated to the WWII Japanese American experience that seeks to remember what many history books omit. Traditional memorials seek to reclaim space and history through physical evidence of power — immovable granite and stone — but the thrust of Ireichō project differs in its impermanence.

The intent is not to take a pilgrimage to see the sacred book (though you should go see it during its yearlong residency at JANM). The aim is to get you to see yourself as the sacred artifact and a living part of history.

“We believe that a monument can be a living dynamic one that actually changes because of you,” said Williams to the delegates before the ceremony. “You become the monument.”

In a community that has already wrested an apology and compensation from the U.S. government for its actions during WWII, the Ireichō project also underscores the need for continual repair because not all wounds heal after one apology.

The Particles Are Settling

The Sept. 24 installation ceremony at JANM had all the pomp of a major sporting event’s opening ceremony, a deliberate choice that Williams, 53, acknowledged a week before the event when we met at the museum in a room in the shadows of his current exhibit, “The Sutra and Bible.”

Naomi Dyo Wagner, a Tulare descendant, carries family pictures and memories. Japanese Americans were imprisoned on grounds formerly used by the Tulare-Kings County Fair. (Photos: Kristen Murakoshi)

“To kick it off right, we wanted to have a strong installation ceremony,” said Williams, bespectacled and wearing shoes with loose laces that danced as he rushed through the museum. He is director of the USC Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religion and Culture and a Buddhist priest who often closes his eyes when he talks about the Buddhist traditions interwoven into the memorial (the number five is a motif).

On the day of the Ireichō ceremony, delegates representing 75 WWII confinement sites walked in a procession through JANM’s campus — from the former site of the Nishi Hongwanji Buddhist Temple to the glass-encased Aratani Central Hall — carrying wooden tablets with names of the camps, military bases or detention centers that once imprisoned people based on their ethnicity. The sites included more well-known ones like Manzanar and obscure ones like Fort Howard, a place just beyond Baltimore, Md., where in 1941 the FBI imprisoned Tsuruju Miyazaki.

Prewar, Miyazaki owned the Horseshoe Café in Suffolk, Va., and Mike’s Café in Norfolk, Va.

In the segregated Southern state, Miyazaki met Lethia Mae Boone and had two children. His entrepreneurial success likely led to his arrest hours after the Pearl Harbor attack — FBI agents targeted prominent Issei men and community leaders as potential threats to national security. No Issei men were convicted of such crimes, but their imprisonment changed their lives forever.

Miyazaki died of tuberculosis before he could reunite with his family in Virginia. He left behind two young children, including a toddler son, Raymond H. Boone, who grew up with questions swirling about his mysterious father. Before he died in 2014, Boone asked his daughter to tell Miyazaki’s story.

“That was a heavy lift,” said Regina Boone, 52, Miyazaki’s granddaughter. “Our whole family was disrupted due to racism.”

Regina Boone’s grandfather, Tsuruju Miyazaki, was imprisoned at Fort Howard, a place just beyond Baltimore, Md. (Photo: Kristin Murakoshi)

Regina Boone is a staff photojournalist with the Richmond Free Press, a weekly newspaper that her parents founded in 1992 in the former capital of the Confederacy. Her research led to Minamishimabara, a city in the Nagasaki prefecture of Japan, her grandfather’s hometown, where she met family members who affectionately referred to Miyazaki as “Uncle America” and displayed his ashes on the family’s Buddhist altar. She paid respects to the grandfather she had never met. Over the phone from Richmond, Va., Regina Boone compares herself to a snow globe.

“It’s kind of like when you’re asking me these questions, all this stuff is shaking up in my body,” she said. “But then because I know the answers now, I’m not as stressed out because I do know my story so well. The particles are settling, so I can breathe a little better.”

Days later in the Ireichō procession, Regina Boone carried the Fort Howard marker. Dressed in all black save for the pop of turquoise bracelets around her wrists, she walked with a sporadic flow of tears. Your ancestors are so proud of you, other delegates whispered. Then, she imprinted a blue stamp next to Miyazaki’s name.

“I thought to myself, ‘My grandfather must be listening and standing tall knowing we are collectively righting a wrong in the most amazing way,’” said Regina Boone.

The dominant narrative of the WWII Japanese American experience often cites 120,000 (a now imprecise number) lives uprooted from the West Coast. This narrative, which casts Regina Boone’s family history to the periphery in part because Miyazaki lived in the South, is decidedly being rewritten through a more inclusive lens with the Ireichō.

“What we tried to do was make sure that nobody’s left out,” said Williams to the delegates before the procession. This includes people who died while incarcerated or were forced to work in sugar beet fields. It’s an acknowledgement that every life disrupted during WWII counts. The Boone family never received an apology or monetary compensation from the U.S. government for the wrongful incarceration. The 1988 redress bill only included living survivors, but at what cost can you affix to a life and intergenerational trauma?”

“There’s no monetary amount that’s ever going to wipe away the pain and agony and everything that happened to all of these families — all people of Japanese descent, all people who intersected into this community,” said Regina Boone.

Repair is transitory. It can change and morph. What heals for one person can rupture again a generation later, so the danger of memorializing historical events is that it pretends to be only about the past when the act of affixing a civic memory also includes the present.

This project is very much a look at the Japanese American WWII experience through a 2022 lens — post George Floyd’s murder and the toppling of Confederate monuments. It’s a step away from the traditional definition of a permanent memorial, but what happens when sentiments change and the need for repair morphs?

The answer lies in the book’s timeless focus on accuracy. It personalizes and humanizes the impact of the WWII Japanese American experience and brings into focus names and identities behind the number 125,284.

The Ireichō, a sacred book of names to console ancestors, is filled with souls. Rev. Duncan Williams consecrates the book. (Photo: Kristen Murakoshi)

“After the campaign to repair the historical record comes to a conclusion, the deeper work of repair continues as we encourage ever-widening circles of the American public to continuously reckon with the racial karma of our nation’s past,” said Williams.

Ceramic art pieces are embedded on the inside front and back covers of the book. The pieces were created using soil from the 75 sites. (Photo: Kristen Murakoshi)

The beauty of the Ireichō is in its thoughtful curation of Japanese traditions using five elements: wood (the paper in the book), earth (representatives were asked to bring soil samples from each confinement site), fire (represented by ceramic pieces embedded in the inside front and back covers), metal (the gold font on the cover) and water (the blue stamp).

The idea borrows from the Buddhist tradition of writing and reciting ancestors’ names as an act of bringing the past and the present together. For a community to be made whole, every individual must be counted.

This project, Williams said, is also about correcting the historical record. During the war, Japanese American names were often misspelled or replaced completely with unique numbers.

“We know what the power of names is,” said Ann Burroughs, JANM’s president and CEO, during her address of the ceremony’s delegates.

The Ireichō seeks to restore power to those names and identities. Its residency at JANM is a yearlong effort to correct the official record. Survivors and descendants can book a timed reservation to view the Ireichō and correct misspellings or omissions.

Survivors and descendants are invited to stamp the book and make corrections. (Photos: Kristen Murakoshi)

The goal is to get the official record right. The Ireichō is the first part of a multifaceted project that includes a website (ireizo.com) and an Irehi, or soul consoling tower monument, like the one at Manzanar.

A memorial like this is not a magic balm that heals all wounds, but it can offer an opportunity to perform a ritual for self-reflection and self-care.

“Rituals deepen our understanding of something that happened in the past, and also rituals can give us much hope for the future,” said Rev. Jiko Nakade, a Sansei Buddhist minister of the Soto Zen sect at the Daifukuji Soto Mission in Hawaii.

In 1942, Nakade’s grandfather, Kanesaburo Oshima, an Issei man imprisoned at Fort Sill, Okla., felt despondent over his protracted separation from his wife and 11 children. Despondency grew to desperation as he wandered to the fence line at Fort Sill, mumbling, “I need to go home.” The guards shot Oshima in the back of the head.

In the Little Tokyo procession, Nakade, 60, clutched the black-and-white portrait of the grandfather she never knew to her black-and-mustard-colored robe. Through ritual and ceremony, she is feeling more connected to her past.

“Suddenly, [my grandparents’] pictures and their faces, which are kind of etched in my memory from childhood, have deep meaning for me now,” said Nakade.

The Ireichō itself is a macguffin, an object that is necessary to the plot of the retelling of this historic event, but is also irrelevant. Go see the book and feel the gust of wind when the pages are turned. The impact of racism is sobering. Then, go talk to survivors and descendants such as Takei or Regina Boone.

They are the true monuments.

How to Honor Your Ancestors in the Ireichō

Starting Oct. 11, the Ireichō will be available for stamping from 12-4 p.m. on Tuesdays-Fridays and 11 a.m.-4 p.m. on Saturdays and Sundays. Museum admission is not required, but reservations are required. Each person stamping will have 15 minutes to go through the process, including creating a memento with the names, completing the research, stamping (limited to two names) and making any corrections if necessary. The Ireichō will be available at JANM for one year.

Reservations can be made at janm.org/exhibits/sutra-and-bible/ireicho.

Guests are encouraged to visit ireizo.com to prepare, locate, verify and amend records of the former WWII incarcerees.

(Photo: Kristen Murakoshi)