Karen Korematsu, in red, with members of the Philadelphia JACL Chapter, is presented with a City Council Resolution. (Photo: Courtesy of Philadelphia JACL)

The program focuses on highlighting ways in which Japanese Americans can practice allyship with other communities of color; other highlights include a City Council Resolution presented to Karen Korematsu.

By Rob Buscher, Contributor

JACL Philadelphia hosted its annual Day of Remembrance on Feb. 22 at Philadelphia City Hall at a time when Japanese American communities across the country were coming together. The events of last month seem distant in the wake of the growing COVID-19 pandemic that is sweeping our nation, and it is difficult to accept this may be the last time for a long while that we will experience community in such great numbers.

Yet, as we adjust to the new normal of social distancing and making sacrifices now so that our communities can thrive in the future, it is worth pausing to reflect on the many important conversations that were held at that time.

The focus of Philadelphia’s DOR program was to highlight the ways in which Japanese Americans can practice allyship with other communities of color and marginalized groups in our society.

In particular, we sought to highlight two of the major issues our local community is actively advocating around — ending immigrant detention and combatting Islamophobia.

JACL Philadelphia was joined by Karen Korematsu, executive director of the Fred T. Korematsu Institute, who anchored a panel discussion that examined the ways in which the legacy of Japanese American incarceration can be leveraged for contemporary advocacy purposes.

Council on American-Islamic Relations Outreach Director Ahmet Selim Tekelioglu gives remarks. (Photo: Hiro Nishikawa)

Korematsu was joined by Ahmet Selim Tekelioglu, outreach and education director at the Council on American Islamic Relations Philadelphia, and Troy Turner, a member of the Sunrise Berks Movement, who represented the Shut Down Berks Coalition.

Both organizations have longstanding partnerships with JACL Philadelphia, whose members have been involved in coalition-building with the Muslim

Panelist Troy Turner from Sunrise Berks represented the Shut Down Berks Coalition. (Photo: Hiro Nishikawa)

American community since 9/11 and active participants in the Shut Down Berks movement that aims to close the federal detention center in Berks County, located about an hour and a half northwest of Philadelphia.

Similarly, the Korematsu Institute under Karen Korematsu’s leadership has been highly engaged in national partnerships with CAIR representatives and is taking an increasing role in conversations about immigrant detention.

The many shared experiences between their respective communities such as intergenerational trauma and use of storytelling in advocacy resonated amongst the panelists, making for a rich discussion about the local and national implications of continuing to strengthen such partnerships.

Following the panel, JACL Philadelphia members engaged in a lively Q&A session with panel participants, addressing issues ranging from strategies for collective advocacy to implications of organizing cross-community voting blocs.

Another highlight of the event was the presentation of a special resolution from the Philadelphia City Council commemorating Korematsu Day, sponsored by Councilmember Helen Gym, which was read aloud by several of the chapter’s incarceration camp survivors.

This was the second event that JACL hosted at City Hall in the month of February, which coincided with the second phase of the “American Peril” exhibit on the history of anti-Asian racial propaganda. The exhibit opened on Feb. 7 with a public reception and is scheduled to run through the end of March (though city hall is now closed due to the COVID-19 outbreak).

The original exhibit first debuted at the 2018 Philadelphia Asian American Film Festival and emerged from a research project that my wife, Cathy Matos, and I have been working on since 2017, when we began collecting anti-Asian racial propaganda as classroom teaching resources.

The 2018 exhibit featured a collection of more than 60 original printed materials and other artifacts that span nearly 150 years, from the Chinese Exclusion Era and World War II anti-Japanese Propaganda to post-9/11 Islamophobia.

While much of the original intent of the exhibit remains the same in its approach to educating contemporary audiences about the long and interconnected history of xenophobic bigotry that subsequent generations of Asian immigrants and their descendants have faced in this country, the 2020 exhibit is all about connecting these ideas to the present.

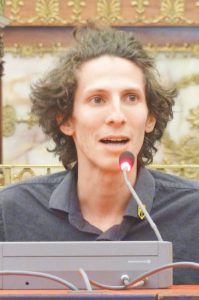

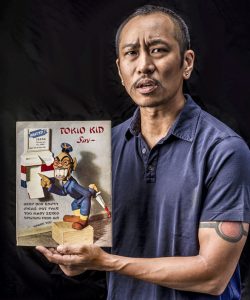

Makoto Hirano, as seen in “American Peril: Faces of the Enemy.” (Photo: © Justin L. Chiu)

The second phase of the “American Peril” exhibit, titled “Faces of the Enemy,” has been expanded to include a series of portrait photographs produced by PAAFF Programmer Sunny Huang and shot by Philadelphia-based photographer Justin Chiu.

Chiu’s series juxtaposes individuals who have been targets of racial propaganda with exhibit artifacts to highlight the impact of propaganda on members of the Philadelphia community.

These portrait photographs show the human impact of such propaganda so that younger generations can better appreciate the ongoing and harmful nature of racial propaganda by connecting it to the lived experiences of others.

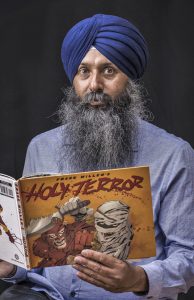

In light of the anti-Islamic rhetoric that certain conservative elements have brought into mainstream political discourse, it seemed necessary to use our photo series to draw attention to the clear parallels between the Japanese American incarceration experience and scapegoating of the Muslim American community in the aftermath of 9/11 and in recent years.

More importantly, these photos show a clear example of how propaganda techniques from the 1940s are currently being used to defame and dehumanize the Muslim American community, which puts an already vulnerable community at further risk of racialized violence.

Karnail Singh as seen in “American Peril: Faces of the Enemy.” (Photo: © Justin L. Chiu)

The artifacts featured in this second phase of the exhibit were also expanded to include a more robust collection of anti-Muslim propaganda, demonstrating how racial caricature has played a crucial role in bolstering public support for the decades of U.S. intervention in the Middle East.

Over the past 15 months since the exhibit first debuted, many issues developed within our contemporary political discourse that under previous administrations would have been thought inconceivable.

Although the travel ban on visitors from Muslim-majority countries and other countries deemed dangerous to the U.S. has been in effect since June 2018 when the Supreme Court ruled to uphold it, President Donald Trump just recently expanded the bill to include six additional countries the same week as the Day of Remembrance.

It is unsettling to think what other restrictions might be implemented in the coming months as our country addresses the current public health crisis, which has the potential to affect long-term immigration policy decisions.

President Trump has already begun referring to COVID-19 as “the Chinese virus” in press conferences this week, further stoking racialized fear.

Another issue central to this exhibit is the immigrant detention centers. While this has been an issue since the Obama presidency, media coverage related to the increasing numbers of family separations among immigrants became omnipresent throughout the 2019 news cycle.

From far-right commentary encouraging the use of military force to halt the immigrant caravan to grassroots advocacy campaigns like Tsuru for Solidarity energizing broad-based community support to end family separation — this issue has been front and center for much of the last year.

This phase of the exhibit further delved into contemporary discourse around immigration by pairing the portraits with quotes that were excerpted from interviews we conducted with each photograph subject that sought to contextualize their own experiences related to xenophobic rhetoric.

Among the most powerful was a statement made by Ali K., a second-generation Iranian American who is married to a Japanese immigrant. He is shown in a portrait accompanying his wife and daughter.

Ali’s quote reads, “I’m worried about my biracial Iranian-Japanese daughter. It’s disheartening to see how willing the media is to dehumanize our perceived opponents of the moment and how these same practices go on today. What’s especially concerning is how the actual news media, which we’d want to be more responsible, show such caricatures. Media can be used as propaganda in a very subtle way. It isn’t like Soviet propaganda that’s in your face. This is a lot more insidious and can affect us without us knowing it.”

Sadly, the use of propaganda to drive public sentiment against certain groups of people has been highly evident throughout the course of this exhibit.

As we began installation of the exhibit in mid-January, U.S.-Iran relations were deteriorating into dangerous new levels of brinkmanship that nearly brought our two countries to war with one another.

Now as I type this, we are facing a wave of hate crimes against Chinese and other East Asians who are being scapegoated for the Coronavirus pandemic.

It is our hope that by hosting this exhibit in key locations at City Hall, we can instigate a dialogue at the highest level of Philadelphia politics. The collection is currently on view where our city’s top elected officials conduct their daily business, on the second-floor corridor in front of Mayor Jim Kenney’s office and fourth-floor corridor near City Council Chambers.

Indeed, the exhibit has sparked an important dialogue around xenophobic rhetoric of which the Chinese American community has most recently been subject to with the rise of COVID-19.

Weeks before there were any confirmed cases in Philadelphia, Kenney took his staff out to lunch in Philly Chinatown as a symbol of solidarity with the Chinese American community. One wonders, had the mayor not seen the “American Peril” exhibit every day on his way into his office, whether this would have been top of mind.

“American Peril: Faces of the Enemy” was funded in part by the JACL Legacy Fund and Pennsylvania Council on the Arts Project Stream. The exhibit is hosted at Philadelphia City Hall through the Art in City Hall program that is operated by Philadelphia’s Office of Arts, Culture and the Creative Economy. Visit Art in City Hall’s website at https://creativephl.org/american-peril-phase-2 for more details.