Classmates Bill Higuchi and Setsuko Saito sit next to each in the center of the front row in the photograph of their ninth grade class at Heart Mountain High School.

Writing a book about the WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans opened the author’s eyes to her own family’s history.

By Ray Locker, Contributor

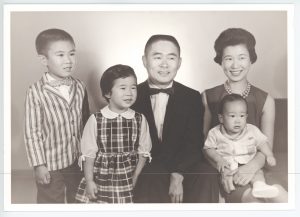

The Higuchi family in 1962. Pictured (from left) are Ken, Shirley, Bill and Setsuko. Bob is sitting on his mother’s lap. (Photo: Courtesy of Shirley Ann Higuchi)

Growing up in Ann Arbor, Mich., in the 1960s and ’70s, Shirley Ann didn’t know any other Japanese Americans outside of her own family. Her connection with the Nikkei community came only through the copies of the Pacific Citizen that arrived at her family’s home.

Somewhere in her family’s history, she knew, was a place called Heart Mountain, the site in northwestern Wyoming where her parents had met as children in seventh grade. If her parents referred to Heart Mountain at all, they only called it “camp.”

“I think I had a very isolated and narrow view of the Japanese American incarceration because there wasn’t a lot of information given to me on that topic,” Higuchi said. “My parents never said much about that experience, except sometimes my mother would say that was where she met my father when they were children. She made it seem like camp wasn’t that bad and kind of a fun place to be.”

Setsuko Saito at the docks in San Francisco before she sailed for Tokyo for an arranged marriage that she rejected. Pictured (from left) are Yoshio, Hiroshi, Setsuko and Kathy Saito.

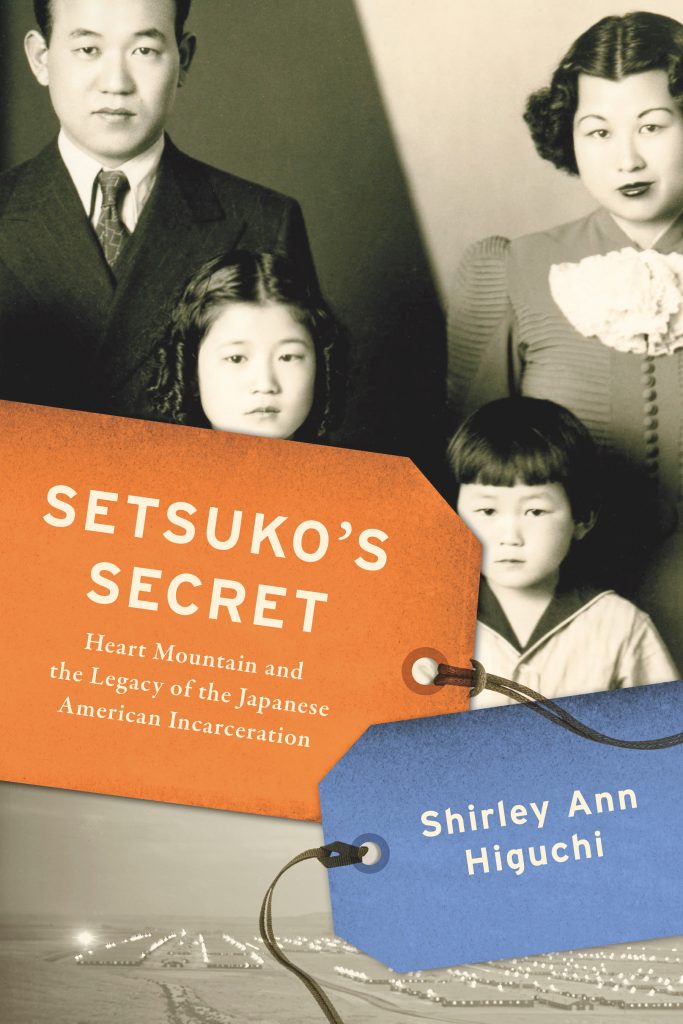

Higuchi now has told the history of both her family and the incarceration in her new book, “Setsuko’s Secret: Heart Mountain and the Legacy of the Japanese American Incarceration.” The book, set to be released Sept. 15 by the University of Wisconsin Press, is a memoir and history of the Japanese American experience from the arrival of the first wave of Japanese immigrants through the incarceration to the present.

The book is rooted in Higuchi’s discovery in 2005, at her mother’s deathbed, that Setsuko Saito Higuchi wanted her traditional condolence gift donated to the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation. She had anonymously donated a substantial sum of money to the foundation’s effort to build a museum on the site where almost 14,000 people spent the war years living behind barbed wire.

Shortly after her mother’s death, Higuchi was invited by Heart Mountain officials to join them at a dedication of a walking tour at the camp site in her mother’s name. They then invited her to join the foundation board, and she became the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation board chair three years later.

◊◊◊

The ‘Sansei Effect’

Through the last dozen years leading the foundation, Higuchi learned that her experience resembled that of other Sansei. Their Nisei parents often kept the details of the Japanese American incarceration from them, leaving the children to navigate the consequences of that ordeal on their own.

“Setsuko’s Secret: Heart Mountain and the Legacy of the Japanese American Incarceration.” (click photo to purchase)

Higuchi calls this the “Sansei Effect,” the sense among third-generation Japanese Americans that they will never live up to the expectations and experiences of their parents while often understanding little about what these parents withstood.

“We did not know what the incarceration had done to my parents’ generation and how it created the various rules — spoken and unspoken,” Higuchi wrote in “Setsuko’s Secret.” “For my older brother, Ken, that confusion manifested itself in sporadic outbursts of anger — he once flipped over a six-person round table in the family room for reasons I cannot recall — and a manic desire to live up to the expectations he believed our parents had for him.”

Ken Higuchi, who became an engineer working for a defense contractor, died in a 1986 car accident. Shirley Higuchi believes his death was connected to the stress he placed on himself as a Sansei.

“Many Sansei feel lost, in part because they do not understand the events that shaped their parents and grandparents and that directed their behavior,” she wrote. “They do not know why their parents were obsessed with propriety, worked all of the time or carried an unspoken shame.”

Finding a better understanding of the multigenerational mental health trauma experienced by many Japanese Americans has led Higuchi to become more active in the series of healing circles led by Dr. Satsuki Ina, a psychologist who was born while her parents were incarcerated in the Tule Lake, Calif., camp.

◊◊◊

A Richer History

Higuchi also discovered more details about the lives of many of the people with whom she works at Heart Mountain, including Takashi Hoshizaki, one of the 85 men from Heart Mountain who resisted the military draft in 1944 and were sent to federal prison.

The story of the draft resisters was long obscured by community leaders who emphasized the valor of the Nisei soldiers who served in Europe and Asia with the 100th Infantry Battalion, 442nd Regimental Combat Team, 522nd Field Artillery Battalion and the Military Intelligence Service.

Hoshizaki, who is now a Heart Mountain board member, was 18 when he resisted the draft. After his release from prison in 1946, he earned a Ph.D. in botany and spent decades working on research for the space program.

“His career after the war included service in the Army and conducting research as a botanist in Antarctica,” Higuchi said. “I realized he was more than just someone who promoted civil rights and stood up for his own rights at Heart Mountain.”

She also learned more about the relationship of former Wyoming Sen. Alan Simpson and his family with Heart Mountain. Simpson’s father, Milward, was a World War I veteran who led the Cody, Wyo., American Legion post. Not long after the Heart Mountain camp opened, Milward Simpson visited Heart Mountain to welcome the legionnaires among the new incarcerees.

One was Clarence Uno, the father of Raymond Uno, who would later become the national Japanese American Citizens League president and the first minority judge in Utah.

“Milward Simpson also encouraged his sons, Pete and Al, to visit the Japanese American incarcerees at Heart Mountain, which led to the meeting of Al and Norman Mineta, which is well known and discussed in my book,” Higuchi said.

Alan Simpson met Mineta, who would later become a U.S. representative from California and a two-time Cabinet member, during a Boy Scout jamboree at Heart Mountain. Their 77-year friendship is one of the most cherished parts of Heart Mountain history.

◊◊◊

Relevance for Today

Higuchi said “Setsuko’s Secret” is relevant to today’s political climate in which the current administration is promoting border and immigration policies similar to those that plagued Japanese Americans before, during and after WWII.

Shirley Higuchi (center) leads the Pledge of Allegiance on Aug. 20, 2011, the grand opening of the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center. To her right are Sen. Daniel Inouye, Secretary Norman Mineta and Sen. Alan Simpson. (Photo: Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation)

She recounted the story of what happened in the days following the 9/11 attacks, when Mineta was the Secretary of Transportation for Republican President George W. Bush.

“I think the book is a reminder of what the government, politicians and the media should not do during a wartime crisis or other dramatic moments that can occur in our nation’s history, like Sept. 11,” Higuchi said. “When President George W. Bush stood up with then-Secretary Norman Mineta and said, ‘We do not want to do to Muslim Americans what we did to Norm in 1942.’ That shows that at the greatest levels of our nation’s leadership, we can get support for other groups in times of crisis.”

Higuchi has used her research for “Setsuko’s Secret” as material for a series of columns she has written for media outlets that includes the Seattle Times and the Salt Lake Tribune. She has seen multiple parallels between the incarceration and current policies involving private prisons and immigrant detention centers, family separations and the Muslim ban.

◊◊◊

A Final Discovery

It wasn’t until the end of the writing of the book that Higuchi realized more hidden elements of her family’s history.

Last November, she traveled to Japan as part of the Japanese Foreign Ministry’s Up Close program to speak to students and government officials about the incarceration. Part of the program involved going to Saga Prefecture on the island of Kyushu to visit family members from where her father’s family had emigrated to the United States.

There, she met her cousin, Sumiko Aikawa, who recounted the time in 1957 when Higuchi’s grandmother, Chiye Higuchi, spent a night with Aikawa, her niece, and told her about the suffering the family endured during the incarceration.

Until then, Higuchi said she never knew how her grandmother viewed the incarceration.

“I had spent my entire life believing that Grandmother Chiye was a rock, someone composed who had few needs,” Higuchi wrote. “She never expressed much emotion other than the love I felt emanating from her during my childhood. Like all of my relatives, I thought the incarceration experience for her, as well as for the rest of Japanese Americans, was just a blip on the screen. I never realized the extent of my grandmother’s anguish during the war and the years afterward.”

JACL DC is hosting a book event on Oct. 7. Check the chapter’s website for details (https://jacl-dc.org/). If you preorder a book from Politics and Prose in Washington, D.C., write “JACL DC book event bookplate” in the message to the bookseller in the order form, and you’ll get an author-signed bookplate in your book (until they run out)! Visit https://www.politics-prose.com/book/9780299327804. For more information, visit the “Setsuko’s Secret” Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/SetsukosSecret/.

“” is also available for advance purchase at Amazon. It is also available at your local independent bookseller at https://www.indiebound.org/indie-bookstore-finder.