Kokuho Rose Heirloom Rice (Photo: Gil Asakawa)

Koda Farms’ long history of rice is starting a new chapter.

By Gil Asakawa, P.C. Contributor

Robin Koda is eager to take visitors, including a reporter and a documentary film crew from the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo, through the history-filled land of Koda Farms, the iconic farm that was started 97 years ago by her grandfather, Keisaburo Koda.

Just about every Japanese American is familiar with Koda Farms — especially its best-known brands, Kokuho Rose rice and Blue Star Mochiko mochi rice flour. In Asian markets and even mainstream supermarket chains across the country, you’re likely to see stacks of Koda Farms’ rice (there’s also Sho Chiku Bai Sweet Rice) in bags from five to 50 pounds.

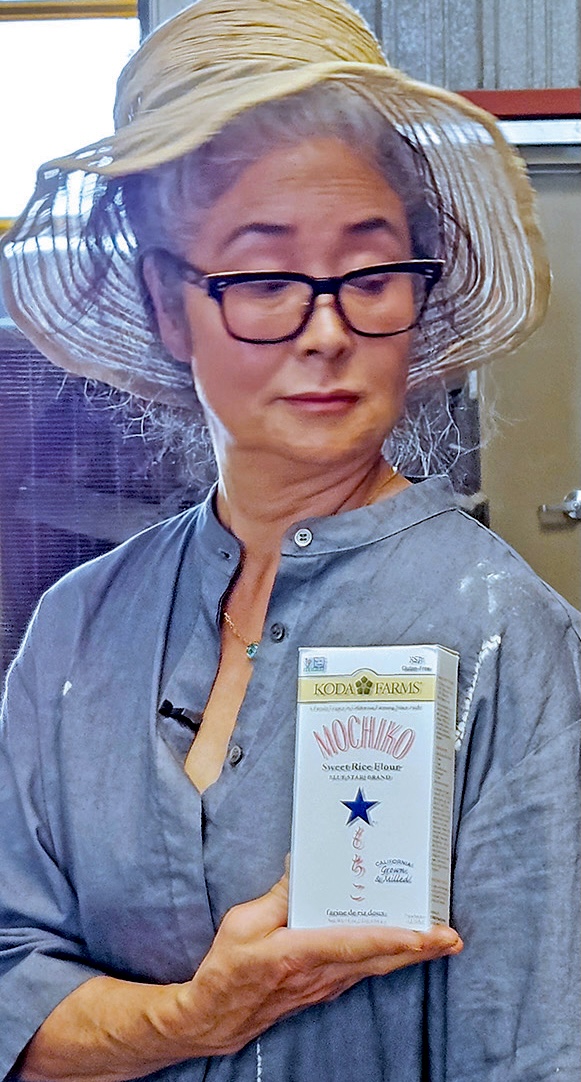

Blue Star Mochiko (Photo: Gil Asakawa)

Kokuho Rose, which was developed and first sold in the early 1960s, is credited in a story by the Los Angeles Times as being the rice that made the introduction of sushi in America possible, with its taste and texture the perfect complement to raw fish and nori seaweed. The rice helped convince restaurants in Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo to import the glass-refrigerated counter displays from Japan for the first American sushi bars.

(Read related story here.)

JAs know the rush to buy Kokuho Rose — especially the company’s “Heirloom” product — when the “New Crop” designation appears on the stack of sacks at the store each fall.

Robin Koda with Mochiko (Photo: Gil Asakawa)

But earlier this year, there was a panicked rush to stock up on Koda Farms products when news media, including the New York Times, ran stories about Koda Farms that gave the impression that the operation was shutting down. The actual story, if readers dug into the coverage, is that Robin and Ross Koda, the granddaughter and grandson of Keisaburo who now run the farm, have licensed five of the family’s products — including its seeds, processes, products such as Kokuho Rose and Blue Star Mochiko — to a Northern California company, Western Foods.

The New York Times, which broke the news to most of the country, proclaimed, “California’s Rice Royalty Is Stepping Down: Koda Farms, a family run rice business revered by chefs, ends a century-long tradition.”

Across the country, the San Francisco Chronicle’s even more dire headline read, “This California Farm Supplied Rice to Chefs and Homecooks for 97 years. Now, It’s Shutting Down.”

Both articles and others that followed mentioned the licensing deal and noted the products would continue, but readers, who might scan a headline but not fall for the click-baity sensationalism to actually read the details, just caught the gist of the story and assumed the worst.

Culinary fans thought that Kokuho Rose would not be available anymore, or that there would be no more Blue Star Mochiko sold to make butter mochi cake. But the products will still be available, and though it’s true the Kodas are giving up the tough life of farming in an age of economic strife and climate change, the farm will remain, and rice will still be grown there under the supervision of Western Foods, as well as at the company’s farms near Sacramento. There will actually be more rice from more land.

Robin Koda, who lives on the family farm in South Dos Palos in California’s Central Valley with her 99-year-old mother, Tama Koda, says the panic was immediate, and she was swamped with social media messages, phone calls and texts from fans far and wide.

Robin and Tama Koda (Photo: Gil Asakawa)

The Sacrarmento Bee had it right in its headline, which stated the Koda legacy is moving to Yolo County, where Western Foods is located north of Sacramento. The Los Angeles Times set the record straight with a headline and article that included this direct statement from Robin Koda: “Stop freaking out. Stay calm. This is Koda family legacy chapter two.”

The new chapter will be written by Western Foods. The company is licensing the right to use the Koda Farms name, as well as the names and logos for its famous products, in addition to Koda Farms’ special heirloom rice seeds and production processes.

The deal was made possible because Keisaburo Koda was visionary enough to trademark his products and brand names decades ago, so that they could someday be handed on as valuable assets.

Koda was a forward-thinker in many ways. Before WWII, Koda Farms was the largest rice grower in the U.S. Koda was called the “Rice King” by consumers and media. He invented an efficient way to sow rice seeds using airplanes to drop seeds that had been soaked overnight onto wet fields so they could withstand the Central Valley’s dry climate and soil. In the 1950s, he worked with a scientist to develop the special seed for medium-grain rice that would be sticky and chewy and have flavor and floral notes. It would eventually become Kokuho Rose.

But when Executive Order 9066 was signed, the Koda family — Keisaburo, his wife and two sons — was incarcerated at Amache in Colorado, where outside the family’s barrack was a concrete usu mortar to pound mochi.

After the war, though, the Rice King returned to California and found that almost all of his land and equipment had been sold. He simply moved down the road a couple of miles and started the farm where the Koda family has built a new rice kingdom over the decades.

Koda didn’t just farm the land (his sons took over), he began social justice and community efforts that included being a leader in the JACL, starting a program between the U.S. and Japanese governments to bring young Japanese farmers to Koda’s land to learn American agricultural techniques and even filing for and eventually winning (after his death, unfortunately) reparations for his wartime losses.

As a businessman, Keisaburo Koda made sure he wasn’t just growing rice to hand off to other companies to truck, process, mill and sell the end products. Koda made his operation vertically integrated, so his farm grew, harvested, dried, processed and cleaned, milled and packaged the products under his family brands.

“I’m extremely grateful and consider myself extremely lucky that he had the foresight to get his IP (intellectual property) all in order,” Robin Koda said as she gave a tour of the farm and all the industrial equipment and various buildings that take the rice from farm to end products.

Koda Farms (Photo: Gil Asakawa)

Her grandfather built a unique vertically integrated agribusiness that they could control every step of the way from growing to harvesting to processing and then selling products. “Right? I mean, that’s the only reason why we have these trademarks to continue to license out,” Robin Koda added.

And Miguel Reyna, the founder of Western Foods, is also glad for the founding Koda’s visionary acumen. Reyna knew about Koda Farms before he founded Western Foods in 2004, when he worked for a company that milled Koda’s rice. He says he was contacted by Ross Koda a year ago when Robin and Ross began to consider making the change. Western Foods is known for milling flours, including a host of gluten-free rice and ancient grain products, and he’s excited to become the company behind Kokuho Rose, Blue Star Mochiko and Sho Chiku Bai Sweet Rice and other products.

Reyna and Robin Koda say that consumers can expect new, modern products, including Mochiko pancake mix, mochi donuts and muffins, as well as future rice snacks, though hopefully not the hockey-pucklike rice snacks that have been a staple of supermarkets for years, but something more culturally appropriate. Reyna also runs a separate line of healthy snacks, Rivalz, so he knows snacks.

Western Foods will continue to manufacture such beloved Koda Farms products as Kokuho Rose, Sho Chiku Bai Sweet Rice, Blue Star Mochiko and other products. (Photo: Gil Asakawa)

Reyna agrees that some of the media coverage has been challenging. “Yeah, the stories were all overboard a little bit. I think the messaging sometimes didn’t come across very clear,” he said. He also acknowledges that consumers can be skeptical of change like this, especially when a family owned company’s products will be made by a different company. He says he respectes the Koda family’s achievement and hopes to maintain the Koda legacy with his own family. Two of his sons are in college, and Western Foods can become a multigenerational family legacy, too.

Some of the farming will continue at the current site, and he adds, “Really, the product is not going to change, and Ross and Robin are not going anywhere.”

Robin will continue, for now, to be the familiar face of Koda Farms’ rice (though she won’t be driving to farmers markets up and down California on the weeknds anymore). Ross will continue to work with Western Foods to run the seed program, though he’s also involved in a new business selling sake. Uka Sake is made from Koda Farms’ rice that is fermemted and shipped to brewers in Japan’s Tohoku region, where Keisaburo Koda emigrated from in the early 1900s, to be made into Uka Sake.

For Robin and Ross, who grew up on this land, played on the farm equipment and climbed the towers that rise up to give a view of the acres around the family compound all the way to the Coast Range mountains to the west, it was time to move on.

She’s convinced her grandfather would approve because he was a restless soul who left Japan for a life in the U.S. and tried his hand at several businesses before landing on rice farming.

The Koda legacy will continue, and the family will be forever connected to Kokuho Rose and the other rice brands, but it will continue under a new leadership, hopefully, as Reyna says, for another century.

Harvesting rice (Photo: Gil Asakawa)