Interior shot of the department store in Callao, Peru, owned by the grandparents of Art Shibayama, circa 1931. Foreground is Kinzo Ishibashi, with Misae Ishibashi in the background, holding Art Shibayama as an infant.

Forced by the government to flee his home in Latin America as a result of World War II, Art Shibayama fights to legally restore the wrong he and hundreds of others suffered decades ago.

By Diana Morita Cole, Contributor

A boy, asleep at the beach, is shaken by his grandmother. “Oye! Abre tus ojos, Arturo! Vamanos.” A few feet from his sprawled legs, waves embrace the shore while ghost crabs scurry to the high ground to avoid the surge. He awakens and sees the purple rays of the setting sun splayed across the water. The boy reaches for his grandmother’s hand and walks to the awaiting black sedan, a uniformed chauffeur at the wheel.

When he was born in 1930, Art Shibayama began life under idyllic circumstances. His father, who had emigrated from Japan 10 years earlier, had become an entrepreneur of note in Lima, Peru, turning his profits from operating a coffee shop into a prosperous shirt-manufacturing business.

Young Art spent his summers with his maternal grandparents, who owned a thriving department store, and they often accompanied their grandson to the beach. And when he was old enough to attend school, Art and his younger sisters were driven to a private school by a chauffeur.

Insulated by such luxury, Shibayama was unaware of the hostile economic and racial currents that buffeted his prosperous ethnic community. Riots against the Japanese in 1940 resulted in the deaths of 10 Japanese Peruvians, and after the bombings of Pearl Harbor, racial hatred increased.

The Peruvian government decided to make use of a FBI blacklist of enemy aliens comprised mainly of the names of community leaders, including Art’s father, Yuzo Shibayama. Using this blacklist, which was unsubstantiated by evidence, the Peruvian government identified these men as threats to the state and began rounding them up.

So, in 1941, Yuzo became a wanted man. He would intermittently flee his home and hide in a small town in the Andes to escape the notice of the authorities. He left for the mountains whenever he heard an American ship had docked at the Port of Callao, the chief seaport in Peru, since he knew the ships were being used to abduct his friends.

The Etolin was the first American ship to sail away from the port of Callao with illegal human cargo. Onboard were Germans, Italians and Japanese “enemy aliens,” the jetsam discarded by South America. As it sailed northward, the Etolin made two more stops: one in Ecuador to pick up Germans and Japanese and one in Colombia to pick up Germans and Italians.

Yuzo, though, managed to avoid capture until the authorities decided to arrest Tatsue, his wife, and use her as bait to draw him out of hiding. Art’s sister, Fusa, refusing to leave her mother’s side, was jailed along with Tatsue until Yuzo turned himself in to the police.

In 1944, Yuzo, Tatsue and their six children were herded aboard the Cuba by U.S. soldiers armed with machine guns, rifles and whips. Their properties, passports and legal documents were seized as they embarked on a 21-day journey that would change their lives forever.

Aboard the Cuba, Yuzo was not allowed to see his wife nor his young daughters and sons because he and his eldest son, Art, were confined to the lower deck with the other adult males.

Art, now a captive, felt fear as he searched the vast horizon, devoid of familiar landmarks. Turning his back to the ocean, he looked toward the hold where he and his father were confined. Beyond the armed soldiers that scrutinized his every move, he saw that his ship was part of a convoy of four U.S. destroyers and two submarines.

After stopping briefly for supplies in Cuba, the Latin American captives reached New Orleans and were then arrested by the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service. Marched to a warehouse, the men, women and children were ordered to strip and doused with DDT. Art’s sister, Fusa, later told him she’d never felt so humiliated, having to strip in front of strangers.

Art, now 13 years old, and his family were whisked by shuttered train to Crystal City, Texas, and confined for two and a half years in a Department of Justice Camp, euphemistically called a “Family Internment Camp.”

The internment site also held Italian and German prisoners of war in facilities separate from the Latin Americans. Resident aliens of German and Italian ancestry as well as their children, who were American citizens, were also imprisoned there, along with Japanese Americans expelled from the West Coast and Hawaii.

In total, more than 2,200 Japanese Latin Americans (nearly 1,800 from Peru) were kidnapped from their countries of residence and birth and smuggled into the U.S. in exchange for trade agreements, military aid and loans. Among these hostages were Art’s maternal grandparents, Kinzo and Misae Ishibashi.

Even before he left Peru, Art knew from letters they’d sent to his parents that his amama and apapa were being held captive in Seagoville, Texas. Kinzo and Misae Ishibashi were detained in Texas and used in an exchange for American citizens living in Japan and in Japanese territories.

“After my grandfather and grandmother were sent away to Japan, I never saw them again,” said Art Shibayama.

It may have been, as writer Greg Robinson suggests in “A Tragedy of Democracy,” that this program of extraordinary rendition began when America was losing the war in the Pacific and was desperate for prisoners to use in exchange for American citizens stranded in Axis countries, since Japanese soldiers routinely evaded capture by committing suicide.

In 1946, a year after the end of the war, Art’s family was released from captivity. No longer of any value to its foreign policy stratagems, America pressured the government of Peru to take its former residents and citizens back. But of the 1,800 taken captive, only 80 Japanese Peruvians were permitted to return. America then ordered the remaining Japanese Latin Americans to be deported to Japan — a country devastated by war and one many had never seen.

Rather than submit to deportation, Yuzo decided to remain in the U.S. Fortunately through the humanitarian work of a civil rights lawyer, Wayne Collins, a parole program was initiated, allowing the Japanese Latin Americans to stay in the U.S. as long as they were able to secure a sponsor. And that sponsor, for many of the Japanese Peruvians, turned out to be an opportunistic corporation in New Jersey called Seabrook Farms, which was in need of cheap labor after the war.

Seabrook Farms hired children as well as adults. The adults worked 12-hour shifts and were paid an hourly rate of 50 cents for men and 35 cents for women. To help feed their family, Art and Fusa, now both teenagers, worked in the flower nursery. When Art turned 17, he was transferred to the plant where he worked seven days a week during the peak seasons. For three years they labored, deprived of the opportunity to return to school.

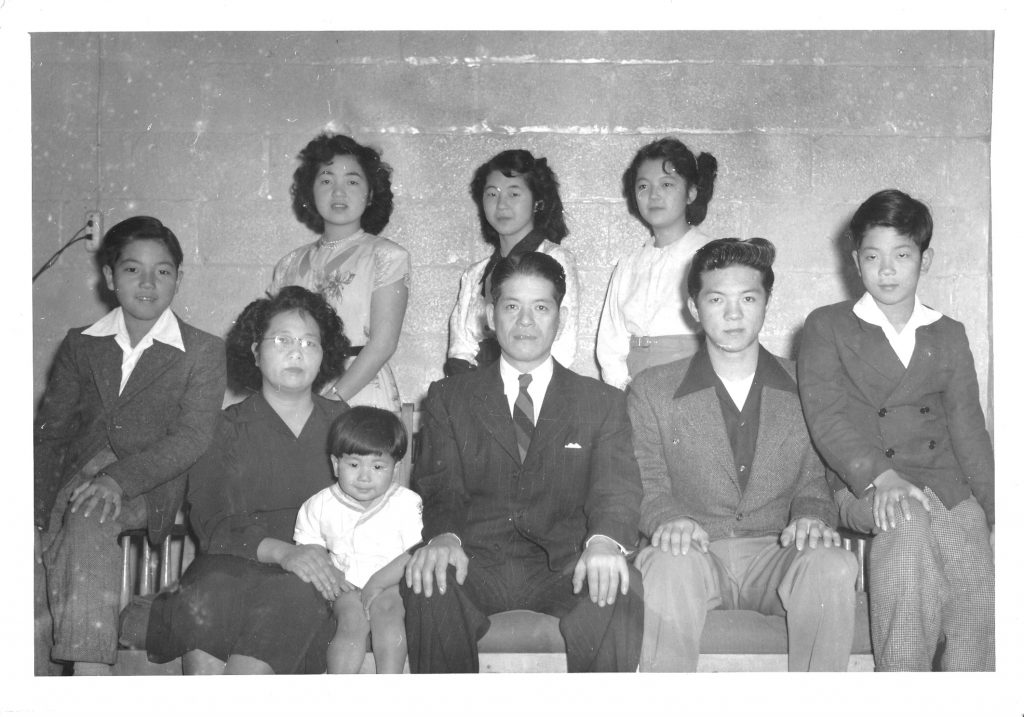

The Shibayama family in Chicago, circa 1950. Standing, from left, are Fusa, Susie and Rosie Shibayama. Seated, from left, are Tak, Tatsue, George, Yuzo, Art and Kenbo Shibayama. (photo courtesy of Betty Shibayama)

The Shibayamas, along with all the other workers at Seabrook Farms, lived in barracks and were forced to buy their provisions from the company store, which charged high prices. The former hostages from Latin America were completely responsible for their own economic survival, which was made even more difficult because their meager wages were taxed at 30 percent, the rate for illegal aliens.

In 1949. while still fighting deportation orders, Yuzo, along with other Japanese Peruvians, decided to move to Chicago. There, he tried to rebuild his life. He was able to access his funds in Peru and bought a substantial apartment building in the Uptown area of the city.

His family worked hard to integrate themselves into the existing Japanese American community. The majority of Nikkei in Chicago were also refugees, people who had been forced out of their homes and imprisoned in the United States.

Art found work at the American Carbon Paper Company and enjoyed the social activities for young adults organized by the Midwest Buddhist Church. There, he met Betty Chieko Morita, who would later become his wife, at the Bowlium, an Uptown bowling alley.

“The girls were crazy about him when he first came to Chicago!” recalled Betty Shibayama. But Fusa didn’t enjoy the same reception. She said she felt marginalized by the Japanese Americans due to her Peruvian accent.

Art Shibayama after being drafted into the Army in 1952. (photo courtesy of Betty Shibayama)

In 1952, still classified as an illegal alien, Art was drafted into the U.S. military and sent off to Europe. The young boy, kidnapped from Peru by America and denied legal status, was now expected to defend the country that had hijacked his family, imprisoned him and condemned him to a life as a stateless person.

While stationed in Germany, his superior officer convinced Art to apply for American citizenship, but the U.S. government deemed him ineligible because he had entered the U.S. illegally, without a visa.

Upon his return to Chicago, Art learned that two members of his family had been permitted to apply for U.S. citizenship during his absence. Deprived of the opportunity to obtain citizenship like the others, he traveled to Windsor, Ontario, in order to gain legal status through re-entry into the U.S. from Canada.

Art finally achieved legal alien status in 1956. “It’s not like we wanted to come here,” Art said. “We were forced to come here. What the U.S. government did was unjust!” Finally in 1972, after 28 years, Art was finally allowed to become an American citizen.

Two decades later, former Japanese Latin American internees and their families revived their struggle for redress with the founding of “Campaign for Justice: Redress NOW for Japanese Latin Americans!” because they had been excluded from the settlement under the Civil Liberties Act of 1988.

And in 1999, the Mochizuki v. United States 43 Fed. Cl. 97 lawsuit resulted in a controversial settlement offered to former Japanese Latin American internees still living in 1988.

Art, however, decided to opt out of the settlement. “It was like a slap in the face,” he said. He felt the offer was hasty, demeaning and disingenuous — without regard for the scope and severity of the injuries sustained by him and his family.

In 2000, Art, along with his two brothers, launched the Shibayama, et al. v. U.S. lawsuit for their discriminatory exclusion from redress under the Civil Rights Act of 1988. This lawsuit was dismissed on procedural grounds in federal claims court.

With the failure of four more lawsuits and the failure of two pieces of legislation, Art and his brothers filed Petition 434-03, Shibayama, et al. v. United States with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, a body of the Organization of American States, stating that crimes had occurred under the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man, an international human rights accord.

Campaign for Justice, Washington, D.C., 1997. (photo courtesy of Betty Shibayama)

Next month, 14 years following the submission of their petition, representatives of the Commission will decide at a public hearing whether Art and his brothers will be allowed to present their case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

According to Grace Shimizu, coordinator of the Campaign for Justice: “This will be a historic event, the very first time that Art’s case will be heard and assessed on its merits. Up until now, the U.S. government has been putting up technical roadblocks and asserting that the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has no jurisdiction because the OAS was not in existence when the violations occurred. But we know that there is no statute of limitations on war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Shimizu continued: “Until such crimes have been properly redressed, they are considered to be ongoing crimes. The U.S. government cannot be allowed to act with impunity and evade accountability. Art’s case is so significant and relevant, not only for the Japanese Latin American internees, but also for all people in the U.S. and around the world. This case goes straight to government accountability for wrongdoing, the rule of law, defending the Constitution and applying human rights law and treaties in the United States.”