The Riverside Unified School District

honors Issei immigrants and their descendants.

By George Toshio Johnston, Senior Editor

This fall when students enter the campus of their elementary school at 700 Highlander Dr. in Riverside, Calif., they will be stepping into both the past and future.

Students will be greeted by new Harada Elementary School floormats. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Although the 700 or so kindergarten through sixth-grade students will still be Hornets — the school’s mascot since opening in fall 1958 — they’ll no longer be proud Highlander Hornets.

They will be proud Harada Hornets.

In a ceremony that took place on May 1, a beautifully sunny Southern California day, the Riverside Unified School District Board of Education put into effect a unanimous decision to rename the Highlander Elementary School after the city’s own storied Harada family.

RUSD Board of Education member Dale Kinnear (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

“The significance of the name extends beyond the confines of our school district,” said RUSD Board of Education President Dale Kinnear. “Embracing the Harada name sends a powerful message to our students, to our community and the world at large, a message of unity, of empathy and solidarity. Riverside Unified School District has its very own Harada Elementary School. Sounds pretty good.”

Interestingly, it’s not the sole Harada Elementary School — some 16 miles away, also in Riverside County, in the town of Eastvale, Calif., there’s another Harada Elementary School (Home of the Dragons). Nevertheless, the rebranding of this Harada Elementary School remains significant because it’s an acknowledgement of how the Harada family took on existing laws and attitudes of the past that denied them the rights and privileges enjoyed by others in America, citizens and noncitizens alike.

Approval by the RUSD Board of Education to rename the school dates to June 29, 2023 — but the saga of the Haradas of Riverside dates back nearly 120 years, when immigrants Jukichi and Ken Harada and their son, Masaatsu, arrived in Riverside in 1905 from Japan. (See sidebar below for details.)

Riverside Unified School District Chief of Staff Neician Thaxton (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Under the guidance of master of ceremonies Neician Thaxton, RUSD chief of staff, the ceremony began with taiko drumming from four members of Riverside-based TaikoMix, followed by the Pledge of Allegiance, led by Kimberly Harada, a fourth-generation member of the Harada family.

Harada Elementary School Principal Andrea Sullivan (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Principal Andrea Sullivan, noting that hers was the first City of Riverside school to be named after an Asian American family, praised the RUSD’s decision as a “beacon of progress and unity in our community” that “not only honors the remarkable legacy of the Harada family, but also reflects our commitment to diversity, inclusion and equity and education.”

“Just as the Harada family fought tirelessly for the rights of their children to live free from discrimination, we are committed to providing every student at Harada Elementary School with a safe, nurturing and inclusive learning environment where they can thrive academically, socially and emotionally,” Sullivan said.

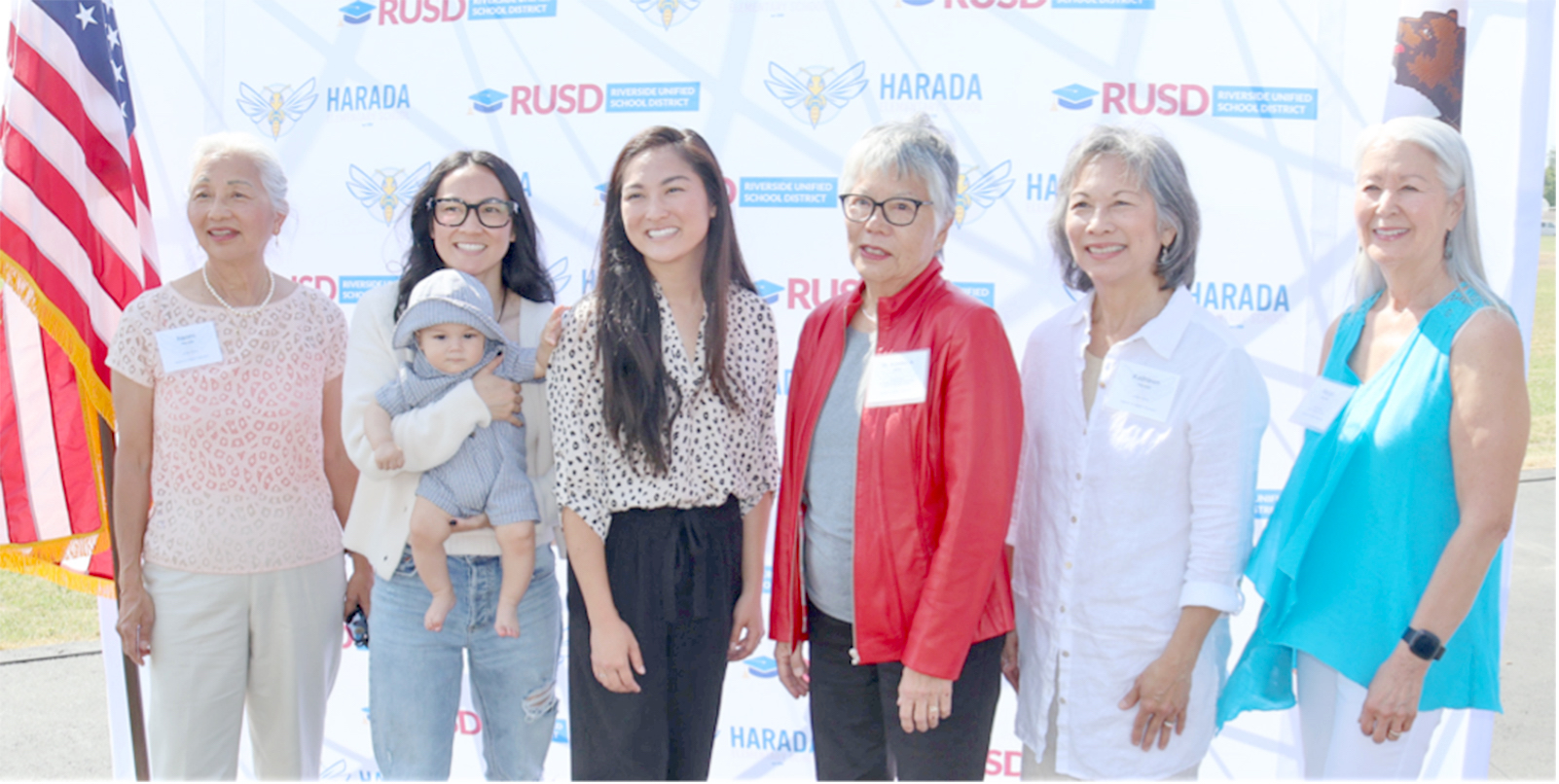

From left: Naomi Harada, Allison Harada, Alec Harada, Kimberly Harada, Kimiko Harada Klein, Kathleen Harada and Margo Brower (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

In addition to Kimberly Harada, other family members present for the ceremony were Margo Brower, Kathleen Harada, Allison Harada and her infant son, Alec Harada, Naomi Harada and Dr. Kimiko Harada Klein.

From left, Riverside Unified School District Board of Education members Dr. Angelo Farooq, Brent Lee, Dr. Noemi Hernandez Alexander, Superintendent Renee Hill, RUSD board members Tom Hunt and Dale Kinnear (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Also present were the other four members of the RUSD Board of Education, Dr. Noemi Hernandez Alexander (board clerk), Dr. Angelo Farooq, Tom Hunt (board VP) and Brent Lee, as well as Renee Hill, RUSD superintendent. Thaxton also recognized other distinguished attendees, including former state Assemblymember Jose Medina, District Director Desiree Wroten representing Rep. Mark Takano (D-Calif.), retired Riverside County Superior Court Judge Jackson Lucky and Riverside City Manager Mike Futrell, representing Mayor Patricia Lock Dawson.

TaikoMix members, from left, Terry Nguyen, Alysse Itatani, Donovan Reid and Sean Choi (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

In his remarks, Hunt, referring to Kimberly Harada’s role in leading the gathering in reciting the Pledge of Allegiance, spoke admiringly of the resilience and perseverance of the Haradas in the face of the discrimination they had faced decades earlier. “Liberty and justice for all — they weren’t receiving that,” he said, noting that they also would in the early 1940s be “forced in internment camps.”

“With a partnership with Harada House, for decades to come in school they’ll learn who they were, what they went through,” said Hunt, who also stated that in 1965, Riverside was the largest school district in the nation to voluntarily desegregate its schools.

Naomi Harada speaks on behalf of the Harada family during the renaming ceremony for Harada Elementary School on May 1 in Riverside, Calif. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Speaking on behalf of the Harada family was Naomi Harada, whose father was the late Dr. Harold Harada, DDS, a 442nd vet, the youngest son of Jukichi and Ken Harada who, incidentally, was born in the Harada House. “Harada Hornets. I really like that,” she said. “Haradas do have a lot of sting in them,” getting laughs from the audience.

Waxing serious, Harada noted the incredulity she felt from Riverside Unified School District and community members coming together in 2024 to “honor my grandparents, our great-grandparents and our great-great-grandparents, Jukichi and Ken Harada, by bestowing the school with their name.” The honor was extra special because Jukichi Harada had been trained to be a schoolteacher in Japan. “My grandparents were strong advocates for education.”

Part of that incredulity no doubt came from the struggles her grandparents faced. Jukichi Harada was an ardent believer in American ideals — he operated a restaurant named for George Washington — but was barred from becoming a naturalized U.S. citizen by the laws of his era. When he bought a home on Lemon Street in 1915 that would later become known as Harada House, he was again barred by the laws of the time from owning the property, so he attempted a workaround — putting ownership in the names of his American-born children.

The Harada Hope Garden on the campus of Harada Elementary School (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

According to a 1991 Los Angeles Times article, not only did 60 local families sign a petition demanding the Haradas be evicted, the state of California also attempted to confiscate the property, asserting that the purchase was actually an Alien Land Law violation.

During WWII, when the government removed more than 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast and placed them in concentration camps, Jukichi and Ken Harada would die while incarcerated at Utah’s Topaz War Relocation Authority Center.

“America, you’ve come a long way,” Naomi Harada said. “However, we cannot forget the hardships of our forebears. We must teach and educate our children to continue to reinforce our civil rights. A heartfelt thank you to all of you.”

Members of the Harada family and everyone present for the May 1 renaming ceremony gather for a group photo on the campus of the newly renamed Harada Elementary School. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Who Were the Haradas and What Is Harada House?

For those unaware of the history that led to the renaming of Riverside, Calif.’s Harada Elementary School, the first question might be: For whom was the school renamed? A second question: What is Harada House?

To answer both questions, one must revisit the year 1905, when Jukichi and Ken Harada and their son, Masaatsu, arrived in Riverside from Japan. Within a few years, Jukichi and Ken Harada wanted to buy a house of their own for their growing family after their 5-year-old son, Tadao, died of diphtheria he had contracted while in the boarding house in which they had been living.

There were major obstacles to the Haradas’ “pursuit of happiness,” which in this instance meant buying a home. One was the California Alien Land Law of 1913, which prevented “aliens ineligible for citizenship” from owning property. Although the law also affected other immigrants with East Asian and South Asian roots, it was aimed primarily at immigrant Japanese.

File photo of the Harada House, 3356 Lemon St. in Riverside, Calif.

The other major obstacles: the Nationality Act of 1790, which only allowed naturalized citizenship to “any alien, being a free white person,” and the post-Civil War Naturalization Act of 1870, which restricted citizenship to “free white” people or those of “African nativity and descent.”

That situation meant the Haradas — and other Issei — were simultaneously proscribed from owning land because they were aliens ineligible for citizenship but also precluded from becoming naturalized U.S. citizens. What to do?

Enter the 14th Amendment. Ratified in 1868, it reads: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

This meant that while the Haradas couldn’t own their home, they could purchase it in the names of their American-born children: Mine, Sumi and Yoshizo — and that was what they did.

Riverside denizens and the state of California, however, not appreciating the clever circumvention of institutional racism, decided to challenge what Jukichi Harada had done. The case was The People of State of California vs. Jukichi Harada, Mine Harada, Sumi Harada and Yoshizo Harada.

The National Park Service summarized the outcome of the case as follows: “On Sept. 14, 1918, Judge Hugh Craig of the Riverside Superior Court ruled in favor of the Harada children.”

While it was a mixed decision — Craig “upheld the Alien Land Law of 1913”— Jukichi Harada’s tactic proved to be victorious. Because the Harada children were born in the U.S., they were citizens protected under the 14th Amendment — and thus able to own property.

In his ruling, Craig wrote: “The political rights of American citizens are the same, no matter what their heritage.” (In 1952, not only was the California Alien Land Law struck down by the California Supreme Court, but also the McCarran-Walter Act allowed Japanese nationals and other Asian immigrants to become naturalized U.S. citizens.)

As for the Harada House, Sumi Harada moved back after WWII incarceration, living there until 1998. When she died in 2000 at 90, her brother, Harold Harada, inherited the property. After his death in 2003 at 80, his heirs transferred ownership to the City of Riverside, with the Riverside Metropolitan Museum serving as the home’s steward.

Today, the Harada House is a museum, having received National Historic Landmark status in 1990. In 2020, Harada House was included in the National Trust for Historic Preservation annual list of 11 Most Endangered Historic Places in America (see “The Harada House: Strengthening Our Community Through Action,” Pacific Citizen, Sept. 11, 2020, tinyurl.com/mr33hk9k). In 2022, it received state landmark status as California Historical Landmark No. 1060.

To learn more about Harada House, visit tinyurl.com/2t258mds. To learn more about the Harada House Foundation, visit tinyurl.com/mvaa6hnu.