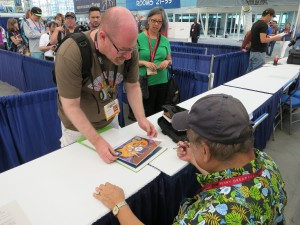

Willie Ito giving a fan an autograph with ‘Lady and Tramp’ at the San Diego Comic Con International where he received the Inkpot Award. Photo by Tiffany Ujiiye

Willie Ito is awarded the Inkpot Award at this year’s Comic Con International, where he also announces the premiere of his latest book ‘Kimiko’ in 2015.

By Tiffany Ujiiye, Assistant Editor

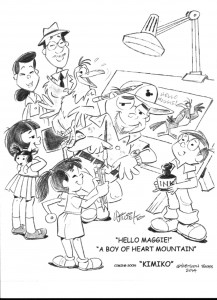

An illustration by Willie Ito that includes characters from his projects, including his newest character Kimiko.

In the sea of costumed Batmans, Super Marios, Sailor Moons and all things pop culture last month was an 80-year-old man with a sun-faded Disney baseball cap in a patterned green Hawaiian shirt and slacks.

At this year’s 2014 Comic Con International in San Diego, Calif., artist Willie Ito was awarded the Inkpot Award on July 26 for his 60 years of achievement and animation. The Inkpot Award is an honor given to professionals in the fields of comic books, comic strips, animation, science fiction and other related areas of pop culture. Past recipients include such icons as Ray Bradbury, Will Eisner, Hayao Miyazaki, Stan Sakai and Steven Spielberg, to name a few.

“I always thought that possibly one day I might deserve it,” Ito said of his honor. “I truly never expected it.”

Since 1991, the San Diego Convention Center has housed Comic Con International, the world’s largest hive of all things pop culture, dedicated to creating awareness and appreciation for the genre. These platforms include anything from comic books to full feature films to toys and everything else in between. The four-and-a-half day event swallows downtown San Diego in art and media, attracting more than 130,000 attendees from all over the world. Yet, in the middle of the foot traffic hovering over the latest “Avengers” film or AMC’s “Walking Dead” panel was a remembrance to animation’s golden years.

Leslie Combemale of ArtInsights, a gallery specializing in animation and film art located in Virginia, discussed Ito’s life, revisiting his childhood at Topaz Internment Camp in Utah and his time after World War II as an animator.

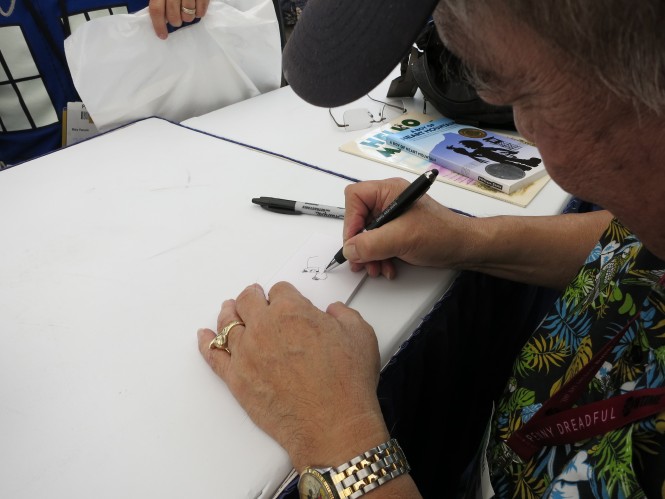

Willie Ito at his San Diego Comic Con booth where he signed autographs and met fans after his spotlight discussion. Photo by Tiffany Ujiiye

During his career, Ito helped animate such renown projects as the famous spaghetti scene in Walt Disney’s 1955 animated film “Lady and the Tramp” with mentor Iwao Takamoto and the 1957 short “What’s Opera, Doc?” during his time at Warner Bros. under the direction of Chuck Jones. Later, Ito went on to animate “The Beany and Cecil Show” with Bob Clampett and then “The Flintstones,” “The Jetsons” and many other cartoons at Hanna-Barbera.

Today, Ito is working on his third book, which is titled “Kimiko,” about a Nisei girl living in San Francisco. The children’s book is a parallel to Ito’s life experience growing up in Japantown and his memories from Topaz.

“I want to talk about Topaz,” Ito explained. “You don’t always hear about Topaz, and so it made sense to do a book about it.”

“Kimiko” will premiere in 2015 at the opening of the Topaz Museum and Education Center in Delta, Utah. Ito, along with other former internees, attended the museum’s groundbreaking ceremony on Aug. 4, 2012, and he plans on returning for its opening. No official date has been announced yet, but Ito expects to finish “Kimiko” in time for the opening.

Willie Ito and Leslie Combemale of ArtInsights during Ito’s spotlight discussion at the San Diego Comic Con. Photo by Tiffany Ujiiye

Back in 2005, Ito and Shig Yabu, a childhood friend, collaborated on creating and publishing “Hello Maggie” and “A Boy of Heart Mountain” under Yabitoon Books, a publishing company the collaborators created themselves. Both tomes drew from their creators’ experiences of being incarcerated during WWII and the need to further educate children on what life was like during this time.

Today, readers can find these books on Amazon.com and at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center in Wyoming, the Japanese American Veterans Assn. in Virginia and other Japanese American booksellers and museums.

While “Kimiko” is his latest project, Ito’s love for animation and drawing started almost 75 years ago in San Francisco at a local theater in Japantown.

“This one day I truly had an epiphany,” Ito explained to the Comic Con audience while accepting his award. A 5-year-old Ito and his father, Will Katsuichi Ito, had gone to see Disney’s “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.” The film premiered in December 1937 in full Technicolor and was a boxoffice success, becoming 1938’s top-grossing sound film.

“I was sitting in this theater, and in living Technicolor came seven little men marching across the screen. My fate was sealed, and after the film, my father took me to the Woolworth store and he bought be a Dopey bank,” Ito recalled.

To this day, Ito has the Dopey bank that he was unable to bring with him when he and his family were incarcerated at Topaz. His memories of life in camp are still very vivid in his mind.

Ito first learned about the war on a Sunday afternoon when he, his aunt and his future uncle were returning to San Francisco after spending a day at the beach in Santa Cruz. Ito saw the armed guards with their weapons, checking each car entering the city and asking for identification.

“I thought, ‘Gee, what’s going on?’” Ito explained. “Finally, we saw the newsstands and it read, ‘War.’ I never knew what that word meant until I found out that Pearl Harbor was attacked by the Japanese.”

A profound hysteria created by inflammatory journalism spread fear in the U.S., leading President Franklin D. Roosevelt to sign Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942. The exclusion act incarcerated Japanese Americans from the West Coast outside of Hawaii and forced them into detention centers within the western United States. As a result, more than 120,000 Japanese Americans were forced to leave their homes and businesses behind. For Ito, it was not just all of the above but also his Dopey bank.

“(Before the war) I put the Dopey bank on my dresser, and every morning I would see my Dopey. His character made an impression on me, and it was a magnificent feeling,” Ito said. “It was one of the most valued things I had, and suddenly, I couldn’t take it with me. We could only take what we could carry in two hands.”

Ito continued his love for animation in camp, drawing on Sears, Roebuck & Co. and Montgomery Ward & Co. catalogs that his family received every three months. Within the catalog margins, Ito would draw Disney characters, including Dopey, in random sketches and then animate them by flipping the pages with his fingers.

After the war, Ito’s family returned to their former home in San Francisco, which was kept safe thanks to a Chinese American family. Upon first re-entering the house, Ito ran upstairs to his bedroom, where he found his Dopey bank still sitting on the dresser.

Ito’s 45-year animation career began several years later when he landed his first job at age 19 at Walt Disney Studios in Burbank, Calif. During that time, he was attending the Chouinards Art Institute in Los Angeles and worked as an apprentice and inbetweener, a job title given to animation students. It was at Disney that he assisted the production of “Lady and the Tramp” and later 1967’s “The Jungle Book,” mentoring under Takamoto.

“They called in an Asian guy to see my portfolio, and I really needed that,” Ito said about his Disney job interview. “I had just left the comfort of Japantown and now I’m here in Hollywood. It was a different world with not a lot of Asian people, and even though it was only nine years after the war, I didn’t know what reaction I would get. When I saw Iwao, the anxiety was drained.”

The apprentice-mentor relationship was as rewarding as it was challenging for young Ito.

“Iwao would chop up my drawings, criticize it and change it. He was such a perfectionist — he wanted to see perfection,” Ito remembered. “I would go back to my desk totally devastated, and I thought I should’ve taken my father’s advice.”

Ito’s father had suggested early in his career that Ito attend barber college to obtain a license should his animation job fall through. Although his family was supportive of his time in Hollywood, they were always concerned about the late nights Ito spent in the studio.

“But I grew a thick skin,” Ito said with a smile. “This businesses isn’t for everyone, and a lot of people hated it, but I always saw it as a learning experience. The criticism made me a lot stronger.”

After a year and a half at Disney, Ito was hired at Warner Bros. He then moved to Hanna-Barbera for 14 years, working with Clampett before making another jump to Sanrio.

The comic strip department was dissolved when Ito returned to Disney in (need date). He had decided to put a pause on his animation work and spent 23 back at Disney until he retired in (need date) as the Director of Disney Character Art International, working with international offices to mentor artists and making sure the integrity of Disney characters were maintained.

Now retired and working on “Kimiko,” Ito is also working on a coloring book for “Hello Maggie” and “A Boy of Heart Mountain.” Today, he lives with his wife, Rosemary, in Monterey Park, Calif. Together, they have four adult children, six grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. His house is full of cartoon memorabilia and his beloved Dopey bank.

Ito’s love for animation, Dopey and life continue, and the stories never end. Even today, Ito continues to sit at his drawing table, taking on new projects about old memories.

One Comment