Susumu Ito, in the red, white and blue garrison cap and displaying his Congressional Gold Medal,

is flanked by members of the House and Senate at the Nov. 2, 2011, ceremony at the nation’s capitol. (Photo: Courtesy of JAVA)

Ten years later, a look back to when the U.S. paid tribute to Nisei WWII veterans.

By P.C. Staff

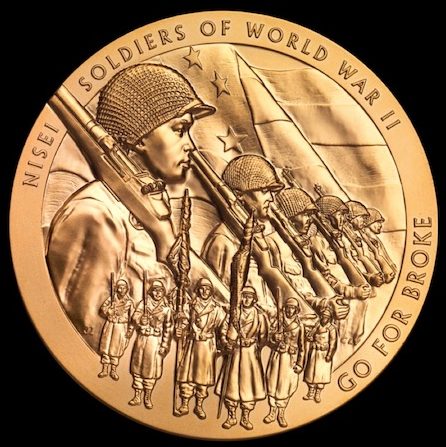

Obverse of the Congressional Gold Medal honoring Nisei veterans of WWII.

November 2021 marks the 10th anniversary of highest recognition among the many marks of distinction achieved by the extraordinary service of second-generation Japanese Americans who served in the United States Armed Forces during World War II: the Congressional Gold Medal.

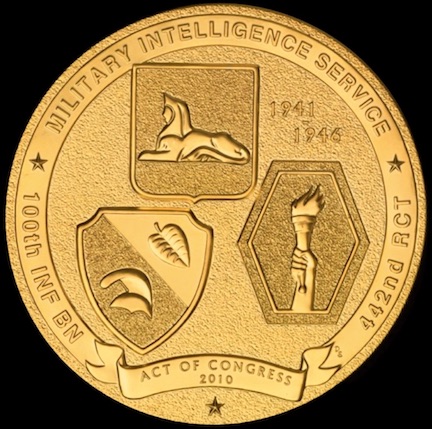

With Veterans Day 2021 coinciding with that 10th anniversary, when the United States Congress honored collectively the Nisei members of the Military Intelligence Service, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and the 100th Battalion, the Pacific Citizen looks back at how this recognition came to pass.

Following are the recollections of a few of the many individuals from several organizations that worked together to turn a vision of kansha and reconciliation for those men, still-living and deceased, into a medallion of honor, an heirloom that validated for those still-living veterans the sacrifices, physical injuries and psychological traumas that accompanied serving their nation.

Nov. 2, 2011, was when this nation embraced the now-elderly Japanese American soldiers, who held firm to their steadfast belief in the promise of freedom, justice and equality for all, decades after America initially rejected them as enemy aliens and, for those who lived on the Pacific Coast, incarcerated them and their families.

Most of those men who were fortunate to be a part of that ceremony a decade ago have since passed, for not even the greatest human warrior may live forever. The recollections and images of that day and what they accomplished to earn that commendation, however, can be passed to their American heirs of all backgrounds, creeds and beliefs. It is a tale for the ages.

President Obama is feted on Oct. 5, 2010, by veterans, politicians and community leaders after enacting S. 1055, opening the door to recognizing the military service and contributions to WWII by Japanese Americans. (See Pacific Citizen, Oct. 15-Nov. 4, 2010.)

(Photo: Official White House Photo: Pete Souza)

Revisiting President Obama’s Oct. 5, 2010, authorization of the bill to award the Congressional Gold Medal on Nov. 2, 2011, to American WWII veterans of Japanese heritage, it might appear that those events were obvious, straightforward courses of action, akin to a fait accompli.

In a word, no.

National Veterans Network Executive Director Christine Sato-Yamazaki told the Pacific Citizen, “I think most of the country does not know what it took to get the Congressional Gold Medal passed in Congress.”

Speaker of the House John Boehner (left) presents MIS vet Grant Ichikawa his Congressional Gold Medal on Nov. 2, 2011. (Photo: Courtesy of Jean Shiraki)

Despite the well-documented and, to Japanese Americans at least, well-known WWII exploits of those Nisei who served in combat roles in the European Theater and intelligence roles in the Pacific Theater, it turned out that there were many members of Congress who needed to be educated about what they evidently did not learn in school or via popular culture.

That history in question occurred during that greatest of wars, when Americans whose ancestors hailed from Asia — Japan, to be specific in this scenario — served the U.S. as ably, if not more so, than Americans with European roots.

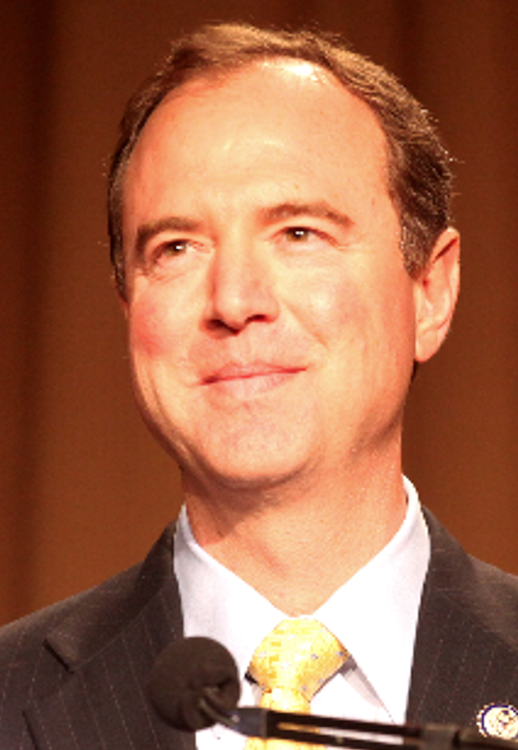

Rep. Adam Schiff addresses the audience during the Nov. 2, 2011, banquet. (Photo: Joe Shymanski)

With help in Congress from Rep. Adam Schiff (D-Calif.) and then-Sen. Barbara Boxer (D-Calif.), the Japanese American community commenced a roughly two-year long campaign to educate, cajole and compel members of Congress in both houses and all political parties to unite in favor of honoring the Nisei soldiers with a Congressional Gold Medal.

As it turned out, convincing the House of Representatives to pass a bill to award the Nisei veterans was the easier task, thanks to Schiff’s leadership in the House. On the Senate side, things were a bit more difficult.

MIS vet Paul Bannai scrutinizes the program at the gala banquet. (Photo: Joe Shymanski)

Although Sen. Daniel K. Inouye (D-Hawaii) was held in high esteem within the Senate, having been awarded the Medal of Honor as a member of the 100th Battalion, he did not take a visible role in pushing for Congressional Gold Medal recognition for his fellow Nisei veterans, lest his advocacy seem self-serving.

According to Floyd Mori, who in 2010 was the JACL’s national director, it was Boxer, “having represented many of the Japanese Americans in California, knew of the story and was very strong in advocating,” who advocated for the Congressional Gold Medal on the Senate side.

George Sakato (Photo: Joe Shymanski)

Mori also credited Sen. Robert Bennett (R-Utah), who was “very familiar with the Japanese American story,” including that of 442nd veteran (and Medal of Honor awardee) George Sakato, who Mori said was inducted into the Army from Salt Lake City.

Having Inouye, Boxer and Bennett — and maybe 30-35 other senators —committed to “the Boxer bill,” aka S. 1055, was, however, not enough; it would need 67 bipartisan votes before it could move forward to the White House.

Different strategies were needed for different states. Decisions on dividing the labor were needed. Time was of the essence, due to the advanced ages of those still-living veterans, not to mention the looming summer recess.

Fortunately, there were two elderly vets and two much-younger people up to the task of helping to persuade senators and their staffs on the importance of passing the bill.

The elders were Grant Ichikawa and Terry Shima. The “youngsters” were winners of the JACL’s Norman Y. Mineta Fellowship and Daniel K. Inouye Fellowship: Phillip Ozaki and Jean Shiraki, respectively, both of whom served on Mori’s staff.

(From left) Jean Shiraki, Terry Shima, Grant Ichikawa and Phillip Ozaki split into two teams to visit 50 U.S. senator’s offices to persuade them to support a bill to award Nisei WWII vets the Congressional Gold Medal. (Photo: Courtesy of Phillip Ozaki)

Sadly, Grant Ichikawa died in 2017. But Shima, who turns 99 on Jan. 20, Shiraki and Ozaki remember well the work it took to convince senators on the import of passing the bill.

A decade after the Congressional Gold Medal ceremony, Shiraki is a practicing family physician in San Diego; Ozaki, meantime, is a JACL staffer with the title of development director and before that, he served as membership and program manager.

Floyd Mori: As we moved into the campaign for the Congressional Gold Medal, one of the important aspects of that was we, as JACL, made an effort to visit many of the offices of the senators, and we took along with us WWII veterans Terry Shima, who was in the 442nd, and Grant Ichikawa, who was MIS.

Reverse of the Congressional Gold Medal awarded to Nisei WWII vets in 2011.

To take these real-life veterans of WWII office to office . . . how could the senator refuse to support the bill when there are two veterans like those two explaining the role of Japanese Americans and what they did during WWII?

Phillip Ozaki: I was 23, fresh out of college, first time doing this, but I felt really good about it because I really believed that my grandfather (Sam Ozaki) and the 4-4-2 were deserving of the Congressional Gold Medal.

Christine Sato-Yamazaki: There was a period in our campaign where it stalled in the Senate. Floyd took Terry Shima and Grant Ichikawa, and they walked the floor of Congress . . . their contribution was significant.

Jean Shiraki: We both were tasked to . . . start the momentum again for the Senate Bill 1055. . . . There already had been some core co-sponsors of the bill, but it kind of had been a little stagnant in terms of having enough senator co-sponsors.

Ozaki: We did what I called the “bull rush” strategy. Since 50 senators had signed on, we had 15 senate visits to make. So, we split up into teams. I took Grant, and Jean took Terry, and then we had a list of 25 senators each to visit. And so, in one day, the four of us visited half the Senate.

Shiraki: I just remember Philip and I laughed because if we were very exhausted, then we could only imagine how exhausted Terry Shima and Grant Ichikawa were that day.

Terry Shima, 442nd RCT (Photo: Joe Shymanski)

Terry Shima: Shiraki and Ozaki did all the planning, contacted and made appointments, briefed the senator’s staff and requested them to have their senators sign on to the Boxer bill. They then asked Grant and me to explain what the Nisei did in Europe and the Asia Pacific Theater.

Shiraki: We split 50 offices. . . . Eventually, though, we did tag on about 20 more offices afterwards just like to be fully complete because we really wanted a two-thirds majority of Senate co-sponsors for the bill. . . . I think it was pretty effective in really getting the momentum back. . . . I think, obviously, what really helps is having a personal story, and that’s what Terry and Grant brought.

Shima: Initially, senators were reluctant to sign on, preferring to wait and see how other senators responded. We were told this is common practice among senators who did not have pressure from their constituents and the bill’s sponsor. This motivated us to work harder — to use all options available to us.

One wrinkle that occurred early in the process cropped up when it was learned that the MIS were not part of Schiff’s original version of the bill.

Shima: On Jan. 14, 2009, I received a call from Bill Takakoshi, who was doing his firm’s business in Capitol Hill. Bill said Congressman Adam Schiff’s bill to award the Congressional Gold Medal to the 100th Battalion and the 442nd RCT was being voted that day. Takakoshi then introduced me to Aaron Baird, Schiff’s staff officer.

I asked whether the MIS was included in the bill, and Baird said no. When he was told why MIS should be included, he invited me to come to his office as soon as possible to meet Schiff.

When the inclusion of the MIS was explained to Schiff, he agreed, said it was too late to include in his bill, which was being voted on that day, and suggested an amendment be included in Sen. Boxer’s bill. I maintained contact with Schiff’s office until the bill, which contained the MIS, had passed the House.

The hard, collective work of visiting different senators’ offices did, in fact, pay off. S. 1055 passed through the Senate, with 73 voting in favor: 49 Democrats, 22 Republicans, one Independent and one Independent Democrat. The president signed it on Oct. 5, 2010.

Mitsuo Kunihiro shares a grin. (Photo: Joe Shymanski)

A little more than a year later, on Oct. 31, 2011, registration began for a three-day program that included the Congressional Gold Medal presentations at the United States Capitol, a gala banquet at the Washington, D.C., Hilton Hotel that drew more than 2,500 people and visits to the WWII Memorial and National Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism.

On the morning of Nov. 1, 2011, the program commenced with a tribute to the veterans of WWII in the Washington Hilton’s Columbia Hall, followed by a visit for veterans only to the WWII Memorial.

On the cold morning of Nov. 2 was the Congressional Gold Medal Ceremony, held at the Capitol. That evening was the gala dinner titled “Tribute to 100th, 442nd and MIS.” And, on Nov. 3, this last large muster of old soldiers took part in the Remembrance Ceremony at the National Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism, attended only by the members of KIA families.

Mori: The speaker [of the House] at the time was John Boehner. And he spoke very eloquently about the role of Japanese Americans at the ceremony. And, of course, on the Senate side, Sen. Inouye spoke. Harry Reid was the leader on the Senate side. So, there was a great bipartisan effort in recognizing the (Nisei) soldiers of WWII.

Darrell Kunitomi, a longtime Los Angeles Times employee, and Jon Kaji, who is running for a seat on the Torrance City Council next June, are sons of MIS vets Jack Kunitomi and Bruce Kaji. They relayed to the Pacific Citizen their recollections from 10 years ago.

Rose Ochi and MIS veteran Jack Kunitomi (Photo: Joe Shymanski)

Darrell Kunitomi: I recall a few incidents that stand out in my memory: Our dad meeting Sen. Daniel Inouye, taking pictures with him, smiling broadly at meeting the living legend that was the senator; visiting the WWII memorial with him, and taking a family portrait there; seeing him sitting with other vets, then he looked over at his neighbor for a moment, then said, “Is that you, Ard?” It was his old buddy from the MIS, Ardaven Kozono, who he hadn’t seen since they had served together.

MIS veteran Bruce Kaji in front of the U.S. Capitol in November 2011 (Photo: Courtesy of Jon Kaji)

Jon Kaji: All of the members got on a bus, which took us to the Capitol. We all cleared security and then were ushered into the assembly room for the ceremony.

Kunitomi: There was time to sit and chat with other Japanese Americans from around the country. And that was just wonderful. So many told of their dads and grandads service, many knew a lot, and some knew precious little. Yet, all were proud and grateful. It was moving to talk with someone and know that you shared very similar stories.

Kaji: As Bruce sat down with some of his friends from MIS, I think that take by the MIS members was a lot different than the 100th/442nd vets.

As I listened to them, I think the sense they got was, after the war, of course, the 100th/442nd, they’re recognized by President (Harry) Truman at the White House and had a ticker tape parade. But no one knew about the MIS.

But I think over the years, they felt kind of miffed that, well, what the 100th/442nd did was great and tremendous. A lot of the guys lost their lives or got wounded as a result. But there was a certain sense of competition.

And I think that event helped to equalize the recognition, among all the Nisei vets. I think for the MIS members that day, they were really, really happy.

On Nov. 2, the National Veterans Networks released an online video in conjunction with the 10th anniversary of the Congressional Gold Medal ceremony. It can be viewed at tinyurl.com/bb4ekskm.

To watch C-Span’s coverage of the 2011 Congressional Gold Medal presentations, visit tinyurl.com/y9erasj9.

To purchase any of Joe Shymanski’s photographs, visit https://joeshymanski.zenfolio.com/p373963016.

The Washington Hilton Hotel’s largest ballroom accommodated more than 2,500 guests who attended the gala dinner on Nov. 2. (Photo: Joe Shymanski)