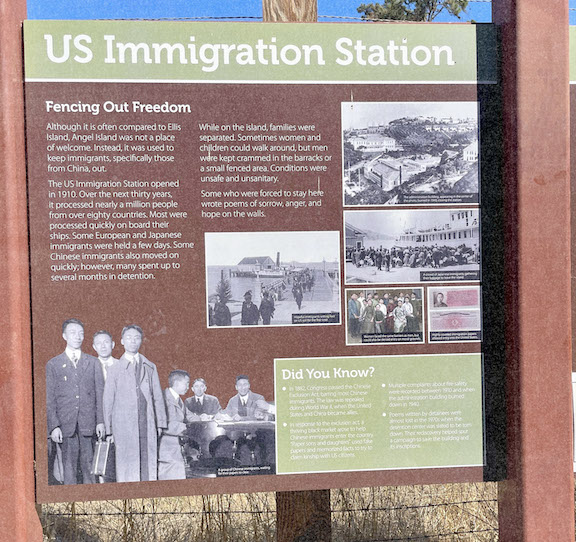

This cutout collage from historic photographs on display at the

Angel Island Immigration Station shows the different groups of immigrants who were detained there. (Photo: Emily Murase)

Pilgrims Unite at the Angel Island Immigration Station

and Retrace Life-Changing Steps Taken by their ancestors.

By Emily Murase, Contributor

What was a pleasant and gentle 35-minute ferry ride for the hundreds of Nikkei pilgrims who traveled to Angel Island on Oct. 5 was instead a harrowing and life-changing experience for their ancestors, Japanese immigrants who undertook a three-week journey to the same destination from the Port of Yokohama, including stops in Hong Kong, Manila and Honolulu, more than a 100 years before.

Not far from its far-more-famous-sister Alcatraz Island, Angel Island sits in San Francisco Bay. While the Statue of Liberty on New York’s Ellis Island, completed in 1886, famously beckoned, “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free” to primarily European communities, the U.S. Congress enacted the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, severely restricting new Chinese immigration.

Rev. Masato Kawahatsu offers a blessing at the Angel Island Immigration Station Pilgrimage. (Photo: Mark Shigenaga)

The limited exception was Chinese family members of U.S. citizens who, then, suddenly proliferated through the use of “paper names,” an underground market of forged documents attesting to family connections to Chinese already settled in the U.S.

Exclusionary Immigration Station (Photo: Emily Murase)

Known as the “Guardian of the Western Gate” among staff who worked there, the Angel Island Immigration Station was built in 1910 with the express purpose to control the flow of immigrants primarily from Asia, according to the Angel Island Conservancy. The Angel Island Immigration Station was designed to interrogate, physically examine, approve and, in many cases, deport would-be immigrants to this country.

Between 1910 and 1940, the immigration station processed an estimated 85,000 Japanese pioneers and fortune-seekers, encouraged by the Japanese government, labor brokers and farmers seeking picture brides to start families.

Since 2014, the Nichi Bei Foundation, which publishes the Nichi Bei News in San Francisco Japantown, has partnered with the Angel Island State Park, the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation and the California Genealogical Society to host the Nikkei Angel Island Pilgrimage.

Notwithstanding the contrast with Ellis Island, Nichi Bei Foundation President Kenji Taguma has called Angel Island the “Plymouth Rock” for Japanese Americans.

Through five previous pilgrimages, more than 2,000 people have connected with the rich history of the Angel Island Immigration Station. This year’s event was held on Oct. 5 and featured bus transportation from Sacramento and San Jose, bringing about 250 attendees from throughout Northern California.

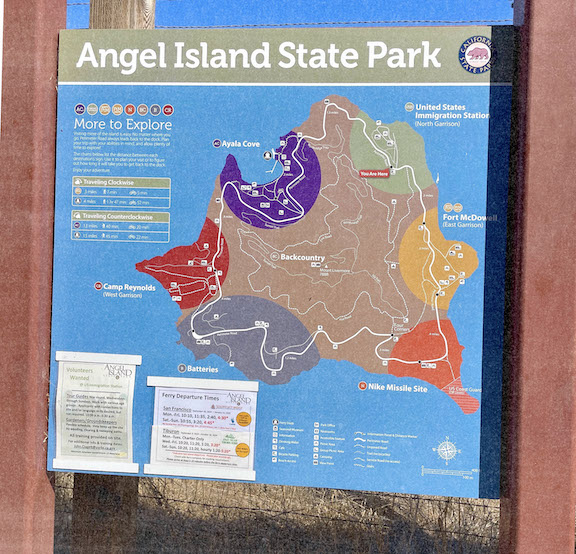

A map of Angel Island State Park (Photo: Emily Murase)

Roy and PJ Hirabayashi of TaikoPeace gave a performance to open the ceremony at the Angel Island Immigration Station. (Photos: Mark Shigenaga)

The ceremony at the Immigration Station opened joyously with a performance by TaikoPeace, a movement by PJ Hirabayashi to connect the energy of taiko with social justice, and Bonbu Stories, a new Asian American storytelling collaborative, under the mentorship of Hirabayashi. She, together with spouse Roy Hirabayashi, were among the founders of the pioneering San Jose Taiko Group in 1973.

Rev. Masato Kawahatsu of the San Francisco Konko Church, assisted by his spouse, Alice, performed a ritual blessing of the pilgrimage.

A longtime resident of San Francisco Japantown, Alice Kawahatsu recalled attending the very first pilgrimage in 2014. “I remember that there were over 500 people on that first pilgrimage. Everyone was so excited. Even though many of us grew up in and around the San Francisco Bay Area, many had never visited Angel Island,” she said.

“At that very first pilgrimage, we were treated to a very dramatic play about a Japanese picture bride, written and directed by Judy Hamaguchi (SFJACL president), where Ryoji Oyama (another SFJACL board member at the time) played the lead as the farmer groom awaiting his bride,” Alice Kawahatsu continued.

Sleeping quarters of detainees (Photo: Emily Murase)

The play, titled “Longest Journey Home,” focused on the life of Toshiko Inaba, who, through a toxic combination of racism and sexism, became the longest-detained person of Japanese ancestry on Angel Island, despite having been born in Walnut Grove, Calif. After her 16-month detention which spanned from 1928-30, she was ultimately deported back to Japan. Later in life, she was able to rejoin family in the U.S., but this was many decades after the wrongful denial of her initial attempt to establish citizenship.

Judy Higuchi shares her family’s history at the pilgrimage event. (Photo: Mark Shigenaga)

At this year’s pilgrimage, the program focused on the impact of U.S. immigration policies on Asian American communities and personal family connections to the Immigration Station. Grant Din of the California Genealogical Society shared reflections on Nikkei connections to the island.

Judy Higuchi of San Jose, a descendant of a World War II incarceree, shared her story of how an inquiry by Marissa Shoji, a local Girl Scout pursuing her Gold Award, led to the discovery of new branches of her family tree, including family members who came through Angel Island.

Pictured (from left) are keynote speaker David Mineta with former Angel Island Gala Chair Nobuko Saito Cleary and Executive Director of the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation Edward Tepporn. (Photo: Mark Shigenaga)

David Mineta, son of the late longtime U.S. Congressmember and Secretary of Transportation Norman Mineta, welcomed the opportunity to speak about his grandmother, Kane Mineta, who arrived at Angel Island in 1914 as a 20-year-old picture bride.

“I am often asked to talk about dad, but today, I get to talk about grandma,” he quipped to the pilgrims. Through genealogical research conducted with Din, Mineta discovered many new details of his family’s immigration story, details he relishes sharing with the rest of his extended family.

Also finding a connection to his grandmother was former San Francisco Supervisor and retired professor of Asian American Studies at San Francisco State University Eric Mar, who recently discovered his Japanese ancestry through genetic testing. Since then, he has sought information about his grandmother, Kimiyo Mondo Kanemasu of Oakland, Calif. “I know she arrived on Angel Island as a picture bride from Hiroshima in 1913. On my next trip to Japan, I intend to visit Hiroshima,” Mar said.

Mar also noted the sexism he has encountered in doing genealogical research. “It is so much easier to find information about men since their names don’t change,” he said. “I’m trying to learn about each of my grandmothers, biological and nonbiological, Chinese and Japanese. It is definitely harder to find information about women relatives.”

To aid the pilgrims with their genealogical research, Linda Harms-Okazaki of the California Genealogical Society spoke about available resources. The event featured free family history consultations with a team of volunteers from the California Genealogical Society. Harms-Okazaki has supported the pilgrimage with free consultations over the years, publishes a regular genealogy column in the Nichi Bei News and conducts family history workshops in the Nikkei community. For her dedicated service, Taguma presented Harms-Okazaki with a Kansha Appreciation Award as part of this year’s program

Kansha Award recipient Linda Harms-Okazaki (center) with Kenji Taguma (left), Danielle Wetmore and Grant Din. (Photo: Mark Shigenaga)

Following the formal program, pilgrims were directed to the Angel Island Immigration Museum and the nearby Detention Barracks Museum. Rev. Kawahatsu conducted calligraphy name-writing, while others met with volunteer genealogists at the first museum. Pilgrims also browsed the barracks, furnished with period items, with a focus on the Chinese and Japanese poetry scrawled into the walls by sometimes desperate would-be immigrants over a century ago.

An intergenerational presentation of immigrant stories (Photo: Emily Murase)

On his first pilgrimage was Haruki Kato, a native of Gifu Prefecture. After spending a year at Cal State Stanislaus studying Japanese American history with Sheryl Okuye Sauter in 2023, he joined the staff of the Japantown Task Force in 2024 as part of his Optional Practical Training, which allows foreign national students and recent graduates to work legally in a related field of study. At age 24, Kato is about the age of many of the immigrants.

“The pilgrimage made me think about the many challenges endured by the early Japanese immigrants,” he said. “The bunk beds in the barracks were narrow and crowded together. How did early immigrants survive detention? I saw the poetry scrawled on the walls, mainly in Chinese, but some Japanese. It was sad and inspiring at the same time.”

Celebrated community photographer Mark Shigenaga, a Sansei from San Rafael, Calif., discovered his connection to Angel Island during the very first pilgrimage in 2014, which he described in a previous interview with ArtsEdForAll: “It was during this pilgrimage that I met Grant Din. A chance discussion subsequently led to an exploration of my grandfather, Kakuro, and great-uncle Shigeo’s history on this island, who were shipped from Hawaii to California and destined to become interned at various Department of Justice camps a few months after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Grant’s access to the National Archives and Records Administration led to a wealth of new insights to the journeys of the Shigenaga brothers and are, today, cherished by our family.” Shigenaga’s grandfather, Kakuro, and great-uncle, Shigeo, are both featured in the exhibit “Taken From Their Families,” which is located in the Mess Hall of the Barracks Museum.

The 2024 Nikkei Angel Island Pilgrimage provided community members the important opportunity to connect with their ancestors and each other, with ripple effects for months and years to come.

For more information about the Angel Island Immigration Station, visit https://www.aiisf.org/.

Author Emily Murase’s grandmother, Moto Murase, likely passed through Angel Island as a picture bride from Yamaguchi Prefecture to marry Mantsuchi Murase of Parlier, originally from the same prefecture.

Obon dancing at the pilgrimage (Photo: Mark Shigenaga)