Akira and Hideko Nagamine today, surrounded by their beloved cucumber plants (Photos: Courtesy of the Nagamine Family Collection)

The Watsonville, Calif.-based family farm works to ‘honor the Issei, our heritage and to cultivate community.’

By Emily Murase, Contributor

Organic Japanese cucumbers from Watsonville, Calif.-based Hikari Farms have arrived in San Francisco Japantown in a big way. Available at local Japanese supermarkets for years, these deliciously crunchy cucumbers are now available directly from the farm, together with other Japanese vegetables, at monthly pop-ups at the Konko Church of San Francisco and Japantown community events, most recently the Japanese Cultural and Community Center of Northern California’s signature “Tabemasho” fundraiser.

Hikari Farms signage at San Francisco’s Bi-Rite Market, featuring its all-organic produce (Photo: Courtesy of the Nagamine Family Collection)

The tale of these beloved cucumbers traces the origins of Japanese immigrant farming since the early 1900s, the many challenges family farms face today and Nikkei resilience across generations.

Hideko Nagamine preps sweet Japanese cabbage. (Photo: Courtesy of the Nagamine Family Collection)

According to a detailed history of Japanese farm labor in the Watsonville area by Jane Borg and Kathy Nichols, an early immigrant farmer was Unosuke Shikuma, who started out in 1902, working onion fields for $1.

In 1903, he began growing berries with other Issei farmers. Soon, he became an independent strawberry farmer with enough resources to recruit sharecropper families and provide them with housing.

By 1920, Shikuma joined four other growers who, together, became the largest strawberry ranch in the world by revolutionizing the industry. While, previously, strawberries were transported in large chests by rail, the partnership radically changed shipping technology by filling wooden trays, each with a dozen small baskets, distributed in refrigerated trucks.

In response to a worker shortage, a new government program to bring up to 1,000 Japanese guest workers to California farms on three-year contracts arose from a collaboration of the California Farm Labor Assn., the California Farm Producers Assn., the Japanese Consul of the West Coast and the Ambassadors of the U.S. and Japan.

According to Mireya Loza of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, who authored a well-documented history of the Japanese Agricultural Workers’ Program (1956-65), the program was not without its critics.

Members of the JACL Central California District Council expressed concerns given “the bitter history of agricultural labor exploitation … and hard-won postwar community acceptance of those of Japanese ancestry.”

Loza explains that after hearing from JACL National President Roy Nishikawa and Washington, D.C., Representative Mike Masaoka about the program’s importance to aiding the devastating economic situation and destabilized political environment in Japan, the JACL’s CCDC eventually gave its support to the Japanese guest-worker program.

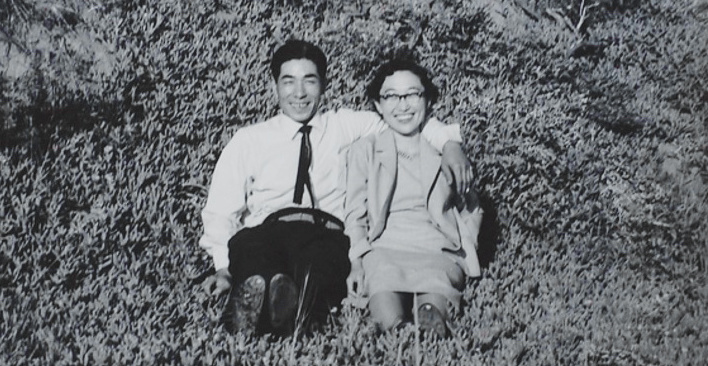

Newlyweds Akira and Hideko Nagamine (Photo: Courtesy of the Nagamine Family Collection)

In 1956, Shikuma traveled to Japan to recruit workers for his farm. Among the eight young men he selected was Akira Nagamine, who decided to leave his ancestral home in Kagoshima and board a ship bound for San Francisco to join the Shikuma Ranch in Watsonville with just $24.32 in his pocket. Joining Akira was his wife, Hideko Fukutome, a Kibei from Denver who had moved to Kagoshima as a child. Hideko worked the strawberry fields as well, earning $.40 per crate.

Akira Nagamine shows off his fully furnished apartment in a photo sent back to his family in Japan. (Photo: Courtesy of the Nagamine Family Collection)

By 1962, Akira Nagamine was able to pool capital with his brother, Osamu Nagamine, and brother-in-law, Hachiro “Harry” Fukutome, to purchase five acres of a former apple orchard on Condit Lane in Watsonville.

According to a 1973 interview with Harry Fukutome conducted by Borg and Nichols, the Nagamine brothers decided to become one of just three carnation flower growers in the area, building on experience Akira and Hideko gained from working in flower hothouses in Mountain View, Calif., after their contract with the Shikuma Ranch expired.

Just five years later, Akira purchased additional acreage and established A. Nagamine Nursery in 1967; he then moved his wholesale florist operations to a new location on Freedom Boulevard in Watsonville.

At the new, larger location, the family built a thriving business focused on carnations, chrysanthemums and roses.

Akira’s two sons joined him during the 1980s. However, in the mid-1990s, new international trade agreements, in particular the North American Free Trade Agreement, paved the way for an influx of low-priced South American flowers, thus threatening the family business.

Fifty-two tons of scrap metal are removed from the farm as the family prepared to reorganize its operations. (Photo: Courtesy of the Nagamine Family Collection)

In response, the farm became one of the first family farms in the area to transition to organic vegetables in 1998, as Akira Nagamine switched to growing organic cucumbers, tomatoes and beans for retail outlets and farmers markets.

Akira Nagamine with his custom-built watering tool that releases just enough water for each cucumber plant (Photo: Courtesy of the Nagamine Family Collection)

By 2014, however, the future of the farm became uncertain, as Akira and Hideko were well into their 80s and their sons, after years of dedicating themselves to the family farm, sought to pursue other professional interests. The family decided to terminate the family business.

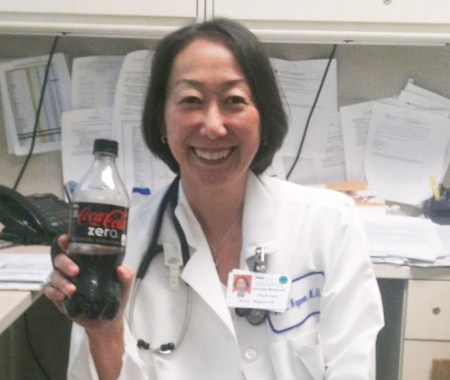

It was up to daughter Janet, by then a medical doctor, to prepare the farm for lease. She took a leave of absence from her medical practice in the Silicon Valley, expecting to return in a few months.

Dr. Janet Nagamine at work at Kaiser Hospital; today, she works a doctor-farmer career track. (Photo: Courtesy of the Nagamine Family Collection)

Janet embarked on the physically and emotionally demanding job of clearing out a lifetime of sentimentally important yet obviously obsolete or irreparably damaged farm equipment under the watchful and sorrowful eyes of her father. She arranged for 52 tons of scrap metal to be removed.

While Janet dealt with scrap metal and potential lessees, her father, Akira, asked if he could tend to “just a few cucumbers.” Despite the busyness of her days, Janet could not help but observe her father devote himself absolutely to his craft: how he talked to the plants, understood exactly the amount of water they needed, delivered to them that water via a handcrafted tool he designed and built and cared for each cucumber growing joyfully on vertical trellises.

It became clear to Janet that she could not let go of the family farm. She did a cost-benefit analysis and concluded that the reasons to continue farming greatly outweighed the cons: “to keep the legacy, culture and traditions alive; keep connections to Kagoshima and Japan.”

Rather than return to her medical practice full-time, Janet decided to choose a nontraditional doctor-farmer career track, saying, “Farming is kinda cool and beautiful, and it’s preventative medicine, too!”

Grandpa Nagamine with his granddaughter on his forklift at the farm (Photo: Courtesy of the Nagamine Family Collection)

Janet rebranded A. Nagamine Nursery to Hikari Farms. She consulted her parents and landed on hikari, which means “shining light” in Japanese.

“The name allowed us to move forward in a positive light,” she said, adding that “plants are derived from life and light.”

Moving forward with Hikari Farms, Janet focused on traditional Japanese vegetables and worked on finding new markets, especially for her father’s cucumbers. She concluded a contract with Bi-Rite Market in San Francisco.

Unbeknownst to her, Bi-Rite started to brand Hikari Farms cucumbers as an ingredient in its sushi rolls. Then, members of the Japanese American community in Palo Alto, Calif., and San Francisco stepped up to connect Janet directly to customers for Japanese specialty vegetables such as komatsuna mustard spinach and rakkyo scallions through a monthly farm box program started in Palo Alto, as well as a monthly pop-up in San Francisco at the San Francisco Konko Church.

Today, Janet’s parents continue to tend to the farm at ages 101 and 97. Her father, Akira, expresses his gratitude for each day that he is able to care for his now-famous cucumbers, and her mother shares her recipes for many dishes freely.

In addition to growing their organic produce, the farm also hosts private events for customers and holds its annual family New Year’s mochitsuki. Janet also continues to strengthen the farm’s relationship with Japan through various trainee and seed programs, in addition to preserving the regional foods of her father’s roots in Kagoshima.

“The reception of the farm and what it means to others has been heartwarming and inspiring,” said Janet. Her goal is not only to provide Japanese produce to restaurants and communities but also “to work to honor the Issei, our heritage and to cultivate community.”

Emily Murase’s favorite Hikari Farms product is the rakkyo scallions, which she had an opportunity to peel on a recent visit to the farm.

Prepping Nagamine rakkyo scallions (Photo: Courtesy of the Nagamine Family Collection)