Modest in life, a passed-over Frank Watanabe is finally recognized after his death.

By P.C. Staff

The July 13, 1973, Associated Press dispatch from Overland, Mo., described a conflagration as follows: “A fire on the sixth floor of the massive Military Personnel Record Center raged out of control in this St. Louis suburb Thursday night. Weary firemen continued efforts to save military files housed in the building.” Items not burned or damaged by the flames sustained water damage.

The article also reported, according to the General Services Administration, that the repository contained the “records of 56 million members and former members of all branches of the military,” including “about 9 million from World War II.”

In addition, it noted that the “loss of the records is expected to create problems that could take years to solve.”

For the family of the late Frank Watanabe, that assessment proved to be all too true.

◊◊◊

Frank Watanabe, in uniform, with parents Risaku and Teruyo Watanabe. (Photo: Courtesy of the Watanabe Family)

Shunso Frank Watanabe, who died at 92 on June 18, was born on April 9, 1927, in Reedley, Calif., to emigrants from Japan’s Hiroshima-ken. A mechanical engineer by training who spent decades in Detroit’s automotive industry, his name is on more than 150 patents, many in control systems for electronics.

Both of his daughters, Alysa Sakkas and Kari Aguinaldo, characterize him as brilliant, yet humble. His interests were wide-ranging, from the practical, as evidenced by his many patents, to the philosophical and spiritual, especially in his twilight years.

Like thousands of other first-generation Japanese and their second-generation American offspring living along the U.S. West Coast with the advent of World War II, the Watanabe family was removed from their home to be incarcerated in one of 10 U.S. concentration camps, in their case, the Gila River War Relocation Authority Center in Arizona.

Before that, the young Watanabe learned to appreciate music. According to an autobiographical essay he wrote for a family member, he first learned the violin, then the trumpet.

“In the seventh grade, I became the solo trumpet in the school marching band and the first chair brass in the orchestra,” he wrote.

But Watanabe’s “consuming interest” as a boy was model airplanes.

He wrote, “I started building balsa stick and Japan tissue models from kits since I was 6 years old, and because I had no mentors, I learned to read the Model Airplane News hobby magazine and technical publications.

“By the time I reached the eighth grade, I was as familiar with advanced topics as the Davis laminar airfoil, which made the B-24 and P-51 American war planes great,” he continued in his essay. It was a hobby and aptitude that no doubt augured his future career as a mechanical engineer.

Before he would embark on that journey, however, Watanabe and his family would first need to deal with life at Gila River. With America’s entry into WWII, Frank’s father, Risaku, foresaw the imminent fate of West Coast ethnic Japanese and therefore made preparations.

“While facing the total devastation of the lifestyle he had built, his main concern was to keep the family together in one camp. He calmly sold the farm equipment, the family car and personal possessions,” Watanabe wrote of his father’s actions, including arranging in advance to have the Reedley branch of Bank of America hold his investment accounts and allow him to manage his checking account by mail, before becoming Family No. 40411.

Watanabe graduated from Gila River’s Canal High School, where he served as class president (“I made shambles of my office,” he wrote in his essay) at age 17, having already skipped two grades, according to Aguinaldo.

After graduation and with help from the Religious Society of Friends and after being cleared by the WRA, Watanabe enrolled at the University of Detroit.

“My camp life was ended by being launched into my new world by Quakers who enrolled me, a Buddhist farm boy, at an urban Catholic university by the authority of an almost-unknown government agency,” he wrote.

After just one year at the University of Detroit’s College of Engineering, the government would again intervene in his life when Watanabe was drafted into the Army.

◊◊◊

“When he was in the Army, his dream — he told my husband and I this — was to lead a tank battalion,” Sakkas told the Pacific Citizen.

Her father had high test scores and to reach this goal, he studied military strategy. But when he told his superiors of this aspiration, Sakkas said they told him, “We would never let someone like you do a job like that.” Translation: You’re Japanese, so you don’t get to do that.

Instead, Watanabe was sent to serve in the Military Intelligence Service to further strengthen his Japanese language skills in areas such as the translation of documents, serving as an interpreter or interrogating Japanese prisoners of war.

Sakkas said her father, however, didn’t want to join the MIS.

“He told us that during some of the testing, he would purposely try to score low because he was really hoping to get a different assignment,” she laughed. He did not get his wish.

Watanabe nevertheless completed the MIS training, going on active duty on Aug. 31, 1946.

“He used to say he was in the first graduating class of the Defense Language Institute in Monterey,” Sakkas said. Watanabe was honorably discharged on Dec. 5, 1946. It wasn’t a long stint — but serve he did.

After leaving the Army, Watanabe returned to Michigan’s University of Detroit and earned his bachelor’s degree. He then attended Wayne State University to obtain his master’s degree in mechanical engineering and went on to work for Kelsey-Hayes Corp., where he worked on the initial patent for the disc brake.

“He probably would have stayed with them for his entire career,” said Sakkas, “but they were swallowed up in a merger, and he lost his job in the process.”

Watanabe eventually found work at firms such as American Motors Corp., Bendix Corp., Rockwell International and the Ford Motor Co., where he was employed when he retired.

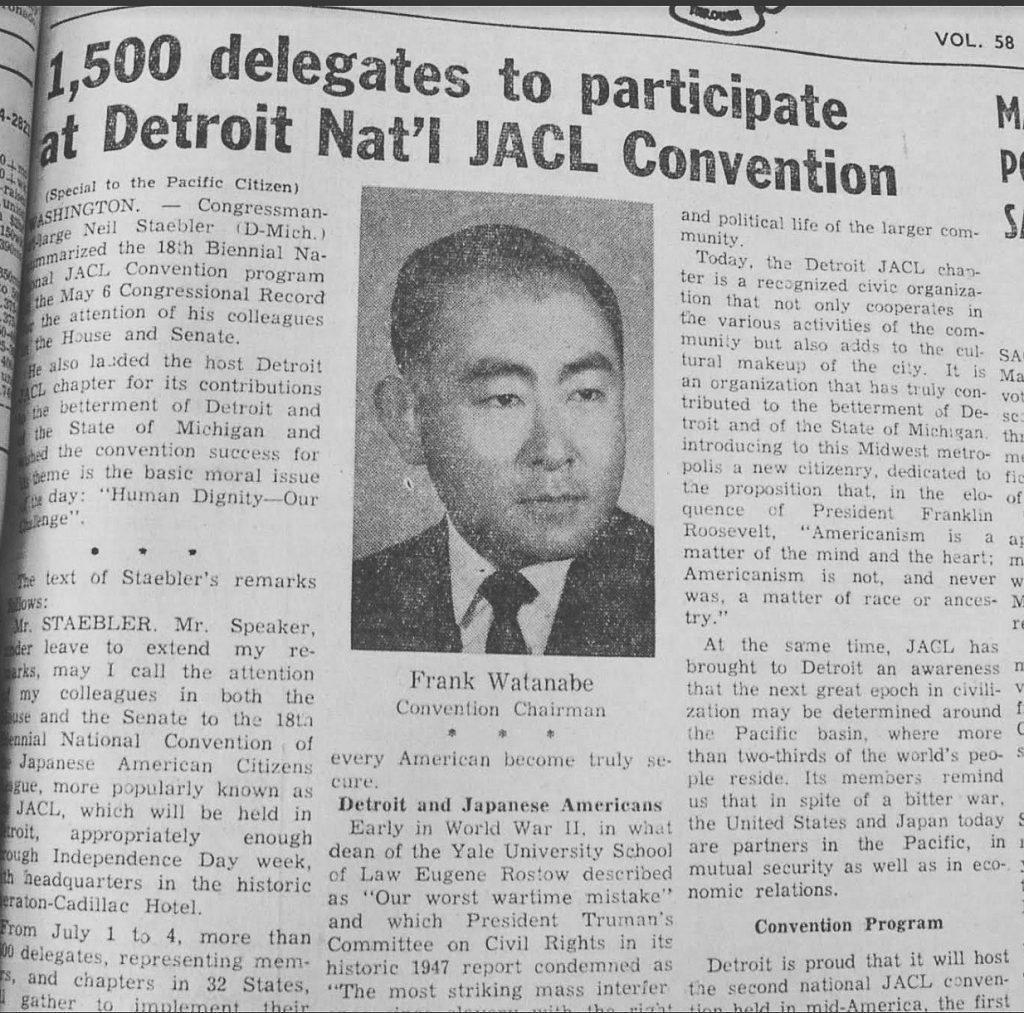

Frank Watanabe served as chairman of the 1964 JACL National Convention, as pictured here in a photo from the Pacific Citizen archive.

In 1961, he and Margaret Ueki were married. They later lived in Livonia, Mich., and raised their two daughters, Alysa and Kari. Watanabe was active in the Detroit JACL chapter, even serving as its president one year and chairman of the 1964 JACL National Convention.

When they were old enough, the sisters both moved to California, where they would spend their summers with relatives. According to Sakkas, after her father retired, Margaret said, “Now that you’re retired, what are we doing in Michigan, when both of our daughters live in California and we have two grandkids who live in California?”

Watanabe, however, loved Michigan and its four seasons and thought his family would return.

“My dad said, ‘Eventually, they’re going to move back to this house.’ And I said, ‘No, we’re not,’”said Sakkas. So, the Watanabe’s moved back to California in the early 2000s and found a house in Cupertino, when it was relatively more affordable than today.

◊◊◊

Nisei Soldiers of WWII Congressional Gold Medal

In 2010, President Barack Obama signed into law a bill that would award the Congressional Gold Medal collectively to the Nisei who served in 100th Battalion/442nd Regimental Combat Team and MIS during WWII.

Sakkas remembers talking about that development with her father: “So, when I heard about the Congressional Gold Medal was awarded, I asked him, ‘Are you going to get one?’ and he said, ‘No, no one’s notified me.’”

Sakkas insisted that he must be eligible, but her father played it off. She remembers him saying that maybe he didn’t serve long enough.

“He just kind of left it at that,” Sakkas said. Aguinaldo corroborated that conversation. “When my sister told him she wanted to research it, he said, ‘Aww, it’s so long ago, who cares? Nobody’s going to care,’” Aguinaldo said.

When Watanabe was approaching his 88th birthday or beiju, Sakkas decided to collect some memorabilia to celebrate it, and she contacted the Defense Language Institute. She thought, perhaps, she might be able to get a copy of his diploma.

She was taken aback to learn it had no records from the first two years of the Institute. Watanabe did mention, in passing, that there had been a fire that destroyed the records of many veterans. “I didn’t pursue it any further,” she said.

According to Sakkas, her father was very conscientious about his health and made sure to exercise to maintain it. But a couple of years after his 88th birthday, he encountered some health problems and needed in-home care.

“One of my friends said, ‘Your dad was a veteran. Well, my dad was a veteran, and he gets 40 hours of in-home care paid for. You should really look into whether your father is eligible for anything,” Sakkas recalled.

When she inquired with the Department of Veterans Affairs to see if Watanabe was eligible for any benefits, however, she was told it had no record of him ever having served in the military.

“I told my dad, ‘The VA doesn’t even have any record of your service,’” Sakkas said. But Watanabe did know exactly where his discharge documents were. Therefore, Sakkas sent a copy to the VA and was told that the records between a certain time period and part of the alphabet were lost in the 1973 fire. It therefore accepted as authentic the copy of Watanabe’s DD214.

“It dawned on me that that was the fire the guy (from the Defense Language Institute) was talking about, and that’s why my father was never recognized as being a member of the MIS,” Sakkas said.

◊◊◊

Sakkas later contacted the office of U.S. Rep. Ro Khanna, whose district includes Cupertino, Calif., to inquire whether her father was eligible for the Congressional Gold Medal and provided her father’s pertinent information.

Meantime, Watanabe’s health was deteriorating. Death came quickly and painlessly.

That same day, June 18, Sakkas received a call from Rep. Khanna’s office. “They called me literally two hours after he died to say, ‘We’re just getting back to you. It’s been a long time, but we figured out that your father did earn the Gold Medal, and so we’re wondering when we can present it to him.”

The Nisei Congressional Gold Medal was presented to Watanabe’s family at a Town Hall Meeting on Aug. 24.

Flanked by Rep. Ro Khanna, left, and Consul General of Japan in San Francisco Tomochika Uyama, Alysa Watanabe speaks at the ceremony where her father’s delayed Congressional Medal was awarded posthumously on Aug. 24.

“I felt like he was sending me a sign,” Sakkas said of a phone call she would then receive from Rep. Khanna’s office. “You’re the only one who cared about this. I don’t care about it, so he taps someone on the shoulder and says, ‘OK, you can call her now.’ ”

In retrospect, Sakkas realizes that her father’s situation, i.e., not being recognized because of the records fire from 1973 was unusual, but not necessarily unique, might prove valuable to others.

“My hope is that there are other people who find out that they have relatives who should have received this award but did not,” Sakkas said.

One remaining mystery is her father’s first name. Although he mainly went by his middle name, Frank, his first name is spelled Shunso. But Sakkas found that in a book on Japanese American veterans and engraved on a wall at the Defense Language Institute in San Francisco is the name Shunzo F. Watanabe.

Meantime, Sakkas looked on her father’s birth certificate, where it’s spelled Shiyunso Watanobe, with both names mangled.

Unlike the outcome on the Gold Medal, the reasons behind the mysterious spellings may never be completely solved.