Hawaii JACL’s Jacce Mikulanec contemplates the solitude of Topaz. (Photo: Rob Buscher)

JACL National Convention attendees visit the former site of the Topaz Relocation Center and Topaz Museum, a testament to all that has been overcome in the years since the incarceration era.

By Rob Buscher

On the Sunday after the JACL National Council concluded its official business, a hundred or so convention attendees had the opportunity to visit the former site of the Topaz Relocation Center. For many, this would be their first visit to an incarceration site, while others were visiting the place they used to call home.

Our daytrip consisted of a visit to the Topaz Museum, where we were greeted by museum staff and treated to a short video presentation about the history of Topaz, followed by free time in the museum and a bus tour of the Topaz site.

Despite the intensity of debates on the council floor at this year’s National Convention at the Little America Hotel in Salt Lake City, all divisions ceased to exist as our community gazed upon the barren desert plain.

A reconstructed barrack (Photo: Rob Buscher)

Unlike Heart Mountain and some of the better-preserved camps, the Topaz site is completely devoid of structures — save for the poured concrete foundations that the barracks once rested upon. It was painfully clear how inhospitable this desolate climate must have appeared to its population of Japanese Americans who mostly hailed from the San Francisco Bay Area.

Our tour guide happened to be a descendant of businessman Nels Petersen, the man who lobbied the War Relocation Authority to have an incarceration camp built in the region. In light of the bleak economic prospects that had plagued the small town of Delta, Utah, since the Depression era, Petersen believed that building a camp nearby would lead to prosperity.

After meeting with WRA officials in San Francisco, Petersen convinced them to purchase nearly 10,000 acres of land from local farmers in addition to 9,000 acres of county-owned land. About 10 families were forced to sell their farms to the government because of eminent domain, which rounded out the total land acreage to about 20,000. Although the local farmers received payment, this created an additional resentment to the Japanese Americans beyond the already hostile climate of war hysteria.

Visiting the Topaz Museum was the highlight for many of the attendees, as its extensive collection of camp artifacts and two refurbished barracks give visitors a better sense of how life was lived in those dark times.

Topaz Museum (Photo: Toshiki Masaki)

Located about 10 miles from the Topaz site in the small town of Delta, one wonders if the site itself might be more impactful had the interpretive center been built on that land.

In this sense, the Topaz camp continues to provide a source of revenue to the people of Delta since there is little else that would attract an out-of-state visitor to the rural desert town.

Nevertheless, the exhibit display was a stirring and poignant reminder that extended beyond the platitudes of rhetoric that sometimes obscure the harsh realities of camp life.

According to statistics recorded at the museum, there were only six Japanese American families living in the town of Delta prior to World War II. Amidst the omnipresent anti-Japanese propaganda that preceded the wartime incarceration, the incoming residents of Topaz were viewed with distrust by many of the townspeople.

Although the local economy did begin to flourish from the construction boom, tensions were exacerbated when storekeepers could not keep up with demand as Japanese Americans were allowed day passes out of camp to go shopping for essentials that could not be bought in camp.

In a June 7, 1943, memo, Topaz Director Charles Ernst wrote about the “deterioration in the attitude of Delta people towards residents.” He explained that many of the townspeople saw its Japanese residents as scapegoats, stating, “For instance, if store-keepers run out of things, they explain this … by saying, ‘The damn Japs have bought us out.’ Shopkeepers hide some things under the counters … when residents are permitted to be in Delta in order to save them for the Caucasian customers.”

A pictorial history of Topaz is displayed inside the museum. (Photo: Toshiki Masaki)

Others in Delta viewed the Topaz residents with suspicion simply because they lived behind barbed wire, figuring that they must have done something to deserve their incarceration. Another museum panel included a recollection from Delta resident Callie Morley of rumors that “the Japs had bought every butcher knife in town and were planning an uprising.”

Perhaps this paranoia contributed to the killing of Issei James Hatsuaki Wakasa, 63, by military policeman Pvt. Gerald Philpott, who claimed that Wakasa was trying to escape on April 11, 1943. Making matters more controversial, no warning shots were fired, and the only witness was another guard.

Their account does not correlate with the evidence recorded in the official police report, which showed that Wakasa was shot in the chest facing toward the guard tower and was actually several feet within the perimeter fence.

Mass protests erupted, and all work stopped at Topaz until after Wakasa’s funeral was held. Despite mounting evidence that Wakasa was not trying to escape, Pvt. Philpott was found not guilty and transferred to a different post.

In the aftermath of this tragic event, security lessened, and the Topaz residents were given additional freedoms to come and go from camp.

Incarceration survivor Ben Takeshita recounted a fond memory of collecting topaz crystals in a nearby cave that he and some friends snuck off to one day. Feeling tired from their afternoon excursion, the boys flagged down a passing MP jeep who gave them a ride back to camp.

As time passed, the tensions between the Delta townspeople and Topaz residents lessened, with many of the townspeople finding employment related to the camp. Some even took sympathetic views to the plight of Japanese Americans, such as Delta teacher Melvin Roper.

Seeing the barracks being built, Roper observed that they were “very inappropriate for the type of weather that these people were to live in.” Roper went on to oversee the industrial arts program at Topaz High School, coordinating auctions of his woodshop students’ work to help young Nisei earn money in camp.

Another teacher, Louise Adams, helped to organize goodwill exchanges between Delta High School students and those at Topaz. One highlight was the musical production “Hi Neighbors,” which was performed by Topaz residents at Delta High School, including actor Goro Suzuki, who was featured in a prominent role.

One of the museum staff recalled a story from an elder Delta resident who remembered the reactions from a tear-filled audience at the irony of Suzuki singing “America the Beautiful” as part of that production, knowing he would return to his home behind barbed wire that night.

Suzuki would later go on to star in the 1961 film adaptation of “Flower Drum Song” as nightclub owner Sammy Fong under his stage name of Jack Soo.

Alas, while Suzuki was able to find success in his career as an actor (including a series regular role as Det. Nick Yemana on the ABC police comedy “Barney Miller”), he did so under an alias that hid his Japanese ancestry.

Like most topics in the Nikkei community, the layers of detail and nuanced differences between camp experience continues to amaze. As much sadness and trauma resulted from the incarceration at Topaz, so did beauty and joy.

The most striking example of the positive aspects of camp life in Topaz was the Topaz Art School, which was established by University of California, Berkeley, Fine Arts Professor Chiura Obata.

A career artist who left Japan at the age of 17, Obata had worked in newspaper and magazine illustration before joining the painting faculty at Berkeley in 1932. Although he had the opportunity to leave California during the “voluntary evacuation” to join his son, Gyo, in St. Louis, Obata chose to remain with his community and help them endure what would come through the pursuit of art education.

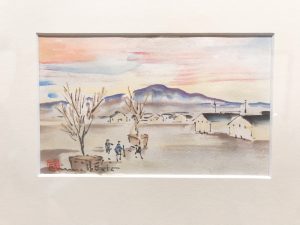

A greeting card water color by Chiura Obata

In the five months that Obata was held at the Tanforan Assembly Center while Topaz was being completed, he managed to establish an art school that taught more than 600 students ranging in age from 6-70. The school featured more than 23 subjects that included figure drawing, commercial art, architectural drawing, fashion design, sculpture and still life — in addition to more traditional Japanese mediums like ikebana.

Speaking of his motivations for opening the school, Obata wrote, “Art training gives calmness … [while making art] the mind is concentrated to a single objective. We only hope that our art school will follow the teachings of this Great Nature, that it will strengthen itself to endure like the mountains, and, like the sun and the moon, will emit its own light, teach the people, benefit the people and encourage itself.”

Later when they were moved to Topaz, the paintings and drawings created by Obata’s students would be some of the only recorded images made by Japanese Americans in that camp, as access to cameras was highly restricted.

From both his writings and artwork produced during the incarceration, it is clear that Obata viewed his art as a means of perseverance in this time of tribulation.

In a more pointed statement about the impact of art in weathering the incarceration experience, Obata wrote, “We will survive, if we forget the sands at our feet and look to the mountains for inspiration.”

Yet despite his best efforts to forget, amidst the tension of the loyalty questionnaire, Obata was physically attacked by an extremist who thought him to be a government spy because of the special privileges granted to him by camp administrators. After two weeks spent recovering in the Topaz hospital, Obata was released for his own safety and sent to live with his architect son in St. Louis.

Despite Obata’s departure, the Topaz Art School continued to thrive until the camp’s closure, under the direction of Matsusaburo George Hibi, another talented painter who helped Obata open the school.

Hibi wrote during his time in camp, “Let us art lovers keep on in the study of art tirelessly wherever we shall relocate or whatever fate shall face us… . I am now inside of barbed wires but still sticking in Art — I seek no dirt of the Earth — but the light in the star of the sky.”

Hibi’s wife, Hisako, was also a painter who taught at the school. She recalled one class during a particularly cold winters day, “Water turned to ice on the watercolor paper while I was painting… . Shivering, we kept moving our brushes and persisted in painting.”

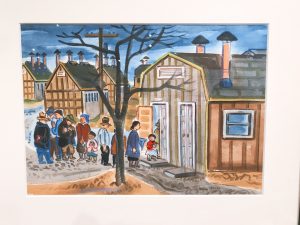

A Mine Okubo oil painting

Over the three years the school was in operation, more than a dozen instructors shared their time and talents with aspiring artists, including another Nikkei artist luminary, Mine Okubo.

Best known for her illustrated memoir titled “Citizen 13660,” Okubo was also involved in both the Topaz Times newspaper and TREK, a literary journal published in camp.

Reflecting on the role of art in documenting their experiences in camp, Okubo wrote, “Cameras and photographs were not permitted in the camps, so I recorded everything in sketches, drawings and paintings.”

Okubo’s illustrations of the daily hardships of camp life were among the first images shown to the general public depicting the realities of the incarceration, which were published in the April 1944 issue of Fortune Magazine.

After being hired to illustrate a special feature on the domestic homefront of wartime Japan, Okubo moved to New York City, where she worked for Fortune Magazine for several years. At least in her case, art would prove to not only be a method for enduring the indignities of wartime incarceration, but also a viable means to overcome them as well.

They say most great art comes from a place of pain. The art that came from the Topaz residents speaks to the incredible trauma they underwent as a collective community, but also stands as a lasting testament to the strength of their resolve to overcome the many injustices of that era.

It also reminds us of the important role that art has played in our community’s past and provides compelling motivation for incorporating the arts into our present-day advocacy efforts.