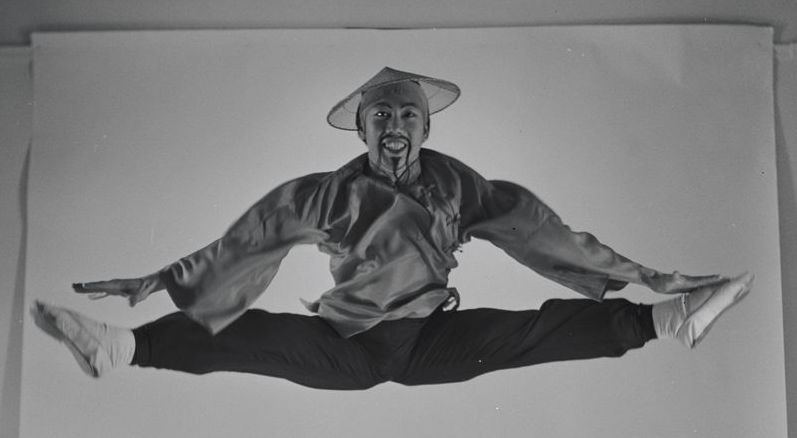

George Lee, circa the early 1950s, shows off his athleticism and flexibility for a divertissement called “Tea”

that was part of a production of “The Nutcracker.” (Photo: Courtesy of the filmmakers)

Decades after leaving the world of dance, a documentary offers George Lee a new deal.

By Gil Asakawa, P.C. Contributor

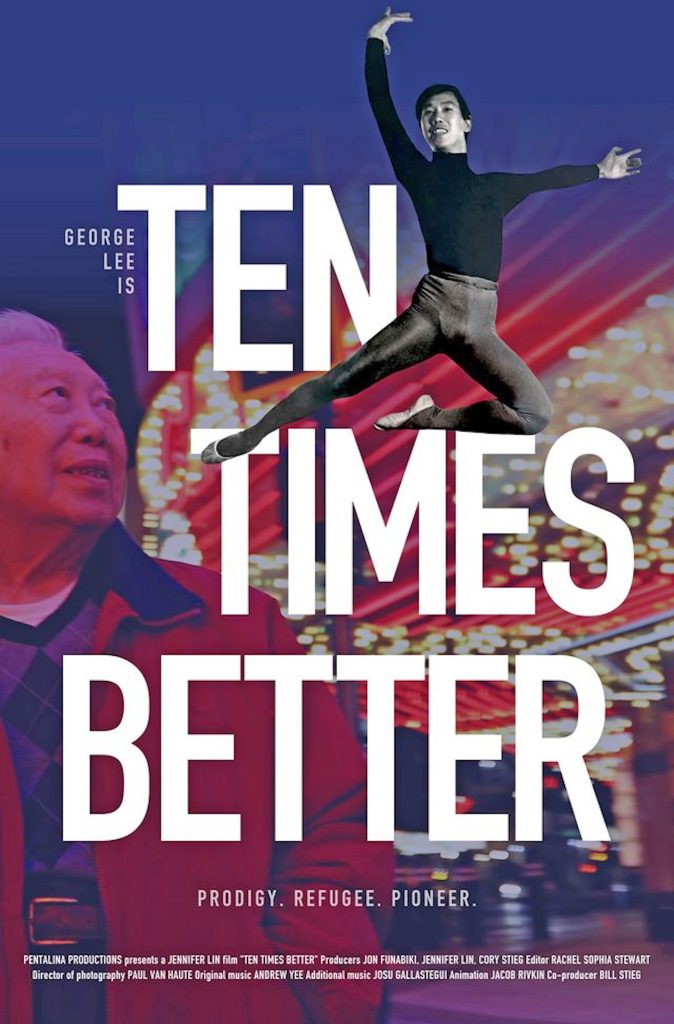

Few people would know the name George Lee. But once upon a time, he was an Asian pioneer of dance, in ballet and on Broadway. He may be forgotten today, but filmmaker Jennifer Lin and producer Jon Funabiki want to remedy that lapse and remind the world of Lee’s importance in a new documentary, “Ten Times Better.”

Few people would know the name George Lee. But once upon a time, he was an Asian pioneer of dance, in ballet and on Broadway. He may be forgotten today, but filmmaker Jennifer Lin and producer Jon Funabiki want to remedy that lapse and remind the world of Lee’s importance in a new documentary, “Ten Times Better.”

Lin didn’t know about Lee either, but she came across a photo and rave reviews of a young Asian dancer chosen by the legendary choreographer George Balanchine in the New York City Ballet’s 1954 premiere of Tchaikovsky’s “The Nutcracker.” He cast Lee for the suite’s “Tea Divertissement,” which is commonly called “The Chinese Dance.” The number was usually performed by white dancers in yellowface.

Lin was researching the early days of “The Nutcracker” for a documentary, “Beyond Yellowface,” about the history of casting white dancers in Asian roles in the arts. Lin and Funabiki (both are former reporters, and Funabiki still teaches journalism) were working on the yellowface documentary together.

“And specifically, ‘The Chinese Dance’ in ‘The Nutcracker’ is an element of that story,” Lin said, so she asked the New York City Ballet for any material from the 1954 performance. While looking through a box of publicity photos, Lin was surprised to come across a photo of Lee.

“And I thought, ‘Wow, I didn’t realize that the New York City Ballet back in 1954 had an Asian dancer,’” Lin said. “So, I was poking around the files. And I also saw newspaper clips and reviews of the premiere because it was an instant hit, as you can imagine. And many of the reviewers actually cited George Lee and said how phenomenal he was how not only was he incredibly acrobatic and athletic, he was a good dancer.”

But after that debut, Lee’s trail went cold. “The thing that really was the catalyst to trying to find George Lee is the fact that after ‘The Nutcracker,’ he never performed again for the New York City Ballet,” said Lin. “So, I could find no trace of him really with other ballet companies at the time. I became obsessed with trying to find George Lee and asking him what happened. Because if he was good enough for George Balanchine, he certainly was at the top of his game.”

When he found that he couldn’t get a lot of positions dancing ballet, Lee was told by the Hollywood star Gene Kelly that he should pursue roles in Broadway musicals. And that’s what he did, most notably in the stage and touring productions of “Flower Drum Song,” the pioneering musical starring Asian Americans that was set in 1950s Chinatown.

After Lin found a clipping that Lee had become an American citizen, that gave Lin enough information to research him on Ancestry.com. Using dogged reporter skills, she found five George Lee phone numbers, and the last one she left a message for called back.

“And he said, ‘This is George Lee.’ I said, ‘George Lee, the ballet dancer?’ He goes, ‘Yes, this is George Lee, the ballet dancer, but why are you looking for me?’ And then he added, ‘You know, I was nobody. So, why are you looking for me?’ And that was our first phone call,” recalled Lin.

As a youngster, George Lee performed a classic Russian Trepak dance in Shanghai nightclubs.

(Photo: George Lee Personal Collection)

She learned that Lee, now 89 but still mentally sharp and full of amazing stories, was a biracial son of a Polish ballerina and a Chinese acrobat in Shanghai who died when he was young. His mother raised him to be a ballet dancer with strict Russian-style instruction, and he still credits her for his success. She’s the one who took him as a refugee to safety, first in the Philippines and eventually to the United States, and gave him the advice that stayed with him through his dance career: He had to be 10 times better than the Americans to be taken seriously.

“I will always remember Jennifer’s excitement when she called me or sent me emails to give me the latest update about what she learned,” Funabiki said. “She would say: ‘Can you believe this story? … He used to perform in the Shanghai nightclubs when he was just a child! . . . They spent two years in a refugee camp in the Philippines . . . in the jungles! . . . George Balanchine picked him for ‘The Nutcracker!’ These were the tidbits that Jennifer would share with me as she learned more and more from George.”

“Beyond Yellowface” was put on hold for “Ten Times Better,” which has a running time of 31 minutes, so the team could tell Lee’s story quickly. It serves as a keystone for “Yellowface” because Lee was the dancer who was able to succeed on his talent in spite of resistance to Asians in ballet — at least for a while.

“Clearly, he wanted to do more in ballet, but people said he was too short or that he wasn’t the right ‘type’ for the parts that he auditioned for,” Funabiki added.

Lin and Funabiki arranged to meet Lee at his post-dancer workplace, as a blackjack dealer at the Four Queens Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas for the past 40 years. He chose his new career when he was performing in Vegas. He knew he couldn’t dance forever, so he got out of showbiz.

George Lee at the Four Queens Casino in Las Vegas, where he works as a blackjack dealer (Photo: Petalina Prods.)

“What struck me the most was how gentle and humble George seemed to be,” recalled Funabiki about meeting him in person. “He brought a lot of his old photographs and memorabilia to show to us. Clearly, he was proud of his accomplishments, but not in a bragging sort of way.”

Lee’s co-workers at the casino didn’t know about his life as a dancer. But when he went to a reunion of the cast of “Flower Drum Song” — both the Broadway production and the Hollywood film version — from the late 1950s and early ’60s, he was warmly received as a long-lost colleague.

The documentary has also revived the glories of his past career with the New York dance world.

When Lee attended a New York screening of the film, Lin says, “As we walked out on stage, everyone spontaneously started applauding. There were more than 200 people in the auditorium, including the president of the New York City Ballet, the artistic director of the New York City Ballet and the executive director of the School of American Ballet, which is the premier ballet academy in the United States. All of these people were there to hear George’s story. And everyone was applauding.

“And so, the man who told me on our first conversation that he’s nobody, why would anyone be interested in his story, was getting recognized there by the ballet fans of New York City,” said Lin. “That was one of the high points of this whole journey, seeing George quietly but happily receiving their attention as he should because he’s a pioneer. This is lost history of the first Asian American male dancers in the ballet world.”

(Editor’s note: To learn more about this documentary, visit tentimesbetterfilm.com.)

This article was made possible by the Harry K. Honda Memorial Journalism Fund, which was established by JACL Redress Strategist Grant Ujifusa.

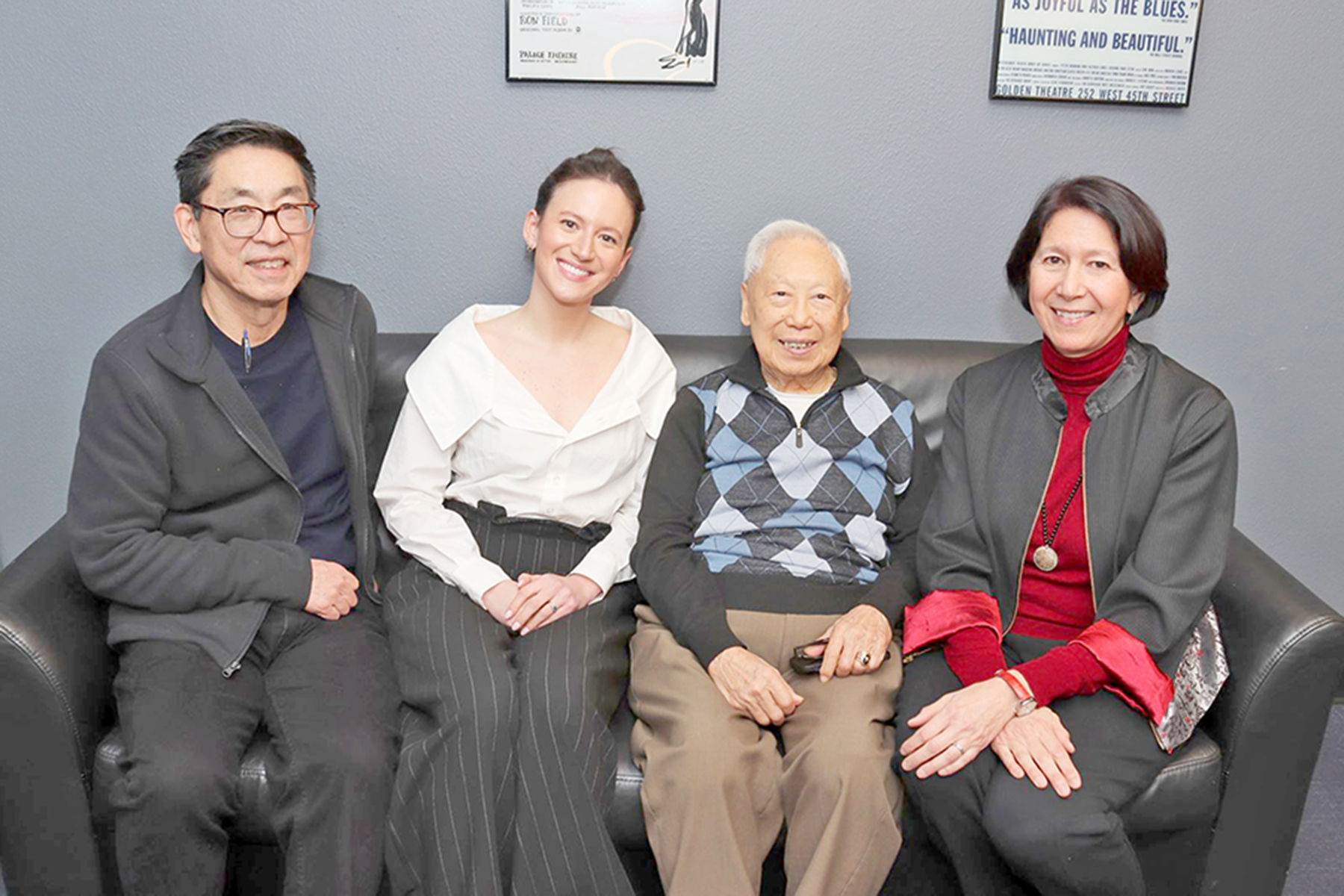

George Lee (pictured third from left) with producers (from left) Jon Funabiki, Cory Lin Stieg and Jennifer Lin. (Photo: Petalina Prods.)