Itami is pictured (back row, third from left) with members of the Operational Intelligence Section at Camp Ritchie.

Bringing to light a life cut short following Itami’s

decorated service in the Military Intelligence Service.

By Beverley Driver Eddy

David Akira Itami devoted his life to service to the United States. Why, then, is he forgotten in this country and honored in Japan? His biography reveals the complex issues — then and now — that have governed his case.

Itami was one of approximately 6,000 Japanese Americans (Nisei) who served in the Military Intelligence Service of the U.S. Army during World War II. His work was especially valued because he was a Kibei Nisei — one of those Japanese Americans who spent several years of their childhood living in Japan.

He was born in Oakland, Calif., in 1911 but was sent, just before his second birthday, to live with his paternal aunt in Kajiki, a small coastal town in Kagoshima Prefecture. After attending the local grade school, he went on to study at the Daito Bunka Gakuin (Academy of Greater East Asian Culture) in Tokyo. But because of his mother’s failing health, he had to return to the States in 1931. He was 19 years old.

Itami’s life now took a very different direction. His first duty was to learn English. Fortunately, he was able to do this remarkably quickly.

After taking a job at a salmon cannery in Alaska, where he exercised his first leadership role by helping the Asian immigrant community negotiate their summer wages, he returned to California and settled in Los Angeles. It did not take him long to transition to a position of influence in the Japanese American community.

First, he taught Japanese language classes at the Nishi Hongwanji Buddhist Temple and took courses at Los Angeles City College. Then, in 1934, he found employment on the editorial staff of the bilingual newspaper Kashu Mainichi Shinbun/The Japan-California Daily News.

Itami renounced his Japanese citizenship in 1935, but he never renounced his Asian heritage. He helped establish a Japanese American literary magazine, worked on educational programming for the Kibei division of the JACL and in 1940 became editor of a news magazine written by and for Kibei.

Pictured (from left) are monitor Itami, interpreter Tomio Mori and a court reporter at the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal.

It was his dream that the Kibei Nisei could provide a bridge between Japan and the United States. But he alienated himself from leftist members of the Kibei Nisei community when he wrote that the United States had more to fear from Russia than Japan. This alienation turned to open hostility in October 1940, when Itami used his authority as vp of JACL’s Kibei Division to expel some of its Communist members.

He continued to be the acknowledged head of this division, however, even when the JACL leadership changed and its new and powerful anti-Axis Committee demanded that Kibei and Issei sever all contact with Japan. Things escalated when Japan launched its surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. On the evening of Dec. 7, more than 5,500 community leaders were rounded up and sent to detention centers.

Itami now had to tread a careful line at Kashu Mainichi, since the JACL’s anti-Axis Committee was monitoring it and other Japanese American newspapers for “fascist tendencies.” He immediately dropped all favorable commentaries about Japan and appealed in the paper, instead, to American patriotism.

Then, on Feb. 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. In a final editorial before publication of Kashu Mainichi was suspended, Itami and his colleagues urged all Nisei to comply with EO 9066.

At the same time, Itami wrote a letter to Time Magazine, in which he gave a major reason for supporting the resettlement: “We Nisei on the California coast certainly do not wish to be looked upon as potential saboteurs or fifth columnists. Neither do we have any desire to be charged responsible if and when any single bomb is dropped here.”

Two days after Kashu Mainichi suspended publication, Itami was among 85 Los Angeles Japanese Americans to join an advance work party that helped prepare for the arrival of detainees at the Owens Valley Reception Center in Manzanar, Calif. Thousands would enter the camp in the days that followed, including Itami’s wife and 4-year-old daughter.

There, Itami served as executive secretary of the block leaders council and translated and transcribed the camp newspaper into Japanese.

He continued to believe that it was the duty of all loyal Nisei to accept their forced incarceration as part of their contribution to the American war effort. That May, he wrote a second letter to Time Magazine, praising Manzanar and saying that conditions there were “just about the best that we can expect under the circumstances.” He declared that the federal officials who served as camp administrators were “very courteous and considerate toward all of us” and that “under the snow-covered High Sierra mountains our life is just wonderful. . . .”

But Itami remained at the camp only seven months. In October, Col. Kai Rasmussen, commander of the Military Intelligence Service Language School at Camp Savage, Minn., came to Manzanar to recruit Japanese language instructors. He immediately hired Itami and two other Nisei as civilian instructors; the three men left Manzanar as the very first volunteers from relocation centers to be recruited by the U.S. military. Itami’s departure was noted with disfavor by two opposing factions at the camp: hostile anti-Axis JACL members and a small, but violent, pro-Japan faction.

The language program at Camp Savage was a daunting one. Japanese linguists were needed to serve the Army. Itami taught there until March 1944. Then, he enlisted in the U.S. Army and was sent to Washington, D.C., to work for the MIS, translating and deciphering Japanese codes.

The MIS faced a unique situation in the war with Japan. The branch history of the Pacific Military Intelligence Research Section, or PACMIRS, pointed out that the Japanese entrusted much more military information to written records than was usual for a country at war. Thus, a plan was developed for the establishment of PACMIRS as a centralized translating agency, and it was brought to Camp Ritchie, Md., in September 1944.

Even before his arrival at Camp Ritchie, Itami had made himself indispensable by starting to file and index Japanese reference material in Washington; at Ritchie, he was assigned to the Operational Intelligence Section, or Japanese reference library. The official branch history of PACMIRS acknowledged Itami’s work by pointing out that “Sgt. Itami’s research in the field of Japanese official publications was made the basis of several Special Projects ….” He was the only Nisei and the only noncommissioned officer to be mentioned by name in this official history.

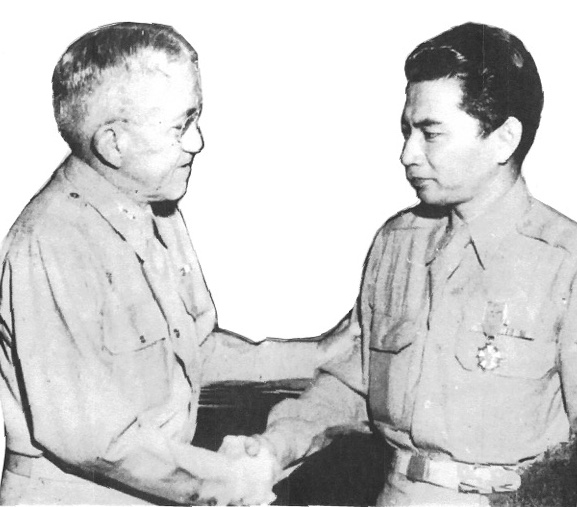

Maj. Gen. Myron C. Cramer congratulates Itami upon his receipt of the Legion of Merit in August 1946.

His work was rewarded in August 1946, when he received the Legion of Merit for having “assembled a reference library of more than 4,000 Japanese official orders, manuals and regulations, indexed under some 25,000 subject headings.” Furthermore, “exercising a keen knowledge of the Japanese language and military affairs, Itami … extracted from his library much original data on Japanese high command orders, army technical research institutes and recruiting and replacement systems.” When asked about the honor, Itami’s wife replied: “I am so grateful he has proved himself. When people said, ‘You are Kibei. We can’t trust you,’ it hurt him as if he had been called a traitor. Now they know.”

Itami was discharged from the Army on April 10, 1946, but he remained a War Department civilian employee. That April, he and three other Kibei from the Allied Power’s Translation and Interpretation Section were assigned to monitor the work of the Japanese interpreters at the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal. These trials did not adjourn until Nov. 12, 1948.

Itami was particularly adept at explaining subtle distinctions in language. At the trials, he stepped in not only to correct language misperceptions, but also to silence the prosecutor when he interrupted the testimony of Japan’s former wartime leader, Gen. Hideki Tojo.

Once the intensive labor of the trials was over, however, Itami fell into a deep depression. On Dec. 26, 1950, he died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound. He was 39 years old.

A poster for the 2019 Japanese TV film based on Toyoko Yamasaki’s fictionalized account of David Akira Itami’s life

Itami might have been forgotten as just another war casualty — until novelist Toyoko Yamasaki took an interest in his case and published his story in 1983 in the novel “Futatsu No Sokoku” (“Two Homelands”). (An abridged English translation appeared in 2008.) It was turned into a yearlong TV series in 1984 and a two-part TV film in 2019.

Yamasaki portrayed her hero’s disillusionment with America’s conduct of the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal and America’s continued anti-Japanese fervor as major reasons for his suicide. Itami’s daughter, Michi, who was 12 at the time of her father’s death, offered another reason for his depression. “I think that being a Kibei . . . was difficult for him, as he did not belong to any group,” she said. “Nisei did not trust Kibei because they were so different from themselves. Also, he was alienated from other Kibei because he was too intelligent to believe the propaganda of the Japanese military government at the time.”

Today, it is Japan, and not America, that honors Itami. In Kijiki, a memorial was erected at the site of his childhood home. And the college he had attended as a young man named a large assembly hall in his honor.

The Nisei in America, however, successfully banned the 1984 film “Two Homelands” from being shown in the continental United States because they were deep into negotiations for redress and reparations for their forced internment during the war. As a result, they had — and continue to have — little interest in celebrating a Kibei who proclaimed their voluntary internment an act of American patriotism, despite his spectacular wartime achievements.

Beverley Driver Eddy is a retired professor at Dickenson College in Carlisle, Pa.