The Kingi family, from left: Elaine, Robert, Kim, Ronnie, Ricky and Rick. (Photo: Athena Mari Asklipiadis)

Kingi’s Kajukenbo: A multigenerational, multiracial family legacy in Inglewood, Calif.

By Athena Mari Asklipiadis

Rick Kingi (Photo: Kim Kingi)

Ricardo Jiro Kingi, better known as Rick Kingi, is a 9th degree Kajukenbo grandmaster. For more than 50 years, Kingi has been studying and teaching Kajukenbo in the Los Angeles area.

Kajukenbo, or 垂姜怠垮扁很 in Japanese, is a hybrid martial art that originated in Hawaii. The name of the fighting style comes from a mix of multiple disciplines: KA(rate)-JU(do) and (jitsu)-KEN(po)-BO(xing).

In the late 1950s and early ’60s, when Kajukenbo made its way to California from Hawaii, Kingi and his brothers were some of the first to learn this unique fighting style in Los Angeles. From humble beginnings, learning and teaching in people’s garages, Kingi soon realized he had bigger dreams of wanting to open up his own school.

So, in 1981, he did just that when he found the perfect location for his studio in Inglewood, Calif. Since then, the school has continued to grow, amassing hundreds of pupils through the years — young, old, female, male and of every heritage one can think of.

The diversity in the school is a reflection of the Kingi family, who themselves are a mixed-race family with deep roots in both Japanese American and African-American history.

Kingi’s surname is from his late grandfather’s first name.

Genevieve Beckham Kingi and Inomata Kingi (Photo: Courtesy of Pure Winds Bright Moon)

Born in 1885 in Niigata, Japan, Kingi’s grandfather, Kenji Inomata, came to the U.S. as a young man and later enlisted in the Navy in 1906. While giving his name to the recruiting naval officer, he stated his last name first and his first name last, as many Japanese do.

This thus created paperwork and official documents from then on stating Inomata as his first name and Kingi (misspelled from Kenji) as his last name.

From then on, the family name in the U.S. was altered to Kingi. Inomata later married a mixed-Creole woman he met while serving in Pensacola, Fla.; the couple would together go on to have seven children (all given Japanese names), including Rick Kingi’s father, Inomata Kingi Jr.

Being an interracial couple in the early 1900s was not easy for Kingi’s grandparents, as both Asian Americans and African-Americans were regarded as second-class citizens at the time. But through the rough moments in history, Jim Crow laws, segregation and World War II, the Kingi family persevered and not only survived — they thrived.

Rick Kingi’s mother was a beautiful singer named Agustina Andrade, who performed with Jazz greats in the Los Angeles area and in Bakersfield, Calif. Despite her enormous talent and beauty, she was often ushered through the back door rather than the front of night clubs because she was black.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Kingi’s family would have been subject to the same regulations as all people of Japanese ancestry were at the time, having to forcibly report to a relocation center and be sent to an American concentration camp.

But that wasn’t the case for the Kingi family.

Due to the esteemed positions Inomata Kingi Sr. had held with the Navy as a steward who attended high-ranking officials, he was given an exemption, and the Kingis were not forcibly sent to camp.

Instead, they remained in Los Angeles. But not being in camp did not spare them any ill treatment. Harassment by the community was ongoing, as well as discrimination in regards to employment and subsquential lay offs due to the fact that they were of Japanese heritage.

During this time, the Kingis pleaded with the government at the state and federal levels to be treated fairly — much to no avail.

When reflecting on the moment all the Japanese left their neighborhood for camp, Takashi Kingi (Rick’s uncle) remembers the sad imagery of missing neighbors and friends and witnessing the looting of Japanese families’ left-behind belongings.

“My father was extremely hurt by all this,” Takashi Kingi recalled in an excerpt of “Pure Winds Bright Moon,” a book written by Kinji Inomata about the life of Inomata Kingi Sr. “Particularly in light of being a 30-year retired United States Navy man who had given most of his life to the service of his adopted country. He was traumatized and yet never spoke badly about the situation to any of us.”

The level of determination and strength Inomata Kingi Sr. demonstrated is the same work ethic the Kingi family lives by today.

Rick Kingi’s dedication to Kajukenbo and his community furthers his family’s rich legacy of duty and service. Kingi’s Kajukenbo is not just a school to learn fighting techniques, it is also referred to often as a family or ohana (Hawaiian for family).

“This school has been a benefit — it’s created an entire bond for our whole family,” said Rick Kingi. “We can care less if a person wins a tournament — the whole thing is about building character, about learning respect.”

Besides martial arts, the school has a mentorship program that offers teenagers the opportunity to meet various professionals in careers of their interest. They also “unplug” the kids, taking them camping sans cell phones. This type of training and encouragement has led to the school’s successful alumni roster of pro athletes, law enforcement, lawyers, doctors and noteable folks including David J. Johns, who served under President Barack Obama as the first executive director of the White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for African-Americans.

Being a part of Kingi’s Kajukenbo is also about celebrating diversity. Seeing the rainbow of ethnicities in the Kingi family and among the students enrolled there is a refreshing thing to see. But sometimes, being prideful of one’s Japanese heritage can be a challenge for others to grasp if one doesn’t necessarily look it.

Rick Kingi reflected on times when his Japanese-ness has come into question. When his daughter, Kim, won a Japanese baby pageant, his wife, who is Chinese American, was asked if she was Japanese, and she said no, explaining that her husband was.

Some minutes later, Rick Kingi came in and after taking a look at him, the officials told him he had to go home to get his birth certificate in order to prove his identity and ethnicity. With good humor, he laughed and said that two weeks after winning that pageant, Kim also won a black baby contest as well!

Other situations would also come up while Rick Kingi was teaching. Often, new students or visitors would ask where the master was, assuming he was not him. He has even been told directly that he couldn’t be trusted as a black martial arts instructor, implying that an Asian master would be more credible. But regardless of his acceptance (or lack thereof) by certain people, Rick Kingi remains authentically proud of everything he is — “I love my blend,” he said proudly.

Having Japanese roots is something the Kingi family has always been extremely proud of. Many in the family don their mon (Japanese family crest), which is tattooed on them. And operating the family’s Kajukenbo school has been a great source of cultural pride within itself.

The style of martial arts honors many traditional Japanese standards. Kingi shared that “mentally, Kajukenbo will teach you discipline, respect, concentration, patience, self-control, courage, self-confidence, perseverance and humility.”

He went on to continue, “I tell them to do everything they can to avoid a fight if possible, and that it takes a much stronger person to walk away from a fight than to fight.”

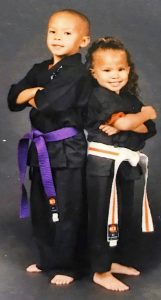

The next generation of Kingi’s Kajukenbo students. (Photo: Kim Kingi)

Kingi’s Kajukenbo is now mostly run and led by Rick Kingi’s youngest son, Robert, who has been on the mat since he was in diapers or perhaps even before then.

His family jokes it was a family obligation to take classes, and that they had “no choice,” but Rick Kingi proudly shares that now that his kids are grown, they have all thanked him for the lessons and trainings they were brought up with, which they now see gave them so much more.

“It’s beyond just a school, it’s beyond just getting a belt — a belt doesn’t mean anything, it’s what you do with it afterwards,” said Rick Kingi.

To learn more about Kingi’s Kajukenbo, visit kingikaju.com. And more information about the Kingi family can be found in the book “Pure Winds Bright Moon: The Untold Story of the Stately Steward and His Hapa Family Beautiful” by Rick’s brother, Kinji Inomata.

This article is part of a series on South L.A., so stay tuned for the next installment!

Athena Mari Asklipiadis, a Hapa Japanese L.A. native, is the founder of Mixed Marrow, a filmmaker and a diversity advocate.