Her book ‘Farewell to Manzanar’ shared story of

Japanese American incarceration with generations of young people.

By George Toshio Johnston, Senior Editor

Author Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston died at her Santa Cruz, Calif. home, the Pacific Citizen has confirmed. She was 90.

According to next of kin, the co-author of the acclaimed book “Farewell to Manzanar” died of natural causes on Dec. 21.

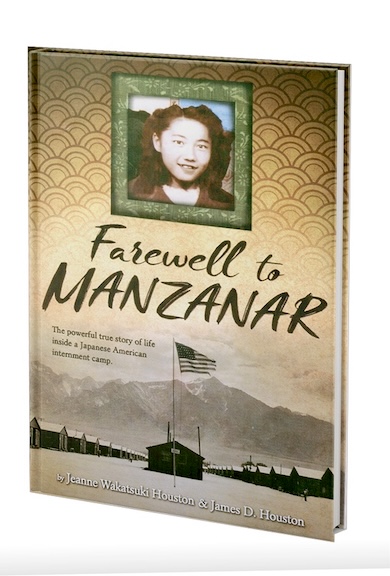

The book, published in 1973 and co-written by her husband, Air Force veteran James D. Houston, was Inglewood, Calif.-born Houston’s recollection from her childhood when, at age 7, her family and she were forced by the federal government to leave their Santa Monica, Calif., home, move to an assembly center and eventually become incarcerated at California’s Manzanar War Relocation Authority Center, one of 10 such remotely located concentration camps that during World War II detained ethnic Japanese, the majority of whom were U.S. citizens.

Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, with daughter Corinne Houston, displays the proclamation presented to her on May 12, 2018, by the city of Santa Monica. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Houston’s experience that was chronicled in “Farewell to Manzanar” — later adapted into a 1976 telefilm of the same name — paralleled what had happened to more than 125,000 Japanese Americans residing along the U.S. West Coast following Japan’s Dec. 7, 1941 attack on American naval facilities at Pearl Harbor in the then-territory of Hawaii — and President Roosevelt’s Feb. 19, 1942 issuance of Executive Order 9066, which authorized the Army to evacuate and relocate from the Western Exclusion Zone persons of Japanese ancestry.

“Farewell to Manzanar” was named by the San Francisco Chronicle as one of the 20th century’s 100 most important works of Western literature. As assigned reading in schools, generations of young people became familiarized — as told through the eyes of a child — with the experience of Japanese Americans who were incarcerated by their government for, according to the conclusions of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, “racism, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership.”

“Farewell to Manzanar” was named by the San Francisco Chronicle as one of the 20th century’s 100 most important works of Western literature. As assigned reading in schools, generations of young people became familiarized — as told through the eyes of a child — with the experience of Japanese Americans who were incarcerated by their government for, according to the conclusions of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, “racism, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership.”

“Farewell to Manzanar” would lead to Houston receiving many accolades in her lifetime. The Japanese American Citizens League recognized her in 2004 with a Japanese American of the Biennium Award for achievement in Arts, Literature and Communication. In 2019, she became a California Hall of Fame inductee. Among the other recognitions she received were the Japanese American National Museum’s Award of Excellence (2006); a Certificate of Commendation for Literature and History from the California Senate, Legislature and City of Los Angeles (2001); and the National Women’s Political Caucus’ Women of Achievement Award (1979).

The Houstons also co-wrote the screenplay for the telefilm adaptation of the book along with its director, Oscar and Emmy Award winner John Korty. (See Pacific Citizen, April 15, 2022, tinyurl.com/3as4jd94) The telefilm aired on NBC on March 11, 1976 and would be nominated for an Emmy Award. It won the 1977 Humanitas Prize in the 90-minute category.

In an email to Pacific Citizen, actor Clyde Kusatsu, who co-starred in the telefilm, wrote: “I was saddened to learn of Jeanne’s passing last month. … It was my honor to have been part of the realization of her book ‘Farewell to Manzanar’ into a film for NBC. She and John Korty came to East West Players to view a few of us in play we were doing at the time, and I was cast in the role of Teddy, her brother!

“During the shoot she came up to me to say how much I was able to capture her brother for the film. It was also an honor and privilege to contribute to the first film to tell the story of a Japanese American family and their part in the relocation experience, which was little known at the time we gathered to produce the film in 1975. It still stands as the only significant film on the subject. We were lucky to get it filmed.”

In 2018, accompanied by her daughter, Corinne, Houston returned to Santa Monica and spoke about her book at the auditorium of the main Santa Monica Public Library as part of its “Santa Monica Reads” program on the 45th anniversary of “FTM’s” publication, where she was presented with a proclamation by the city.

“I remember that trip to Santa Monica with my mom like it was yesterday,” Cori Houston wrote to the Pacific Citizen via email. “It was extraordinary to see her welcomed back by the current mayor and given a city proclamation to the community that she and her family had been taken from so many years ago.

“To me, it was an example of what my mom always believed was truly the strength of this country. That we live in a society where dissent and disagreement are allowed and when a light is shined on an injustice, there can be resolution. I hope we don’t lose that.”

In her Santa Monica address to the audience, Houston recalled how a simple question in 1971 from her college-age nephew who was curious about what he had heard about “the camps” from a professor left her stunned: “You were locked up in a prison. How do you feel about that?” (See Pacific Citizen, May 18, 2018.)

“He asked a question no one had ever asked before, a question I had never dared to ask myself,” Houston said. “How did I feel? For the first time in my life, I dropped the cover of humor and nonchalance and allowed myself to feel, and I began to cry. I couldn’t stop.”

As a result, her nephew’s question inspired Houston to write a family history, just for her large extended network of nieces and nephews, so they could know about where seven of them had been born.

“I was certain none of them knew about their birthplace,” she said. However, it proved to be a job she couldn’t complete. “I found that whenever I tried to write, I broke down and became hysterical and cried uncontrollably.”

Fortunately, Houston had an invaluable resource to turn to: her husband, James, who taught creative writing at Stanford and later, at the University of California, Santa Cruz. He would also become a distinguished visiting writer at the University of Hawaii and University of Oregon. He also received the Lurie Chair at San Jose State.

Despite Jeanne having been married for 14 years at that point and having known Jim for five years before that, he was as in the dark about his wife’s family’s history as their nephew.

“I had never told him about Manzanar,” she said.

Jim and Jeanne Houston (Photo: Courtesy of the Houston Family)

When she did tell him, he told her, “This is not a story just for your family. It’s a story everyone in America should know. Let’s work on this together.”

For journalist and author Frank Abe, who also appeared in the telefilm when he was an actor in the fictional role of Frank Nishi, there is continuing significance for all versions of “Farewell to Manzanar.” He told the Pacific Citizen, “It’s Jeanne’s story as a young girl …but I think the book and the film are remarkable in the sense that it does get the adult perspective.”

Art Hansen, California State University, Fullerton history and Asian American studies professor, serendipitously helped the telefilm capture that adult perspective. In an email to Pacific Citizen, he recalled how the book’s 1973 publication impacted his work, when his students and he were “immersed in studying and writing about various aspects of the World War II concentration camp experience at the Manzanar War Relocation Center in the Owens Valley of California. As a consequence, Jeanne Wakatsuki and James D. Houston’s book became a veritable bible for us.

“This was certainly the case for me and one of my graduate students, David Hacker, who together authored a 1974 article in the Amerasia Journal entitled ‘The Manzanar Riot: An Ethnic Perspective.’ While I never had the honor of meeting Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, in fall 1979 at a planning session held on the campus of California State University, Bakersfield, for a California Council for the Humanities project on the Dust Bowl migration of the 1930s called ‘California Odyssey,’ I was approached by James Houston, who kindly related to me how helpful Hacker and my article had been in providing an enlarged historical context for the production of John Korty’s 1976 nationally televised NBC movie ‘Farewell to Manzanar.’ ”

In other words, it was a case where a book inspired academics, who in turn informed the teleplay based on the book’s recollections of the co-author who, as Abe put it, was, “too young” to have been able to bear witness to “the subsequent teleplay’s Manzanar riot sequence.”

The riot sequence, was, Abe told the Pacific Citizen, a “fairly accurate representation of the Manzanar revolt and it presented lightly fictionalized versions of Harry Ueno, Joe Kurihara and Fred Tayama and Ralph Merritt to the American viewing audience. That that was quite an accomplishment, even now.” In the telefilm, Abe’s Frank Nishi character was inspired by JACL member Tayama, who was assaulted by Ueno of the Kitchen Workers Union. The beating, according to the Densho Encyclopedia, “ … set off a chain of events leading to a riot/uprising at the camp.” Kurihara was a Hawaii-born World War I veteran and Manzanar incarceree; the fictionalized version of him — Joe Takahashi — was played in the “FTM” telefilm by actor Seth Sakai. Merritt was Manzanar’s director.

Jim Houston predeceased his wife and family on April 16, 2009 at 75. The couple are survived by their three adult offspring, Corinne, Joshua and Gabrielle.

“Farewell to Manzanar” the book and movie are available for purchase from the Japanese American National Museum’s gift shop. The paperback is available for $10.99 at tinyurl.com/5n6jyw7m. The DVD, now with Japanese language subtitles, is available for $24.95 at tinyurl.com/yx87v6sb.

Home movies of Manzanar from the family of Ralph Merrit that includes footage of Manzanar high school’s 1945 graduating class and other Manzanar footage may be viewed at youtube.com/watch?v=vToNvZ6Vq2Y.

To listen to a 2020 interview with Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston conducted by Guy Kawasaki for his “Remarkable People” podcast, visit guykawasaki.com/jeanne-wakatsuki-houston/.