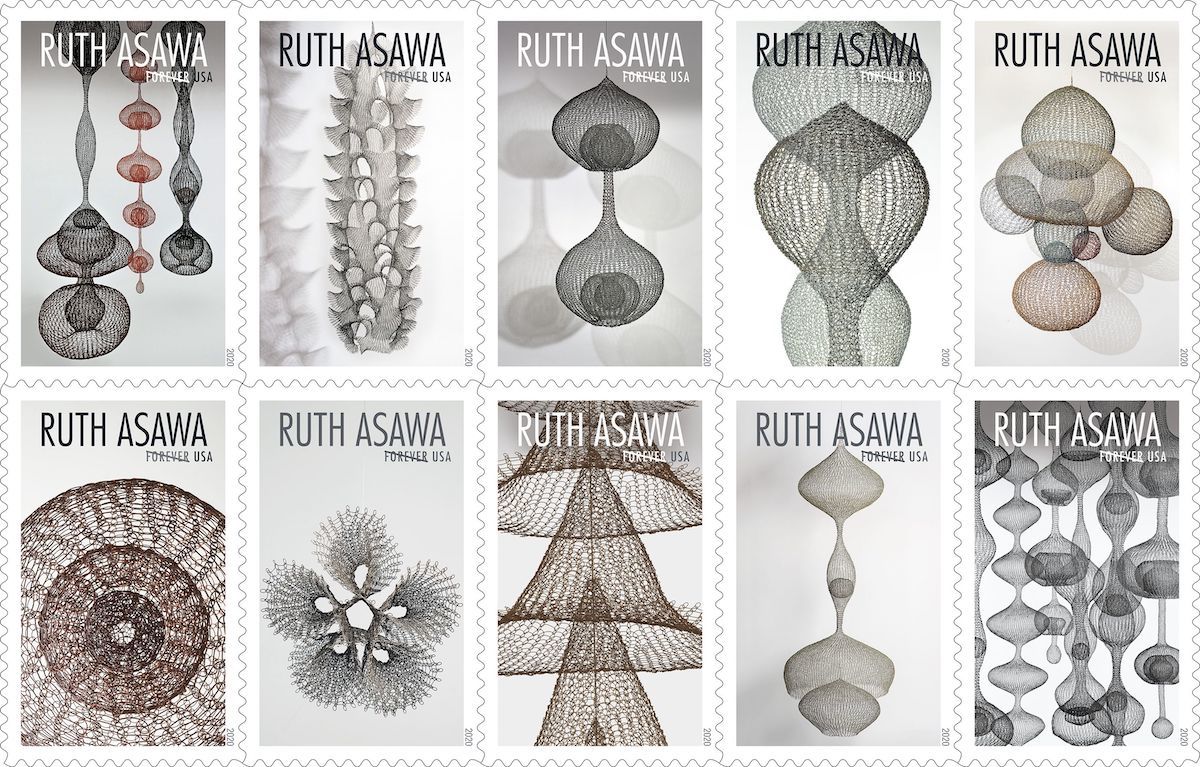

Stamps commemorating the works of artist Ruth Asawa. (Photo: U.S. Postal Service)

The late-Ruth Asawa’s legacy as an artist and arts education advocate is revisited as her works are a testament to the importance of art benefitting the greater good.

By Rob Buscher, Contributor

It is not uncommon for an artist to be posthumously recognized for his/her genius, but the amount of attention that the late-Nisei artist Ruth Asawa is currently attracting is unprecedented for a member of the Japanese American community.

Ruth Asawa drawing while interned in Rohwer, Ark., 1943 (Photo: Courtesy of the Ruth Asawa estate)

In April, author Marilyn Chase published a high-profile biography of the artist. In July, the New York Times ran a detailed feature about Asawa’s life as her works re-emerge as high-ticket items in the art auction market. Then in August, the U.S. Postal Service issued commemorative stamps featuring Asawa’s woven wire sculptures. Asawa was also a major subject in the 2020 Emmy Award-winning PBS documentary “Masters of Modern Design,” which focused on Nisei artists whose works helped define the cultural landscape of postwar America.

Asawa is truly having a moment, which is why it seems appropriate to revisit her legacy as an artist and arts education advocate who also happened to be Japanese American.

Asawa is perhaps best remembered for her looped wire sculptures, but her legacy in the San Francisco Bay Area (where she spent six decades of her life) runs far deeper with her numerous public sculptures and decades of arts education advocacy. Although much of her work is not directly attributed to her identity as a Japanese American, neither can it be completely divorced from the events that shaped her adolescence.

Ruth Asawa, Albert Lanier and daughter Aiko in front of a tomato sign they designed and painted for Asawa’s parents’ farm in Anaheim, Calif., 1949. (Photo: Courtesy the Ruth Asawa estate)

Growing up in the Greater Los Angeles area, Asawa spent most of her time out of school working on the 80-acre farm that her Issei parents leased in Norwalk, Calif. Like all Japanese Americans, her life would change forever in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor.

In a 1990 interview with the Noe Valley Voice, Asawa explained, “In February of 1942, on a Sunday morning at about 11 o’clock, two FBI men came, flashed their badges and said to my father, ‘We’re here to pick you up, Mr. Asawa.’ He was in the field when they came. They gave him enough time to have lunch. I remember that day vividly. My sister, Chiyo, had made a lemon meringue pie. So, he ate lunch, had a piece of pie. I ironed a white shirt. He got into the one suit he had, and then they took him. And we never saw him from 1942 until 1946.”

The family had no news of Mr. Asawa’s whereabouts until a year later, when they learned he was being held in an Alien Detention Center in Lordsburg, N.M., a facility where several Issei were killed by prison guards. Adding to the climate of uncertainty, Asawa’s younger sister, Kimiko, was stranded in Japan, where she would spend the duration of World War II.

Asawa was left with her mother and siblings to figure out what to do with their possessions, and after the evacuation notice was issued, she stopped attending school in April 1942 to help sell off the family’s farm equipment.

Asawa wrote, “I was 16, we were just packing up and trying to dispose of our tractors, our horses, our farm equipment, our trucks, our car. And we were being evacuated from the life my father had worked on since 1902, when he began farming in California. … I think it’s humorous for anybody to think that the $20,000 that we may receive through the Redress can ever compensate for the loss. As modest as our farm was, we lost two tractors, we lost two trucks, four horses, all the farm equipment. We lost everything. We didn’t have household goods of any value, but what allowed my family to make a living was totally gone.”

Like many of the Nisei who experienced incarceration during their adolescent years, Asawa’s experiences would have profound and lasting impacts on the course of her life.

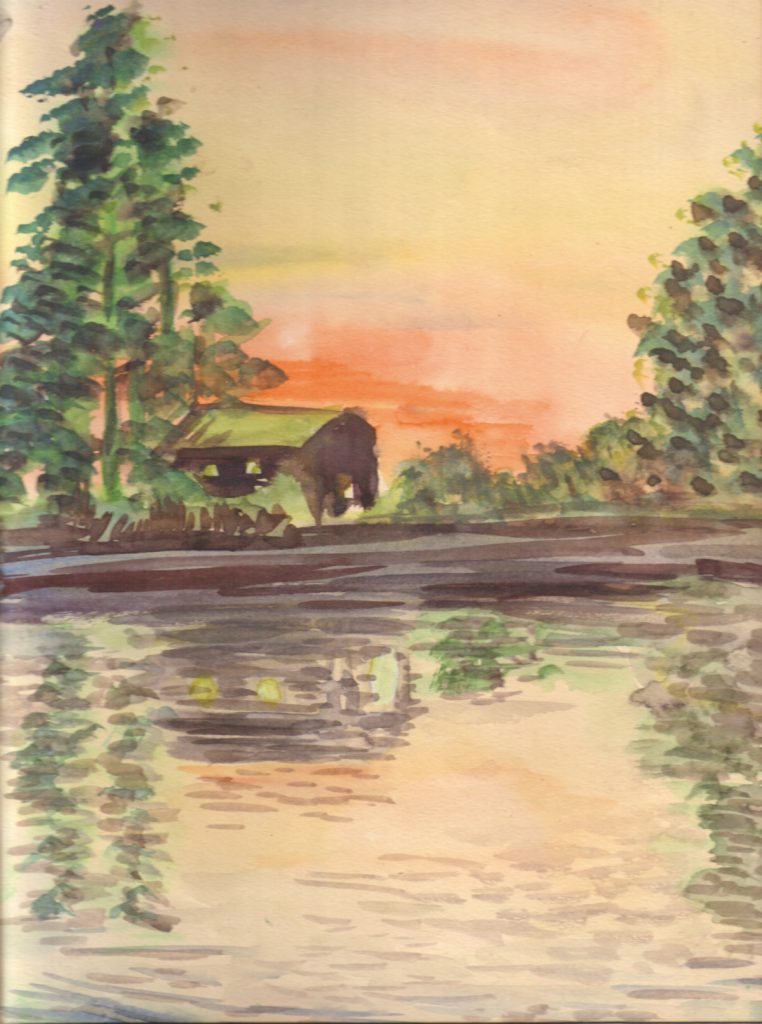

It was during her time at the Santa Anita assembly center that she took her first drawing course, taught by Disney animator Tom Okamoto. While in Arkansas at Rohwer, where her family was sent afterward, Asawa would have the opportunity to work on her first artist commission — illustrating the camp yearbook. Although she would go on to study education, because of wartime anti-Japanese racism, she was unable to complete the student teaching requirement of her degree. If not for those experiences, Asawa might never have become an artist.

On the Bayou (WC.309), 1943 watercolor on paper (Photo: Artwork © 2020 Courtesy of the Ruth Asawa estate)

Asawa’s daughter, Addie Lanier, shared the following reflection about her mother’s wartime incarceration: “Her internment experience was in some ways a mixed blessing. She was 16 when she went to Santa Anita, and 17 when she left for Milwaukee State Teacher’s college. Her identity as an independent teenager coincided with the internment, which took away all parental oversight and authority. … From the time she was 17-1/2 until she was 22, she had almost no interaction with her parents. Little to no financial support from her family. She was on her own.

“The racism she experienced was profound, but she also had people (like her English teacher in the camp, or friends she met in college or the mother in one of the families she au paired for) that told her that she was valuable and talented, and that her government had mistreated her,” Lanier continued. “The world that opened up to her was diverse and such a contrast to her family farm. For example, she was taken to German Bund meetings in Milwaukee by a friend, she traveled to Mexico twice on the Greyhound bus, she became lifelong friends with European artists fleeing the Nazis and she got to experience Black Mountain College in North Carolina. None of this would have happened if she had not been interned, and her time at Black Mountain College changed the trajectory of her life.”

Black Mountain College would prove to be a transformative experience that not only impacted Asawa’s career, but also allowed her to meet her future husband, Albert Lanier. Initially, Asawa planned on attending only a single six-week summer term, but she instead ended up spending three years there.

There, she was mentored by Josef Albers, a Bauhaus artist who fled Adolf Hitler’s Germany, and Buckminster Fuller, a polymath inventor and architect who reinvented himself after the Great Depression ruined his business. Both men had lost everything and rebuilt their lives — familiar perhaps to what Asawa was experiencing in her own life at that moment.

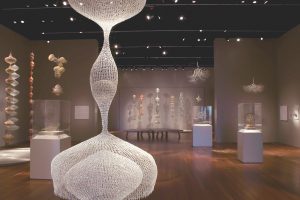

Installation view of Contours in the Air at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, Calif., 2006 (Photo: Laurence Cuneo © Ruth Asawa Estate)

During the summer of 1947, Asawa would have another fateful encounter that would shape her work for many decades to come when she met a Mexican craftsman who taught her how to weave baskets. This technique would be the foundation of her signature looped wire sculptures that Asawa described as “like drawing in space.”

Asawa expanded on that point in a quote from her estate’s website: “My curiosity was aroused by the idea of giving structural form to the images in my drawings. These forms come from observing plants, the spiral shell of a snail, seeing light through insect wings, watching spiders repair their webs in the early morning and seeing the sun through the droplets of water suspended from the tips of pine needles while watering my garden.”

Whether she acknowledged it at the time or not, there was greater significance in Asawa’s use of wire — a symbol of confinement, which she transformed into objects of beauty.

The following year in 1948, Asawa and Lanier decided to get married after graduation. This was no easy feat at a time when anti-miscegenation laws prevented them from being legally wed in most places in the country.

Acknowledging the possible challenges ahead, they sought the advice of their faculty mentors. Asawa recalled, “Albers thought I would make a good mother. I told him I wanted about six children. He said, ‘Gooooood, gooooood.’ And he told Albert, ‘Don’t ever let her stop her work.’ It was very good advice, and Albert has always been very supportive. Then, Bucky told us, ‘The world is your oyster.’ And that’s all he said. I didn’t know what that meant at the time. But what he seemed to be saying was that each of us could shape our own world. You become the pearl, and you rub and you rub. And you make a big pearl out of your life.”

Letters that Asawa wrote to Lanier suggest that her family was generally supportive of their union, but they wanted her to wait until the family farm recovered financially from the wartime incarceration.

Ruth Asawa at the drawing board.

An excerpt from a letter dated Nov. 15, 1948, reads, “Mama said think carefully, then decide. Wants me to work for a year to justify my studying. The real reason is that they are extremely exhausted, and very little left of their physical energy. Lois finally wrote, too, and wants me to help financially mama and papa, to get George back to school. I am all willing. She is all for our plans, but not so soon . …” Another letter from December that year summarized her family’s attitude to the marriage succinctly as, “They dare to be tolerant, for we have all suffered intolerance innocently.”

Moving to San Francisco in 1949, Asawa and Lanier would go on to raise six children while working as a self-employed artist and architect. Asawa experienced some early success in the mid-1950s exhibiting at Manhattan’s high-profile Peridot Gallery, whose clientele included Nelson Rockefeller.

Still, the couple struggled to make a decent living through project-based work. Despite these challenges, Asawa actually turned down an offer from a design firm who wanted to hire her and provide her with childcare. Instead, she chose to work from her home studio, integrating her workspace and family life.

Reflecting on the nontraditional pathway that she took in her career as an artist, Asawa wrote, “The important thing is how you balance the two — your work and raising children. Because I had the children, I chose to have my studio in my home. I wanted them to understand my work and learn how to work. If I hadn’t spent all those years staying home with my kids and experimenting with materials that children could use, I would never have done the Ghirardelli and Hyatt fountains.” Indeed, two of Asawa’s best-known installation sculptures were inspired by techniques she experimented with during this time period.

Unfortunately, at a time when misogynistic attitudes dominated the art world, the same strengths that she saw in this home studio approach were panned by critics, who dismissed her as a “housewife,” as she was disparagingly referred to in an article titled “Eastern Yeast” that ran in the Jan. 10, 1955, issue of Time Magazine. Meanwhile, her contemporary, Isamu Noguchi, was being hailed as a leading U.S. sculptor. Undeterred, Asawa continued working out of her home studio and quietly succeeded like many Japanese Americans of her generation did in the postwar era.

Ruth Asawa with friends during her exhibition at the Peridot Gallery in New York, N.Y., 1954 (Photo: Courtesy of the Ruth Asawa estate)

Asawa’s career took an unexpected turn when she became politically engaged as an advocate for arts education in the public schools. Concerned at the lack of quality arts education that existed in her children’s schools, Asawa co-founded the Alvarado School Arts Workshop in 1968.

The innovative program integrated professional teaching artists into classrooms in more than 50 San Francisco public schools. Shortly after, Asawa would become a member of the San Francisco Arts Commission, where she lobbied politicians and charitable foundations to support public arts programs. Later, she would also serve on the California Arts Council, the National Endowment for the Arts and become a trustee of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Asawa’s work as an arts educator and advocate aligned with the concepts she explored through the public art installations she became known for in her later career. Namely because art appreciation plays an important role in arts education, and what better way of making art accessible to everyone than by creating it in a public space. These aspects of Asawa’s work are widely acknowledged, but to what extent did her heritage influence her works in this later period?

Since her arrival at Black Mountain College in 1945, Asawa’s identity had become primarily associated with her artistic pursuits. However, it was not uncommon for critics to misinterpret her wire sculpture works as being rooted in her Japanese heritage. Whether or not this led to an intentional distancing from her culture, it appears that Asawa identified foremost as an artist.

Addie Lanier provided her perspective on their family’s relationship to Japanese culture: “Our first identity was always to the arts community. When I think of my childhood, I think of my parents’ friends, who were always artists, architects, draftsmen, gardeners and their kids. She always made a Japanese New Year celebration with sushi and chicken teriyaki. My older sister and brother learned how to eat natto, took calligraphy classes, and my older sister studied shamisen. But by the time I came along, we didn’t have much interaction with San Francisco’s Japantown. Other than going to Soko Hardware (my father always got Christmas stocking stuffers from Soko), or the grocery Uoki Sakai on Post Street or very occasionally to the movie theater that showed samurai movies, we didn’t go there often.”

Four sculptures from Asawa’s later career suggest an evolving relationship with her Japanese American identity.

The first is Asawa’s 1976 “Origami Fountains” – located in the middle of San Francisco Japantown next to Soko Hardware. Consisting of cast bronze fountains in the shape of large origami flowers, Asawa designed the entire plaza including the cobblestone and concrete bas-relief panels on the benches. Set in the center of Japantown’s historic business district, this installation is a veritable love letter to her Japanese American community.

The use of traditional Japanese motifs and folk arts in this installation indicates that perhaps Asawa longed for her Japanese American culture after spending three decades in predominantly non-JA spaces.

Aurora Fountain, polished stainless steel, Bayside Plaza, San Francisco(Photo: Hudson Cuneo © Ruth Asawa estate)

A decade later in 1986, Asawa would revisit the origami technique in her “Aurora Fountain,” located in Bayside Plaza at the Embarcadero. Addie Lanier offered the following context for this piece: “She enjoyed collaborating with the building’s architect, my father, Albert Lanier, who as an architect often helped her with technical drawings for the larger commissions, and her dear friend Mai Kitazawa Arbegast, who was the landscape architect for Bayside Plaza. The origami pattern, when made in paper, is a circular crown that rotates completely on itself. It’s a great toy for children. She was always interested in the material, finding new uses for a material that was almost taken for granted. She has taken the flexibility of this origami pattern and turned it into stainless steel.”

In addition to replicating the origami shape technique from her Japantown fountain, this sculpture integrates Asawa’s love of child arts education as she continued her exploration of Japanese American identity.

The most literal interpretation of Asawa’s Japanese American experience came in 1994 when she was commissioned to design the “San Jose Japanese American Internment Memorial.” This was a significant departure from her previous works, which are generally abstract. It was also the first time that Asawa would address the wartime incarceration directly through her work.

The memorial consists of a freestanding bronze bas-relief panel located outside of a federal building, showing scenes from her own incarceration experience at Santa Anita and Rohwer alongside other experiences from the broader Japanese American narrative.

Reflecting on her process for this atypical work, Asawa wrote, “I had to dig deep into my past to find the common threads with other Japanese immigrants who endured the struggle and am glad I was part of it.”

Asawa’s final work on this theme was her 2002 “Garden of Remembrance,” a commission for San Francisco State University that she did in collaboration with landscape architects Isao Ogura and Shigeru Namba. The installation was meant to honor the 19 Japanese American students who were forced to withdraw from classes at SFSU in 1942 because of the evacuation orders.

Garden of Remembrance at San Francisco State University (Photo: Aiko Cuneo © Ruth Asawa estate)

The original concept was to incorporate boulders from each of the 10 WRA camps, though that proved too costly. Instead, 10 locally sourced stones symbolize the deprivation of the camps that were located in dry, desert-like places. In contrast, a waterfall runs over them, signifying the return of the incarceration survivors to the coastline after the war.

In a statement released during the dedication of the installation, Asawa wrote, “A lot of students don’t know about the internment camps. They believe that it doesn’t affect them, but I think it’s important that they recognize what took place.

I thought it would be nice if we could do something that told the story but not in a bitter way and not just as a Japanese story.”

Asawa did not speak about these works together as a collection, and each was made for separate commissions. That said, looking at these works together demonstrates an evolution in how Asawa addressed Japanese American subjects over the span of four decades. In many ways, her process echoes how other Nisei processed the trauma of wartime incarceration.

After several decades of assimilation, Asawa reconnects to her cultural roots through the Japantown “Origami Fountains.” Building upon that concept, “Aurora Fountain” normalizes the integration of Japanese culture into a non-Japanese space at the Embarcadero. With her “San Jose Internment Memorial,” Asawa delves into her trauma headfirst and confronts the memories of her past. Finally, with “Garden of Remembrance,” Asawa evokes a reconciliatory attitude, recognizing her Nisei contemporaries and educating future generations.

While the themes identified here might not have been conscious choices by the artist, these clues would suggest that Asawa was able to process her trauma through these works. If this was indeed the case, it appears that she had made peace with her experiences in camp by the late stage of her career as she came to embrace this aspect of her Japanese American identity.

In the last decade of her life, Asawa was honored with a major retrospective of her work at the de Young Museum in 2006. Then in 2010, the public arts high school in San Francisco that she had advocated for decades was renamed the Ruth Asawa San Francisco School of the Arts in her honor.

After a three-decade battle with Lupus, Asawa finally succumbed to her illness in 2013. Yet, Asawa’s spirit of advocacy lives on in the school programs that she helped to build and her many public arts installations.

Several of Asawa’s children are now artists themselves, and Addie Lanier manages her estate, ensuring that the legacy of her mother’s work will live on.

Reflecting on Asawa’s impact on her own family, Lanier said, “I would say that we don’t have a strong connection to the Japanese American community, but I believe there is a Japanese aesthetic, which we have inherited from our mother. My brother, Paul, is a ceramic artist, my other brothers are general contractors, but they work in wood, my sister, Aiko, creates assemblages and collages. I garden. Our mother often said that she wasn’t interested so much in creating artists, but that the arts expanded your abilities no matter what you did with your life. The arts make you stronger, more resilient, more creative and better problem solvers.”

Asawa expressed a similar sentiment regarding the utilitarian nature of art in her writings. She wrote, “I think that the reason the arts are important is because it is the only thing that an individual can do and maintain his individuality. I think that is very important — making your own decisions. If you count everything that we fight for — better schools, better health care, more social awareness — we are letting other people make the decisions for us. We are not taking our lives into our own hands and making those decisions for ourselves.”

As a woman whose adolescence was shaped by a government making decisions on her behalf, Asawa lived the rest of her life on her own terms. She built a successful career as an artist while raising a family of six, and she still managed to advocate for the greater public good. Perhaps Asawa’s life can be best summarized in her own words: “Art saved us.”