Topaz survivors and friends gather during the 80th anniversary commemoration of the murder of James Wakasa in San Francisco. (Photo: Emily Murase)

A memorial event is held in San Francisco to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the slaying of James Wakasa.

By Emily Murase, Contributor

The Wakasa commemoration took place in San Francisco Japantown’s Peace Plaza. (Photo: Emily Murase)

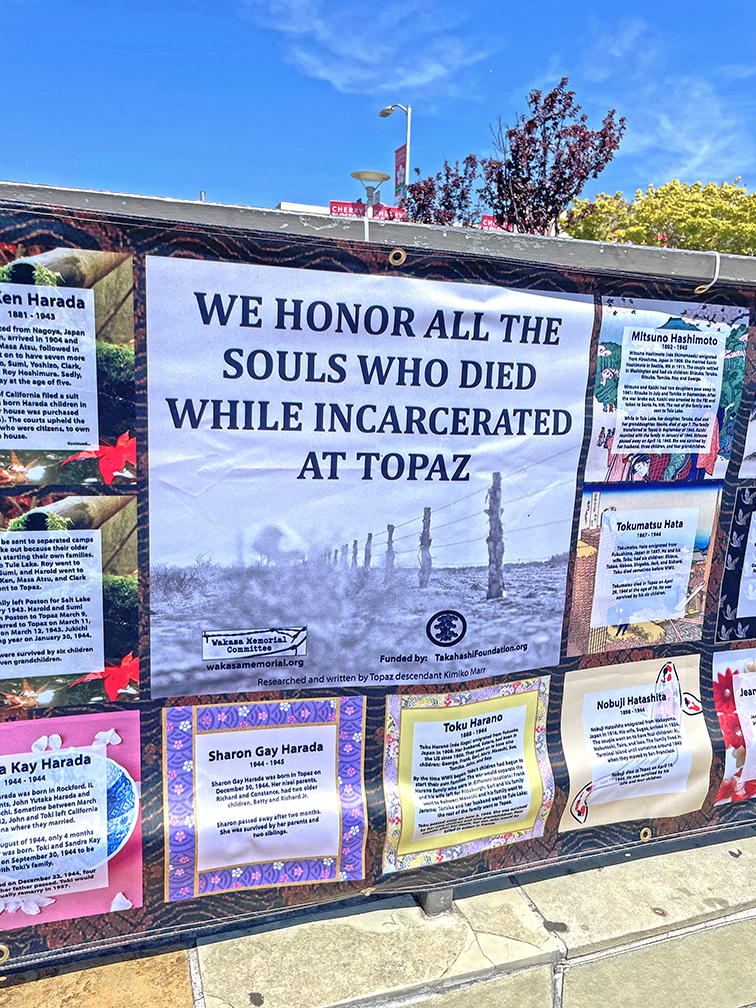

Under bright skies in San Francisco Japantown, delicate cherry blossom petals swirled around the 80th remembrance of the murder of James Hatsuaki Wakasa at Peace Plaza on April 11. Organized by the Wakasa Memorial Committee in partnership with the San Francisco Recreation and Parks Department, which oversees the venue, the event drew dozens of survivors and descendants of Topaz and other U.S. concentration camps, as well as their families and friends who wished to pay tribute to wartime survivors and veterans.

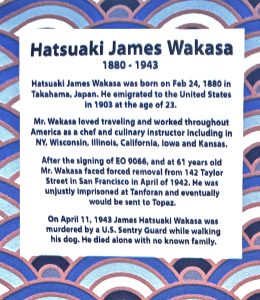

A close-up of James Wakasa’s quilt square (Photo: Emily Murase)

Due to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s signing of Executive Order 9066, which required the removal of individuals of Japanese descent from the West Coast, 8,000 San Francisco residents were forcibly removed to Topaz, Utah, a remote, barren location during World War II. According to Lisa Barr of the Utah Division of State History, an additional 3,000 people from Washington, Oregon and Hawaii were also assigned to the primitive prison camp.

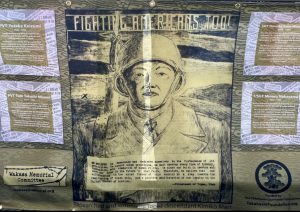

There, in the harsh Utah desert, the incarcerees suffered immeasurable hardships, and many did not survive. As a backdrop for the commemoration event, the Wakasa Memorial Committee created banners of quilt squares to display, with each square commemorating an incarceree or veteran whose life was lost during wartime.

Wakasa, an Issei, immigrated to the U.S. in 1903 to pursue a culinary career after attending Keio University in Japan. On April 11, 1943, Wakasa, 63, was walking his dog after dinner when he was killed by a bullet to the chest that was fired by Pvt. 1st Class Gerald Philpott, 19, a military police sentry who was in a guard tower, according to Topaz descendent and researcher Nancy Ukai. Philpott was court-martialed but acquitted of all charges, unbeknownst to the Topaz incarcerees.

A funeral ceremony photo of James Wakasa’s memorial service at Topaz on April 19, 1943

Grief-stricken incarcerees asked that a memorial service be held at the location where Wakasa was killed. Fearing organized unrest and possible riots, prison authorities denied the request and ordered the memorial to be held at a different location. According to local news reports, more than 2,000 incarcerees attended the April 19, 1943, service.

Pictured (from left) are musician Lewis Jordan, Topaz-born Masako Takahashi and archaeologist Mary Farrell (Photo: Emily Murase)

A purification blessing was conducted by Rev. Masato and Alice Kawahatsu. (Photo: Emily Murase)

The remembrance event opened with an indigenous land acknowledgement by Topaz-born Wakasa Memorial Committee member Masako Takahashi, followed by an interfaith tribute to Wakasa, incarcerees and veterans of Topaz and other incarceration sites.

Rev. Masato Kawahatsu and his wife, Alice, performed a purification blessing in the Konko tradition, and Topaz descendant Rev. Michael Yoshii, the celebrated pastor of Buena Vista United Methodist Church (retired), spoke about the collective trauma suffered by the Topaz incarcerees who also demonstrated tremendous resilience.

Topaz descendant Rev. Michael Yoshii (Photo: Emily Murase)

Rev. Yoshii explained that Wakasa’s funeral was the joint effort of six members of the clergy representing a diverse group of faiths, and featured the hymn “Rock of Ages,” which was sung in Japanese by Kaoru Inoue. The hymn refers to seeking refuge in God as a rock during hardship and remains particularly timely to this day, the week of Easter and the resurrection of Christ.

Following the interfaith blessing was musician/poet/educator Lewis Jordan’s live performance of “Rock of Ages,” the very same hymn that was featured at Wakasa’s funeral 80 years ago.

The Wakasa Memorial Committee quilt honoring Poston individuals who passed away while incarcerated. (Photo: Emily Murase)

A few short days after Wakasa’s funeral, outraged and grief-stricken incarcerees erected in tribute to Wakasa a nearly six-foot-tall stone monument, estimated to weigh half a ton, on the very spot of his murder. When it was discovered by prison authorities, the monument was ordered to be taken down immediately.

The Wakasa Committee tribute to veterans (Photo: Emily Murase)

However, in a secret that was only unearthed in 2020 when, according to John Ota, writing for “EastWind,” archaeologists Jeff Burton and Mary Farrell, following a hand-drawn map that Ukai found in the National Archives, discovered that the memorial stone had not been destroyed and was instead buried on the Topaz grounds, undisturbed for 77 years.

Farrell was a featured speaker at the San Francisco memorial event. When Farrell and her partner, Burton, discovered the long-buried stone monument, Takahashi, who leads the Henri and Tomoye Takahashi Foundation, offered to assist in the professional excavation and preservation of the stone. However, the privately owned Topaz Museum declined the offer and instead, without input from the Japanese American community, unearthed the monument using untrained methods, thereby damaging the stone.

The Wakasa Memorial Committee advocates for placing the Wakasa Memorial Stone and the Topaz Concentration Camp under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service, rather than private ownership, as is the case currently.

In her remarks, Farrell explained, “The stone has a lot to say. It shows that the Topaz prisoners did not accept the narrative that Wakasa’s shooting was a ‘justified military action’ as alleged by prison authorities. … The Issei went to a lot of trouble to build, then bury the monument.”

Topaz survivor Kiyoshi “Kenny” Ina (Photo: Emily Murase)

Farrell urged the community to advocate to the NPS to sponsor a community archaeology project at Topaz, similar to previous efforts conducted at the Manzanar National Historic Site, where survivors, descendants, family members and friends can work together to uncover remnants of the life the incarcerees experienced there. She also explained that such projects facilitate community healing for the generations of harm caused by the wartime incarceration.

Poston survivor Chizu Omori places a paper flower offering during the ceremony. (Photo: Emily Murase)

Another featured speaker was Topaz-born Dr. Patrick Hayashi, who retired as associate president of the University of California system. In describing the monument, Hayashi stated: “The first time I saw the monument … I thought it was beautiful. On the outside — it is plain and simple, solid and strong, just like our parents and grandparents. But on the inside, it is rich, complex and deep.

“My mother’s spirit lives there. The monument embodies not just my mother’s spirit, but the spirit of all the people who were imprisoned in Topaz,” Hayashi continued.

In his remarks, Hayashi also criticized the handling of the memorial stone and mourned the controversy that has ensued since its excavation, but concluded, “Today, we pledge to fight together to make sure that what happened to Mr. Wakasa will never happen again — not to us, not to our community, not to anyone.”

Topaz descendant and Wakasa Memorial Committee member Nancy Ukai (Photo: Emily Murase)

Ukai, the final speaker, spoke about her journey as a founding member of the Wakasa Memorial Committee. She has dedicated her efforts to gather information about James Wakasa. Recently, she traveled to Wakasa’s hometown of Takahama in Ishikawa Prefecture, where she was welcomed warmly by local families.

A paper heart for James Wakasa (Photo: Emily Murase)

Paper flowers were dedicated during the memorial. (Photo: Nancy Ukai)

Ukai discovered many new supporters of the effort to remember Wakasa. In fact, upon her return to the U.S., she brought with her folded origami cranes and paper flowers that were made by those supporters to share at the memorial services.

The memorial concluded with survivors and descendants of Topaz and other U.S. concentration camps making offerings of paper flowers to the Wakasa altar.

In many ways, the remembrance event demonstrated the resilience of the many incarcerated individuals and families, including James Wakasa, not unlike the cherry blossom trees on the San Francisco Japantown Peace Plaza that have survived a year of strong elements but have continued to bring joy to generations of residents and visitors alike.

The hourlong San Francisco Wakasa remembrance ceremony can be viewed on YouTube at youtube.com/watch?v=-0iHGQiklL0.

Emily Murase, whose father was incarcerated in Poston, writes from San Francisco Japantown and serves as executive director of the Japantown Task Force. Funding for this article was provided by the Harry K. Honda Memorial Journalism Fund, which was established by JACL redress strategist Grant Ujifusa.