A skeleton ‘found’ on Mount Williamson might be ‘missing’ WWII Manzanar camp incarceree Giichi Matsumura

By Charles James, Contributor

[Editor’s note: Subsequent to the publication of this article, the Inyo County Sheriff’s Office and the National Park Service confirmed that the found remains were those of Giichi Matsumura.]

Nothing demonstrates just how unpredictable or dangerous a mountain can be better than the recent discovery of skeletal remains on Oct. 7 in the Williamson Bowl by two recreational hikers on Mount Williamson, located 210 miles north of Los Angeles in the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

The mountain has the second-highest peak in California at 14,375 feet and rises some 9,000 feet above the floor of the Owens Valley. Whatever a hiker or climber is looking to experience in the great outdoors, stumbling across human remains is generally not one of them. The “find” set off an avalanche of interest across various news media, and there will be more to come when the “mystery” is finally solved.

While mountains are beautiful, alluring and even majestic, they also can be dangerous, life-threatening and, occasionally, even fatal to those that venture onto them. Danger from mountains come from sudden, unpredictable and often severe, even freakish changes in weather. Thunderstorms, lightning storms and even out-of-season snowstorms are always a possibility.

The “find” of the skeleton by the two hikers, Tyler Hofer and Brandon Follin from the San Diego area, was described on the California Mountaineering Group Facebook website. Hofer posted that the discovery was “something truly unique … and pretty crazy.”

Hofer described how they were “slightly off course” in the Williamson Bowl, just above the fourth lake, looking for a path to the summit, “when I looked down and saw something strange underneath a small boulder. I thought it looked like a bone of some kind, and after closer inspection, it was indeed a human skull. We started to move the rocks aside, and it turns out there was an entire human skeleton buried in the rock field.”

It was clear to Hofer and Follin that “the body had clearly been there a while as all of the clothing had decomposed,” and the only things left “were the bones, shoes (which were rock climbing shoes) and a leather belt.” He went on to say that the body “appeared to be in a burial pose.”

Hofer went on to write that “after summiting Mt. Williamson, we called the Inyo County Sheriff Department,” who at first suspected foul play might have been involved; an idea quickly discounted by the Sheriff’s department.

The Sheriff’s Office downplayed the idea of foul play because the department had no reports of anyone gone missing from that area for many years, and from the description of the skeleton, it was clear that the bones were quite old, as all of the clothing had disintegrated.

When contacted by the Pacific Citizen, the Sheriff’s Public Information Officer, Carma Roper, cautioned that “DNA tests were being taken on the bones as part of the investigation, and it is a process that takes two to four months, so it could be February of next year before we have an official finding. Until then, we don’t know who it is, nor will we speculate on who it might be. We will wait for the DNA results.”

Giichi Matsumura

The widely reported news of the skeletal find fueled speculation immediately when posted online and locally with those familiar with the history of the area. Many recalled that 47-year-old Giichi Matsumura, an incarceree from the World War II Manzanar Concentration Camp, went missing on Aug. 2, 1945, on Mount Williamson. He was eventually found and reburied on the mountain. The camp, located in the shadow of Mount Williamson, was within a reasonable hiking distance of its lakes, where Matsumura had gone missing.

Mount Williamson was a popular escape destination for fisherman incarcerated at Manzanar during the war, said Cory Shiozaki, the filmmaker of the feature-length documentary titled, “The Manzanar Fishing Club.”

The documentary, written by Richard Imamura, is described as the story “through the eyes of those who defied the armed guards, barbed wire and searchlights to fish for trout in the surrounding waters of the Eastern Sierra.”

Using personal stories of camp incarcerees, it was the first film to go beyond the confinement itself, and instead highlight values — courage, responsibility and cooperation — that enable the human spirit in which “the simple act of fishing represented freedom and defiance to those that had unfairly taken their freedom from them.” (Note: More information on this 2012 documentary can be found at www.fearnotrout.com.)

According to Shiozaki, on July 29, 1945, “Matsumura tagged along with a group of six to 10 other fishermen who were looking to catch golden trout, which are only found at very high elevations.” Matsumura, who was also a watercolorist, worked in one of Manzanar’s mess halls. He was reported missing after separating from the group after electing to stay behind at a lake along the way to sketch or paint, while the others continued up to the next lake to fish.

Although it was still summer, there was a freak blizzard that forced the fisherman to find refuge in a cave to wait out the snowstorm. After the weather cleared, the group went back for Matsumura, only to discover they could not find him.

They searched the area and concluded that he had likely returned to Manzanar on his own. Once back, they discovered that he had not. Two search parties were sent out to look for him over several days. They found Matsumura’s sweater, which was positively identified by his wife, Ito. His story was reported on the front page of the Manzanar Free Press in its last edition, which was published on Sept. 8, 1945. It reported that he had “died of exposure.”

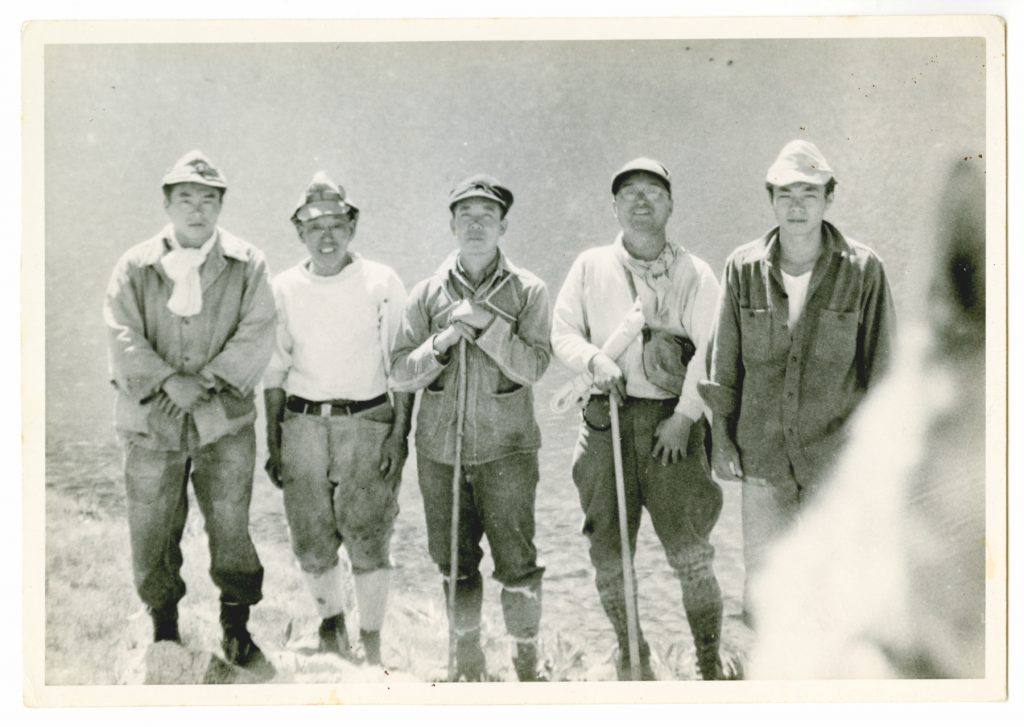

The search party that found Giichi Matsumura’s remains. Pictured (from left) are Masaru Matsumura, Giichi’s oldest son; friend Heihachi Ishikawa; Tadao Matsumura, Giichi’s brother; friend Frank Hosokawa; and Tsutomu Matsumura, Giichi’s second-oldest son. (Photo: Danny Hashimoto)

A month after Matsumura went missing, Mary DeDecker of Independence, Calif., a local botanist and avid outdoorswoman, was picnicking on Mount Williamson when she noticed a tree branch or pole protruding from a pile of rocks. She said that it struck her as unusual because high elevations are typically well above the tree line.

Curious, she went to investigate and discovered the missing Matsumura’s remains. She knew immediately who it was, as his disappearance was well-known in the local communities. DeDecker covered his remains with flat rocks to protect them and returned home to report it.

A burial detail that included two of Matsumura’s sons was dispatched to the location, and the body was officially reburied on the same spot. Back then, when someone died in a remote location such as in the mountains in difficult terrain, their remains were often buried there.

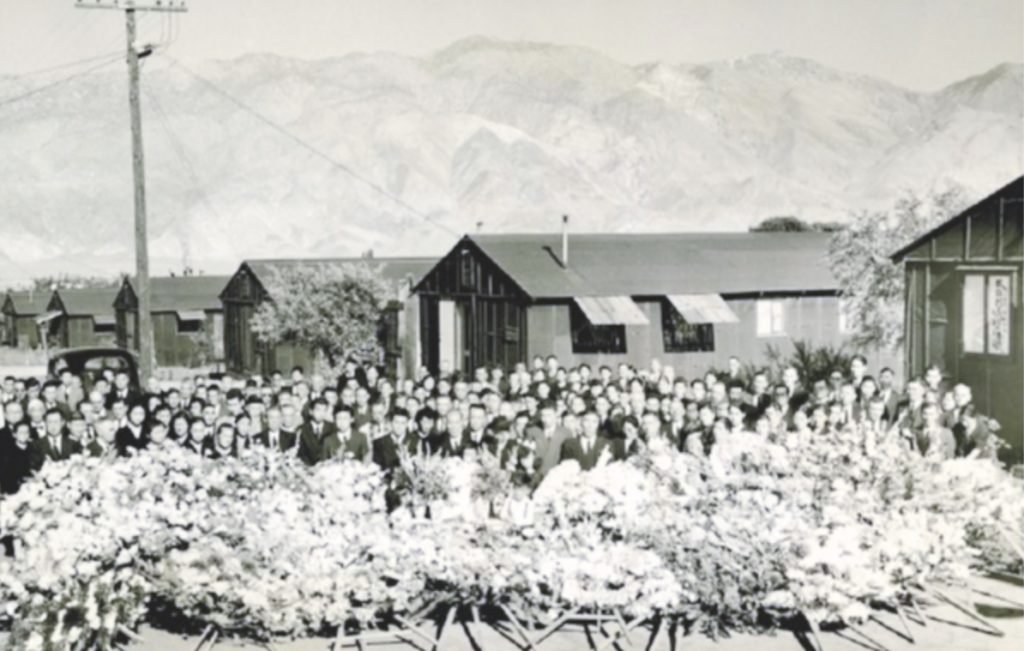

Giichi Matsumura’s funeral service at Manzanar. (Photo: Courtesy of “Manzanar Fishing Club”)

Executive Order 9066, issued in 1942 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt following the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japan, allowed the United States government to order the forced evacuation of more than 120,000 men, women and children of Japanese ancestry to leave their homes and be forcibly incarcerated inside military-style camps in remote areas around the U.S.

Giichi Matsumura, his wife, Ito, their three teenage sons (Masaru, Tsutomu and Uwao) and young daughter, Kazue, along with a brother, Tadao, and his father, Katsuzo, were forced from their homes in Santa Monica, Calif., and sent to the Manzanar War Relocation Center.

The Manzanar War Relocation Center, as it was then called, was one of 10 American concentration camps where Japanese American citizens and resident Japanese aliens were incarcerated during WWII. All of the Matsumura children were U.S. citizens, as were most adults and children placed in the camps. Today, it is considered one of the most egregious human and civil rights violations ever taken against any American citizen by his/her own government.

Those forced into the camps lost their property, which included their homes and furnishings, businesses, cars and even pets, along with their jobs and source of income. Toward the end of 1945, there were still many incarcerees still staying at the camp. Although free to leave, many simply had no place to go, having lost everything during the forced removal. Adding to their concerns was the fear that they might become victims yet again of racism and violence from their fellow Americans should they return to their former communities.

It may well be that after 74 years, the remains of Giichi Matsumura may have once again been “found.” It is being said that he was “lost once and found twice.” However, National Park Service Archaeologist and Cultural Resource Program Manager at the Manzanar National Historic Site, Jeffrey Burton, holds a different view.

Burton says that there were many people working with the California Bighorn Sheep Zoological Project Area on Mount Williamson who knew exactly where Matsumura’s gravesite was located. From 1981 until 2010, the project area was closed to the public to safeguard Bighorn Sheep, a federally protected species. Matsumura’s gravesite was located within this restricted area, and the gravesite was respected and left undisturbed.

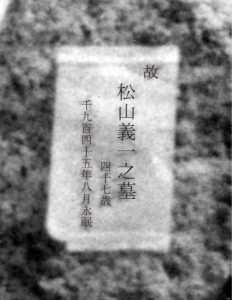

Translated: Deceased A Grave for Giichi Matsumura Age 47 1945 August Rest in Peace.

Burton provided the Pacific Citizen with several photos from the original search and burial parties, including a photo of the cairn, which had a note attached to it. The note, written in Japanese, read: “He found his freedom in the mountains.”

What comes next depends on the official DNA results on the bones. If it indeed proves to be Giichi Matsumura, as suspected by many following this case, his remains will be turned over to family members to be buried alongside his wife, Ito, who died in 2005 at the age of 102. She is buried at a cemetery in Santa Monica, so in that sense, his remains will be returned home.

If it is not Matsumura, the authorities will have another mystery on their hands.