A press kit photo for 1942 movie “Little Tokyo, U.S.A.” (Courtesy of Rob Buscher)

The writer-curator offers insight into JACL Philadelphia’s co-presentation of a new exhibit on the history of anti-Asian racial propaganda.

By Rob Buscher, Contributor

In November, JACL Philadelphia will be co-presenting a special exhibit on the history of anti-Asian racial propaganda during the 2018 Philadelphia Asian American Film Festival titled “American Peril: Imagining the Foreign Threat.”

Sponsored in part by the JACL Legacy Fund, this exhibit and the special events held from Nov. 2-30 at gallery space Twelve Gates Arts are free and open to the public. Featuring more than 60 printed materials and other original artifacts, the collection spans nearly 150 years — from the Chinese Exclusion era to World War II-era anti-Japanese propaganda, and even contemporary anti-Muslim propaganda, which Buscher curated from his personal collection that he shares with his wife, Cathy Matos, and the collection of Dr. Jamal J. Elias.

Following is insight by Buscher on the beginnings of his collection and how what began as antiquing turned into an exhibit that explores the history of anti-Asian racial propaganda.

The idea of positioning such objects in a gallery setting might seem counterintuitive for presenting organizations whose missions involve combatting negative media portrayals of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

However, given the current state of our society, in which xenophobic bigotry and racism have re-emerged within the realm of mainstream political discourse, it is important for us to confront the history of racism head-on.

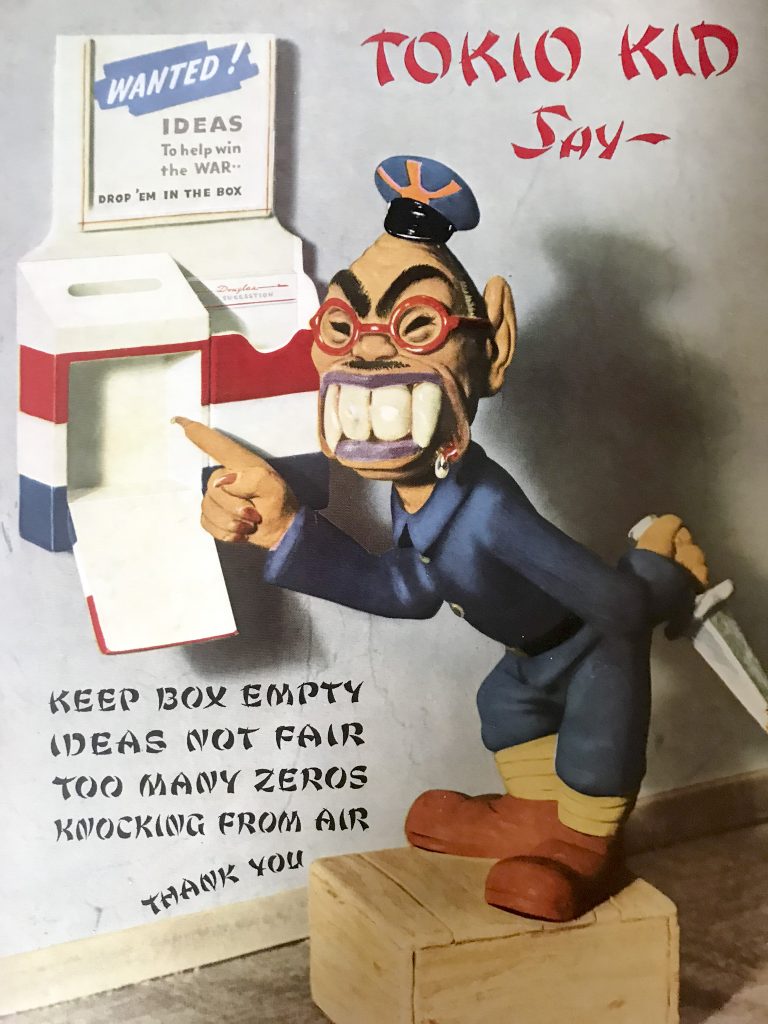

Tokyo Kid,. Douglas Airview magazine, 1943

By studying such hateful artifacts, we can understand how racism continues to be perpetuated in popular media and ultimately develop strategies to disrupt these contemporary racialized propaganda narratives.

Although most people know me professionally as a film programmer and community organizer, I have also been pursuing a parallel career as an academic. Having taught at Arcadia University since 2012, my research focus has gradually evolved from Japanese Cinema Studies (where I started my academic career as a graduate student at University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies) to incorporate more of my own Japanese American perspective.

I recently joined the University of Pennsylvania’s Asian American Studies Program in 2017, where I have been able to expand my research in Asian diasporic cinema and Asian American history. Much of my current research revolves around the politicization of popular cinema and other mainstream media texts in the shaping of public attitudes toward Asian Americans and other ethnic minorities.

Like most institutions, the academy is one that has historically been dominated almost entirely by white Americans, and in many respects, the power structure is still fairly restrictive for scholars of color.

I have found this particularly true in Area Studies (like Japanese Studies) where most of the tenured professors and department heads are not persons of Japanese descent. Not to say this is a prerequisite qualification to being a good professor on the subject, but it does limit their perspective in terms of the connection or lack thereof they have to certain topics.

While the Ethnic Studies movement that occurred on the West Coast opened a fair amount of diversity in many subject matters, it feels like the East Coast (and particularly some of the older institutions) are lagging behind in terms of their support for these crucial fields.

In an earlier March 23, 2018, edition of the Pacific Citizen, I wrote about my experience at the Critical Mixed-Race Studies Conference as a sort of homecoming into the academic space. The work I have engaged in since has benefited from the perspective of critical mixed-race studies that I became familiarized with through that important conference, along with Edward Said’s foundational book on postcolonial studies “Orientalism.” In many ways, the curation of this exhibit is a culmination of my scholarly work to date.

For the purpose of this exhibit, I define “propaganda” as content that 1) promotes one-sided or biased information, 2) reinforces ideology central to systems of control (political, religious, class/race hierarchy) and 3) reduces complex concepts into simple dichotomies.

Newspapers and other periodicals are an obvious source for such content, but we also find propaganda in advertising, popular cinema, lyrical music and even common household objects such as ashtrays or drinking glasses that are imbued with political rhetoric.

As noted by media scholar Narelle Morris in his book “Japan-Bashing,” the impact of popular culture on shaping public opinion has long been overlooked in scholarship. However, the evidence overwhelmingly suggests this to be a major contributing factor with regards to mainstream American perceptions of Asian immigrant communities over the course of the last 150 years.

Purchased largely at our own expense, this collection of racial propaganda began with the impromptu discovery of a WWII-era work poster that my wife and I came across in an antique fair at Philadelphia’s Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts.

Finding a 1940s artifact amidst the many other items of historical note was too rare an opportunity to pass up, and at the time, we thought it would be unlikely to stumble across another such find.

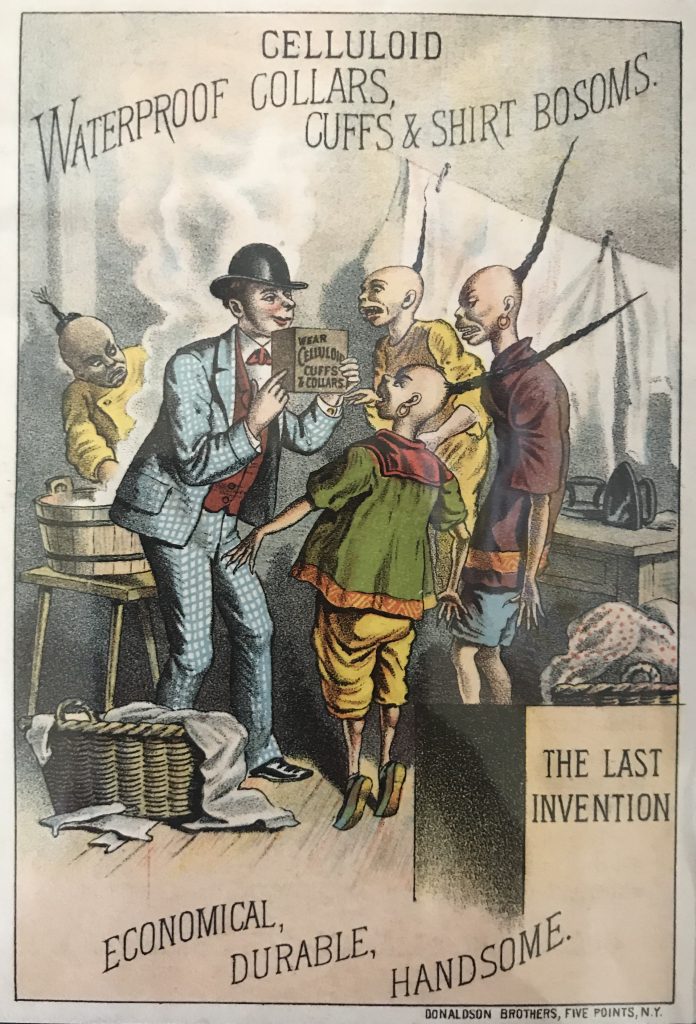

Celluloid Cuffs and Collars the Last Invention trade card, 1880s.

We would soon realize this was anything but the case as we discovered the large volume of anti-Japanese and other anti-Asian propaganda in the resale market during the past year and a half we spent scouring antique markets and online auction sites for the items now in our collection.

It has been particularly interesting to engage with the sellers of these artifacts, whose understanding of the racism implicit in them varies from somewhat apologetic to outwardly prideful, particularly amongst the sellers of 1970s-’90s Japan-bashing materials.

The first such interaction I had was with a seller on Etsy, who had listed their homemade T-shirt protesting Japanese auto imports as “Americana Folk Art.” Another merchant on Ebay who sold me a “No Jap Cars” pin-back button wrote on the exterior of the mailing envelope the Trump-ist phrase, “Buy American, Hire American” — suggesting that at least for some people, this propaganda may still be shaping their worldview.

On the other hand, several of the merchants we met expressed regret at the harmful rhetoric in various printed materials. The woman who sold us our first anti-Japanese work poster at the Kimmel told us outright that she felt bad about displaying the object in public, which is why it was hidden below sightline on the ground next to her display table. She was also more than happy to extend a hefty discount when she learned that I would be using it as an in-class teaching resource for my students.

This was the first spark that ignited our passion for collecting these objects, followed shortly after by an antiquing trip to the self-proclaimed “Antiques Capital USA,” otherwise known as Adamstown, Penn., located just outside of Lancaster.

While we have always enjoyed antiquing, the hunt for anti-Asian racist paraphernalia gave us a specific goal, one that we were less surprised to accomplish with each find. Of particular note during that trip were two issues from the prominent 1890s political satire publication Judge magazine.

The first featured a highly racialized caricature of Hawaiian Queen Liliuokalani being hoisted by the U.S. Navy on her throne of “scandalous government” and “corruption.” The other was an infantilized cartoon portrayal of Philippines President Emilio Aguinaldo being crushed by a U.S. cavalryman’s fist in an issue that ran contemporarily to the Philippine-American War.

It was no accident that both cartoons associated their subjects with blackness and indigeneity to justify U.S. territorial acquisitions in Hawaii and the Philippines, given the institutional racism prevalent throughout the U.S. at that time — less than 30 years after slavery was abolished and amidst on-going land wars with Native Americans.

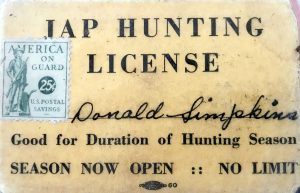

Jap Hunting License

After I began using these first lucky finds as in-class resources and saw how much they resonated with my students, Cathy and I continued our search online for other artifacts relevant to the history of anti-Asian racism.

It wasn’t until early 2018 that Cathy had the inspired suggestion of curating these artifacts into a public exhibit. Twelve Gates Arts (12G) seemed like an obvious location to host it, given the fact that we had previously collaborated in 2016 on an exhibit titled “I Bear Witness.”

Curated by 12G Co-Founder Atif F. Sheikh, the former exhibit combined the works of Japanese American documentary filmmaker Matthew Hashiguchi with new original works by seven Muslim American artists in a single show. A project that was also supported by JACL’s Legacy Fund, Sheikh described the former as “a curated show of works from mainly Muslim American artists responding to the wave of anti-Muslim bias being promoted by the current government administration in the backdrop of historical anti-Japanese racism following WWII.”

Sheikh discussed his organization’s motivation for hosting the upcoming “American Peril” exhibit in an excerpt from 12G’s gallery statement about the show.

“Art is usually associated with freedom and subversion,” he said. “Its power has often been instrumental toward change and revolutions, and it has been used as a medium to reach the masses and raise awareness. At the same time, art has also been appropriated for the purpose of propaganda, used as a form of persuasion to influence the emotions and opinions of a target audience for ideological or political purposes. Although some art historians have resisted the idea of propaganda as art, the power propaganda holds on people’s psyche is undeniable, and that power hold is achieved through the basic human response to art. Wars have been won in people’s minds through the arts.”

Muslim free zone sign

Elaborating on the specific subject of anti-Asian propaganda that is displayed in the “American Peril” exhibit, Sheikh continued, “Propaganda art preaching hate against a perceived foreign threat has always contributed to the creation of an imagined enemy, nurturing a culture of contempt and intolerance. The target may change, but the practice continues to this day.”

Nevertheless, this exhibit will not be for all people. People may question our judgment in showcasing these artifacts in a gallery setting, but I believe it is for the greater good.

In this era of fake news and alternative facts, I would like to think that a primary source artifact is perhaps one text that no one can argue with. However, investing in a collection such as this does raise certain ethical questions that must be contended with. I must admit feeling guilty at times, knowing that we have contributed to the resale economy of objects that have brought great pain and sorrow to our Asian American communities.

A colleague of mine whose research involves collecting postcards and photographs depicting the lynching of African-Americans discussed this issue at length. While I personally draw the line at paying money for an image of a dead body or other active violence being perpetrated, he raised a valid point that there are many who would seek to purchase these vile images for reasons beyond scholarly research. Ultimately, we agreed that it is better for these objects to be in the hands of educators and activists where they can be studied and/or exhibited for public benefit rather than hidden away as a trophy on someone’s mantel.

At the 2018 JACL National Convention, a subset of these anti-Japanese artifacts was showcased in the exhibit room, where they sparked much critical dialogue around the role of propaganda today.

I have every confidence that the full collection will prove even more effective in starting conversations around popular media’s role in shaping our society’s perceptions of immigrants and other historically marginalized groups.

I would like to highlight a few of the special events taking place during the monthlong run of this exhibit. On Nov. 2 from 5:30-8:30 p.m., we will host the exhibit’s opening reception, which will be the first time the collection in its entirety will be shown to the public. On Nov. 9 from 4:30-5 p.m., myself and Cathy Matos will give a brief talk about the process of collecting these artifacts and expand upon some of the ethical concerns explored earlier in this article, followed by a guided tour of the exhibit.

The main exhibit event is a program titled “Propaganda Film Night,” which will take place on Nov. 14 from 6:30-8:30 p.m. This event will include the screening of clips from a dozen or so WWII-era propaganda films and one short documentary produced during U.S. territorial rule by Interior Minister of the Philippines Dean Conant Worcester. The former will be introduced by myself, and the latter by Penn Museum Film Archivist Kate Pourshariati, followed by a guided viewing to help contextualize their historical significance.

Works by both Hollywood and independent filmmakers shown here will demonstrate how motion pictures have been used to shape the opinions of the American public during times of war and subsequent occupation of conquered territories. Like the printed materials in the exhibit collection, this content is offensive in its portrayal of Asian subjects but important for understanding the causes of anti-Asian sentiment in previous generations of Americans. Additionally, this program will illustrate the central role that cinema plays in the way that Americans understand and consume conflict.

We must be ever vigilant over the use and abuse of media to convey propagandist messages. This exhibit is one small step toward educating the public on how to tell the difference between fake news and genuine fact.

“American Peril: Imagining the Foreign Threat” was funded in part by the Japanese American Citizens League Legacy Fund and Pennsylvania Council on the Arts Project Stream.

‘AMERICAN PERIL’ EXHIBIT INFORMATION

Runs Nov. 2-30 at Twelve Gates Arts, located at 106 N. 2nd St, Philadelphia PA 19106. Exhibit hours are Tuesday, 11 a.m.-3 p.m.; Wednesday-Saturday, 11 a.m.-5:30 p.m.; Sunday-Monday, By Appointment.