A new Eric Muller book examines the perspective of WRA attorneys who ran the camps.

By Gil Asakawa, P.C. Contributor

Eric Muller’s new book examines the perspective of WRA attorneys who juggled with their sense of justice and civil rights against the requirements of their jobs during World War II. (Photo: Gil Asakawa)

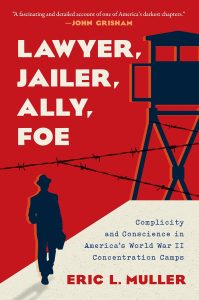

Eric Muller is a professor and historian who has authored a series of books about the Japanese American incarceration experience. But his latest book, “: Complicity and Conscience in America’s World War II Concentration Camps” (University of North Carolina Press, 304 pp., hardcover ISBN: 978-1-4696-7397-4, SRP: $30), chronicles that experience from a different perspective: through the men who worked for the War Relocation Authority during World War II as the project attorneys within the concentration camps whose job was to help run them for the U.S. government and at the same time represent the Japanese American prisoners in legal disputes, which could lead to conflicts of interest or, perhaps, conflicts of conscience.

Muller discussed the book and its unique approach in a recent virtual presentation for Densho, moderated by Densho Content Director Brian Niiya. He explained in the opening why the book isn’t a typical look at wartime incarceration and cited a quote by historian Timothy Snyder from his book “Bloodlands,” which looked at millions of people murdered by both Nazi Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union in Central Europe before and during WWII.

“Lawyer, Jailer, Ally, Foe” author Eric Muller (top) speaks about his new book with Densho’s Brian Niiya in a recent virtual meeting. (Photo: Gil Asakawa)

“It’s easy to sanctify policies or identities by the suffering of victims. It’s less appealing but morally more urgent to understand the actions of the perpetrators because the moral danger is never that one might become a victim, but rather, the moral danger is that one might become a perpetrator or a bystander,” Muller paraphrased. “This book explores the question of what it was that led rather ordinary, and I would say, generally decent men, three men in particular in this account, to lend their professional energies to the work of the War Relocation Authority.”

Muller is an award-winning professor in the University of North Carolina’s law school whose previous books include “Colors of Confinement: Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in World War II,” “American Inquisition: The Hunt for Japanese American Disloyalty in World War II” and “Free to Die for their Country: The Story of the Japanese American Draft Resisters in World War II.”

He also launched a podcast for JA stories, writes a blog and has written articles for publications and websites including Densho about Japanese American history. In addition, he curated the award-winning core historical exhibit at the Heart Mountain camp in Wyoming and serves on the board of the National Japanese American Memorial Foundation.

Muller became interested in the JA incarceration when he was an assistant professor at the University of Wyoming College of Law and learned about the Nisei draft resisters. He was introduced to Jerry Housel, who had been the project attorney at Heart Mountain. Housel was one of the three men Muller focuses on in the book, along with Jim Terry, who was at Gila River in Arizona, and Ted Haas, the camp lawyer at Poston in Arizona. They all worked previously for President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal agencies during the Great Depression, and Haas in particular, who was Jewish, worked for the Office of Indian Affairs to, as Muller said, “Do good work on behalf of a beleaguered American minority.”

This liberal base wasn’t unusual. “The War Relocation Authority was a civilian agency that was led by progressives,” Muller said. “And that’s a hard thing for us to get our minds around when we think about what the agency actually did, but when you think about the agency in the context of its times, it was easily the most progressive group of government officials that you were likely to find on the question of the removal and imprisonment of Japanese Americans.”

The irony is that these men and many other people who worked for the WRA had to juggle their sense of justice and civil rights against the requirements of their jobs. They had the freedom to do their work independently, so, as Muller pointed out in his talk, one allowed a barbed-wire fence to be raised around the barracks at his camp while another tried to protest the decision (he lost).

Muller wrote the book in almost a novelist’s style, with dialogue and descriptive scenes. He took his license to tell these stories in a pseudo-fictional voice because it could connect better with readers and because he based every detail on historical fact, not fiction. His sources were the voluminous written reports that every project attorney had to file with the WRA every other week. The reports were often 10 pages long and were detailed and written in a personal voice, so Muller could get a sense of each man’s state of mind.

Housel, who Muller met late in life, regretted working for the WRA, Muller said. Even Terry, who is described as an irascible character, wrote in his final report to the WRA that he thought the camps were “not a clear and absolute necessity from the outset.”

“So, I think you can see the sort of the paradox that I’m trying to explore through these men,” Muller told the audience. “How is it that somebody with views like this, nonetheless ends up being part of the enterprise that helps to operate it?”

Because the source materials for the book were hundreds of pages of letters from the lawyers, Muller said as his final point, “You get a different window into camp life than we often get from other kinds of documentary evidence. Think about it. These were law offices. This is where people went when they were struggling with difficult moments in life, whether it be child custody disputes or mental illness that required institutionalization or whether it perhaps involved petty theft or in violence between one inmate and another inmate or marital problems.

“The point I’m making — it’s not common that most people who, when they sit down for an oral history, they don’t say, ‘Oh, right, camp, that was the place where I cheated on my wife.’ That’s not the kind of thing that people tend to talk about. But those things happened. And they’re important evidence of the kinds of pressures that the prison population was under.”

Muller’s future projects include a look at the Japanese Evacuation Claims Act of 1948, which got some compensation for former incarcerees, and then eventually, a complete history of the War Relocation Authority.

Author Eric Muller at the Japanese American National Museum’s Tateuchi Democracy Forum on Oct. 7, 2023. He was in attendance to discuss his new book, “Lawyer, Jailer, Ally, Foe.” (Photo: Gil Asakawa)

But his audience for the Densho talk might just be hungry for more stories from his research into the lawyers who worked in the camps

To view the recording of this event, visit tinyurl.com/3r6mn6hu.

(This article was made possible by the Harry K. Honda Memorial Journalism Fund, which was established by JACL Redress Strategist Grant Ujifusa.)