Vietnam War-era veterans Mike Nakayama, Art Ishii and David Miyoshi, superimposed over the Three Soldiers statue. (Photo: Marie Samonte and George Toshio Johnston)

Scars, questions still haunt Nikkei who served during America’s most-controversial war.

By George Toshio Johnston, Senior Editor, Digital & Social Media

More than four decades have passed since the Fall of Saigon ended the United States’ military exploits in Vietnam and other parts of Southeast Asia. The Vietnam War was the first war America lost.

That war, plus the ever-present Cold War, combined with changing social norms and challenges to the status quo that arose in the 1960s — the Civil Rights Movement, the Anti-War Movement, the Draft, the Generation Gap, Women’s Liberation, assassinations of national leaders, increased environmental awareness, psychedelic drugs and that so-called music young people were listening to — strained nearly every facet of American life to the breaking point.

The Japanese American community was not unaffected by those strains and changes that were blowing in the wind. When the term model minority was coined in 1966 by the New York Times in reference to Japanese Americans, there were, below that composed surface, fissures that would manifest soon in campus unrest, drug abuse, gang activity, a burgeoning Yellow Power Movement — and mixed feelings by Asian Americans about being called upon to go to war against other Asians to keep communism at bay in a land that many might have been challenged to find on a world map.

In the larger society, those strains would impact even the political fortunes of the men who sat in the Oval Office. Now, with a new, polarizing POTUS occupying that same Oval Office, it’s worth noting that many splits and strains seem to be on the rise again, meaning it may be the time to revisit the still-ringing reverberations caused by the Vietnam War.

“People, welcome to Vietnam,” bellowed the senior NCO of the Tropic Lightning Division Replacement Training School. “You have arrived at the end of the world. Gravity does not exist here. You remain on the ground only because this whole country sucks. Even the birds here fly upside down because there’s nothing worth shitting on in the whole country.”

— Excerpted from “Wolfhound Samurai,” written by Vincent H. Okamoto

When the 10-part, 18-hour long “The Vietnam War” premiered in September, the first installment of the Ken Burns-Lynn Novick-directed epic documentary garnered the season’s highest Nielsen ratings for pubcaster PBS.

Among the dozens of soldiers and civilians interviewed for the documentary was Vincent H. Okamoto, a former Army Ranger who served in the infantry as a second lieutenant in Vietnam circa 1968. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and would eventually be inducted into the Army Ranger Hall of Fame.

A Los Angeles County Superior Court judge since 2002, Okamoto also authored “Wolfhound Samurai,” a novel inspired by the experiences his men and he encountered while fighting in the jungles, swamps, tunnels and rice paddies of Vietnam.

While Okamoto’s profile was raised thanks to “The Vietnam War” documentary, there were other Japanese Americans who served in the U.S. Armed Forces during that war.

On a recent evening in Long Beach, Calif., the Pacific Citizen hosted an informal dinner at Number Nine — not ironically, a Vietnamese restaurant owned by Hideki “Dickie” Obayashi — to discuss with three Japanese American Vietnam War-era vets their experiences from decades ago, compare notes and talk story about their not-so disparate experiences.

At 73, Art Ishii is the eldest amongst the trio of vets and the lone member of the Air Force, the military branch in which he served during the 1960s for five years — two years stationed at Sheppard Air Force Base in Texas, which he hated, and then three years stationed at Tachikawa Air Base in Japan, which he loved.

“I was so happy to get the orders to go to Tachikawa. Frankly, for the most part, the three years when I was overseas were some of the best years of my life,” said Ishii.

But before that assignment, Ishii says he recalls two huge events that happened in his first year of active duty.

“I got out of boot camp and immediately there was the prospect of World War III because of the Cuban Missile Crisis,” he said. “We’re on alert for like, 60, 90 days, because we were a Strategic Air Command base. Within a year, (President John F.) Kennedy gets assassinated. Boom. We go on red alert again, and I’m guarding a B-52.”

At the time for Ishii, Vietnam was the furthest thing from his mind. Although never stationed in Vietnam, he did visit while on TDY (temporary duty) during his stint at Tachikawa, which he saw go from a small, sleepy American military outpost to a buzzing pit stop for the thousands and thousands of U.S. troops on their way to Southeast Asia as America’s involvement in the war escalated.

“… 2.7 million Americans would be sent to fight in Vietnam. More than 58,000 would be killed. Nearly 300,000 would be wounded. Over 2 million Vietnamese would die.”

— “Wolfhound Samurai”

“You started hearing little ripples about places you’ve never heard of before — French Indochina, then you start hearing about Vietnam. By the time they joined, Vietnam was obvious,” Ishii said.

The “they” to whom Ishii was referring are David Miyoshi and Mike Nakayama, both 68, who each served in Vietnam as Marines, officer and enlisted, respectively — and both had experiences while in training of being singled out as Americans of Asian ancestry, including being called racial slurs that are no longer tolerated in today’s military.

While Nakayama recalls being “so traumatized” by the entire boot camp experience that when it happened, “it was just another incident” — but the time when a drill instructor called him up before at least 100 other recruits during a lecture remains an unsettling memory.

“This drill instructor looks at me and goes, ‘Pvt. Nakayama, stand up.’ I was like, ‘Oh no, what did I do now?’

“I stood up, and he goes, ‘Turn around so everybody can see you,’” Nakayama continued. “So, I did a 360, and he goes, ‘All right everybody, this is what a gook looks like. You remember this because this is the person that you need to kill when you get over there. You can sit down now.’”

Nakayama remembers being worried, thinking, “This is not cool because everyone’s going to have loaded weapons and if I look like [the enemy], what’s going to keep them from doing something to me?” Fortunately, Nakayama said that when he got to Vietnam, he wasn’t “singled out as an enemy by my fellow Marines.”

For Miyoshi, when he was in the 13-weeklong Officers Candidate School, an older, wizened NCO who had fought the Japanese at the Battle of Guadalcanal during WWII seemed to zero in on him.

“Sgt. Keyes was always just staring at me,” Miyoshi said.

Noting that there was a 30 percent failure rate for OCS, the challenges were not just physical — which Miyoshi says were quite severe — but also mental, emotional and psychological.

“They’re constantly messing with your head,” Miyoshi said. “That racial element — not only for Asians, but also for blacks and Latinos — this is the weakest point, they believe, for a human being, that sense of who you are and if they can attack that part and they can get this guy off balance, they can see what you’re made of.”

Miyoshi remembers, ironically enough, that on Dec. 7, 1966 — two weeks away from learning if he would graduate or not — Sgt. Keyes yelled, “Sgt. Miyoshi, get your fucking ass up here,” summoning him in front of the other candidates.

The sergeant tossed him a rifle and had him put on a coolie hat and black clothing.

“All right, face us now and growl, goddamn it,” Keyes ordered him. To the assembled candidates, Keyes said, “This is what you’ll be facing in ’Nam, and when you see it, you kill it! You got that? You kill it!”

“I was getting kind of angry,” Miyoshi recalled, while thinking, “Why blow it now? Just look down.” Keyes then ordered him to put the props away.

“As I was putting the stuff back, an arm comes around me,” Miyoshi said. It was Sgt. Keyes. In a whisper, he said, “Candidate Miyoshi, you’re going to make a fine lieutenant.” Then he just turned around and walked away. It was sort of an early Christmas present for Miyoshi, being told two weeks before everyone else that he had passed OCS — and his next two weeks were stress-free.

Unlike Nakayama and Miyoshi, Ishii didn’t himself have a similar story of being singled out during boot camp for being Asian.

“When they were coming in, I was already on my way out,” he said, noting that their experiences and perceptions were much different from his, due to where the U.S. involvement in Vietnam was at the time.

“It’s not just the Viet Cong and the NVA you have to fear. Nearly everything in this treacherous country can kill you. An innocent looking object you pick up might be a booby trap rigged to explode in your face. Drink water without purification tablets, and you’ll get dysentery. Stay out in the sun without headgear, and you can die of sunstroke. If you don’t take malaria pills, you can die from a mosquito bite. You can get blood poisoning from infected leech bites. Vietnam has some of the most poisonous snakes on earth: cobras, kraits and pit vipers. If a krait bites you, the medics can’t help. You’ll be dead in 30 seconds, so just bend over and kiss your ass goodbye.”

— “Wolfhound Samurai”

When he was stationed in Vietnam, Miyoshi was part of a combined action platoon — and his first day, while amusing in retrospect, was not so funny at the time, as it underscored the potential hazards of being an American with an Asian face.

As it began to get dark, Miyoshi decided to use the officer’s shower. After removing his uniform and while showering, a loud siren went off.

“I was thinking, ‘This probably isn’t good,’” he said. He was correct — the camp was getting hit with a rocket attack. “All of a sudden, boom, boom, boom!”

Just then, a Marine sergeant was walking by.

“He sees me — an Asian, cowering in the officer’s shower, and he runs in there, and he grabs me and throws me against the wall,” said Miyoshi.

The sergeant continued to curse at Miyoshi and physically assault him.

“My clothes were in the far corner. I didn’t have anything on. I didn’t know what to do, so I did the only thing I could think of. I shouted out in English, ‘Goddamn it, sergeant, if you touch me on more time, I am going to have you court martialed.’”

The African-American sergeant backed off, uncertainly, and the next morning, an embarrassed Sgt. Bell showed up in front of Miyoshi’s desk at 0800 and said, “Lt. Miyoshi, I’m sorry about last night.”

Apology accepted, and Miyoshi said from that point on, they had a great relationship. “He was one of my closest sergeants that I had.”

Less amusing was what happened to Nakayama when he and his men were hit by a rocket.

“I was medevac’d to Da Nang,” he said. Nakayama had shrapnel in his head and face, blown-out eardrums and he had been shot in the chest. Nakayama still has shrapnel in his shoulder.

“They took me to the triage,” he recalled. “I was on a stretcher, and they laid me down next to about eight other guys from my squad and my platoon. One by one, they took each of them away and treated them. I was just lying there. I said, ‘Hey man, you forget about me? Are you going to do something for me?’ They said, ‘Shit, why didn’t you tell us you was a Marine? We thought you was a gook!’ I was like, ‘Good thing I said something because they were going to let me fucking bleed out.’”

In addition to being awarded the Purple Heart, Nakayama also received a Bronze Star for, as he put it, rescuing a couple fellow Marines.

“There was no grand cause or noble crusade to fight and die for in Vietnam. Inevitably, idealism turned to skepticism then deteriorated into cynicism.”

— “Wolfhound Samurai”

If World War II was “the good war,” and the Americans who fought in it were “the greatest generation,” then the Nisei men who served in the Army’s segregated and acclaimed 100th Battalion/442nd Regimental Combat Team had to be considered among the best of the best — and that legacy was something that loomed large over the next generation of Japanese Americans that came of age in time to serve during the Vietnam War.

“As a Japanese American kid, I heard the stories about the 442nd and how much they were touted as heroes of our community and our nationality. They were glorified,” Nakayama said. “It had a kind of influence in that sense of being part of that.”

Ishii concurred. “I’ve got uncles who were 442, MIS. You hear of their legendary heroism, things like that,” he said.

Compared to WWII, however, the Vietnam War took place not only at a different time, but it also was under a completely different context.

“WWII had a justification and a meaning,” according to Miyoshi, and that was Pearl Harbor.

“We didn’t have that in Vietnam,” he said. “All we had were platitudes. ‘We have to stop the scourge of communism, the Domino Theory. If Vietnam falls, then come Cambodia and Laos.’”

As for the war itself, Miyoshi said, “The United States screwed up because we fought the wrong war.”

He says there were two wars going on — the smaller war in which units like his combined action platoon — a squad of Marines and a platoon of South Vietnamese regulars — would live in a village together. It included using propaganda and collecting intelligence, but also trying to teach villagers skills like animal husbandry, constructing buildings and raising crops.

“Then there was the big or conventional war led by [Gen. William] Westmoreland. That, to me, was the biggest failure because the whole strategy of the big war was search-and-destroy, search-and-destroy,” said Miyoshi. “All you’re doing is messing up the country and getting everybody pissed off.”

Arguments as to whether the U.S. should have been there in the first place aside, he felt a nationwide “capture-and-hold” approach would have been a better strategy.

Nakayama was blunter in his assessment.

“The Domino Theory was bullshit,” he said. “It still is.”

Compared with WWII, Nakayama says there was a greater sense of purpose for Japanese Americans who fought for the U.S.

“It was almost a matter of proving how American Japanese were. It was an opportunity that the 442nd partially took on as a reason,” Nakayama said.

In contrast, he says the Vietnam War was America attacking a sovereign nation and not a case of “defending ourselves.”

Despite this, Nakayama said he had no hesitation when he volunteered to join the Marines and fight in Vietnam after graduating from Dorsey High School in L.A.’s Crenshaw area — and he ignored those who had been “in country” and counseled him against enlisting.

“I had three friends who had been in [Vietnam] and had come back — actually, only two came back. One of them was killed in Khe Sanh … they never found his body,” Nakayama said. “He got hit with a mortar at his feet, and he was gone.

“I knew these guys and they were telling me, ‘Don’t go. Don’t do this,’” Nakayama continued. “And that just made me want to do it more. It was like challenging me, which was a mistake. It’s not easy for me to rationally explain. It was just that things were so bad in my day-to-day life with my friends. We were just in this downward spiral of fighting and taking drugs.”

It got to the point where Nakayama thought he was going to either die on the streets or get out of there and change his life. Volunteering for Vietnam, however, turned out to be a leap out of the frying pan and into the firefight.

Ishii, who said he also joined the service to escape an environment that had him on a path toward a life of crime and violence, was one of those older guys who advised younger guys about what was going on in Vietnam.

“I was home on leave, maybe ’66 or ’67, and one guy, maybe a year, year and a half younger than me, came running up to me. He said, ‘Hey Art, I want to talk to you. I just got drafted.’

“I remember telling him, ‘Have you considered going to Canada or joining the Coast Guard or the Reserves or something like that?’” he continued. “‘If you go in, you’re going to boot camp, and you’re going “in country.” That’s all there is to it.’ We talked for a while about what his options were, and I just remember we went on to other things.

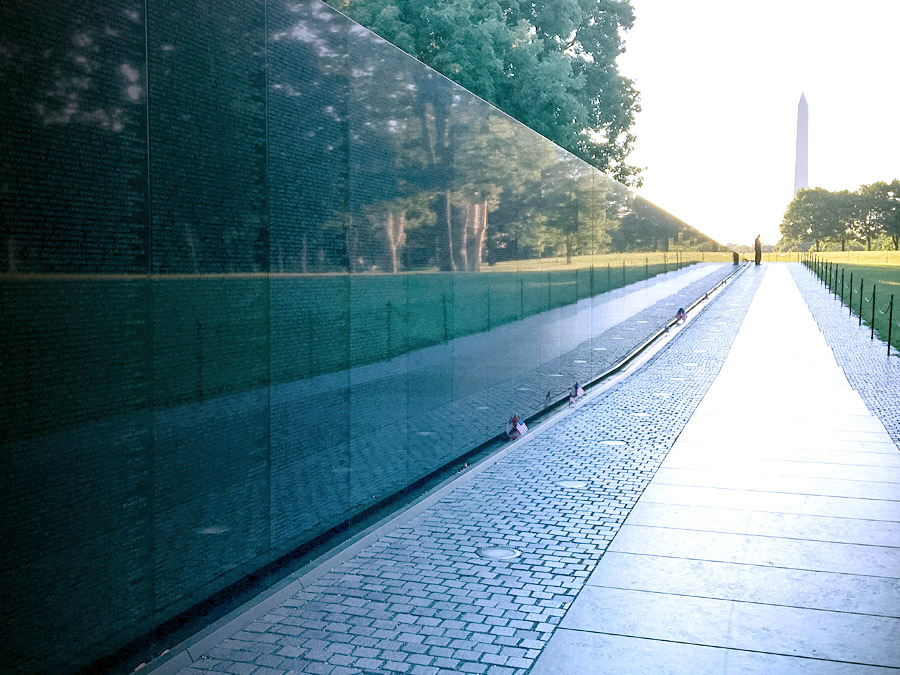

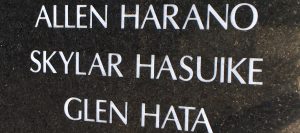

“I got back overseas and just a few months later, I got a letter that he had gone to Vietnam and within three weeks, he was killed. I always wondered, ‘Did I impress upon him deeply enough?’ His name’s right there on the [Memorial Court] wall. I go visit him every time I go into Little Tokyo,” Ishii concluded.

Skylar Hasuike’s name is among the many on the wall of the Japanese American Veteran’s Monument in Little Tokyo, which contains the names of veterans of Japanese ancestry who were killed while serving in the U.S. military.

His name was Skylar Hasuike.

“For many returning veterans, it was a bittersweet homecoming marked by cold indifference or overt hostility.”

— “Wolfhound Samurai”

Because of their service, Ishii, Miyoshi and Nakayama all had experiences most civilians avoid. Despite not having a combat role, Ishii was surprised by a medical diagnosis related to his five years in the Air Force.

“It was 40 plus years later that the VA told me — and I was absolutely shocked — that I had PTSD (posttraumatic stress disorder),” Ishii said. “I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. Mike would have PTSD. David would have PTSD. I got no business having PTSD! But over the course of the VA getting to know me, they said it was classic, yours is just emerging now.”

As the Vietnam War escalated and the workload at Tachikawa’s big hospital facilities grew, Ishii says he volunteered to help.

“I thought I was a tough guy, but I walked down the hospital ward where I was supposed to look after these guys,” Ishii said. “I walked about six beds deep, and I turned around and walked out, and I leaned up against the wall. My knees were weak.”

What he saw were fellow Americans, about the same age, with half their faces blown off, missing limbs and with holes in their bodies big enough to see through.

“And maybe the next day you meet and greet some young kid on his way to Vietnam, and he can’t wait to kill a gook for God and Country,” Ishii said.

Nakayama recalls how he and his men would be used to draw enemy fire and then take cover.

“The lieutenant would call in airstrikes and artillery and blow up the immediate village that we thought it came from,” he said. “We would go through that village and find nothing but small children and old women and old men, and they were all blown into pieces. I mean, pieces of a baby’s head. I could see the inside of a skull that looked like cheese on a pizza.”

With body counts serving as the measurement for success in the prosecution of the war, if they found 20 body parts, they’d count it as 20 bodies.

“That’s one of the main things I still think about. I have recurring dreams about that shit because I can’t get it out of my head,” Nakayama said.

“Like Mike was saying, there are some scenes that are so difficult to erase. Body parts, yeah,” Miyoshi concurred. “I had to, 14 years after coming back, go through therapy for PTSD. I was waking up with nightmares. I was taking medication and all that. Gradually, time heals. Knock on wood, but I don’t have any of those dreams anymore.”

Because of his war wounds, Nakayama says he came back to “the World” — GI slang for the U.S. — on a stretcher, eventually being sent to Long Beach Naval Hospital. Once discharged, readjusting to civilian life was a new challenge.

“I felt like I had just come back from Mars,” he said, laughing at it now. “When I came back, I didn’t want to ride in a car. I felt so fucking vulnerable. I had to sit in the back, and I was like, ‘Slow down, goddamn it! I’m going to fucking die here after surviving the fucking war!’”

In addition to PTSD, all three vets said they still feel residual anger.

“There is anger. There is anger of our country, because of politics, put young men through all of this,” Miyoshi said.

For Nakayama, there are also actual physical reminders. “Having shrapnel in my body affects me everyday,” he said. “There’s not a day that I don’t think about it. My ears are ringing louder than any sound that you might hear on a day-to-day basis.”

If there’s any lesson to pass on from his experiences fighting in Vietnam, Nakayama said, “The best thing I can do is let people know that it was a bad war.”

The wisdom Ishii says he got out of his military service in the 1960s during the time of the Vietnam War is more general.

“We have to just remain vigilant. We, as people of color and as Asian Americans, need to look out for ourselves. How do you do that? You have to be proactive, you have to be vigilant and know our history,” he said. “I don’t have any kind of link or tie to China or North Korea. But to the general population of, say, whites, we’re one and the same. That’s why we were gooks. It didn’t matter that we were Japanese. Like Mike says, we need to stay out of other people’s business unless they really come knocking on our door and bombing our shores.”

As for Miyoshi, serving in the military and being stationed in Vietnam gave him a newfound gratefulness for being an American in America.

“I really got to appreciate America for what it had when I came back,” he said. “I gained an appreciation for what we have here, albeit we have some pretty messed up politicians and things like that here. That is one of the sole benefits of going through Vietnam — appreciating America.”