Incarceration survivors pose with the Jerome monument.(Photo: Rob Buscher)

Part 1 of this two-part series sparks conversation

around the history of Jim Crow and

our own community’s wartime experiences.

By Rob Buscher, P.C. Contributor

In June and July 2024, I had the opportunity to attend both the Jerome/Rohwer and Tule Lake Pilgrimages. Taking place just under four weeks from one another, these two events expanded my understanding of the wartime incarceration in new and different ways, based on the unique geographic features, regional cultures and historic experiences that incarcerees endured at each site.

READ PART 2 HERE.

Adding an additional layer of nuance to these trips was the fact that my family recently discovered that a distant cousin of my Obaachan and his wife were incarcerated at both the Jerome and later Tule Lake camps. With this renewed appreciation for the significance of these sites in the context of my own family history, I embarked on the Jerome/Rohwer Pilgrimage that took place June 5-8.

Perhaps based on the geographical distance from both West Coast JA communities and the East Coast resettlers, the Arkansas camps have not historically held organized pilgrimages until Japanese American Memorial Pilgrimages began hosting them a couple years before the pandemic in 2018.

Certainly, the politics of the region as a former Jim Crow state may have deterred some would-be pilgrims from attempting such efforts earlier. The Governor of Arkansas during World War II, Homer Adkins, vehemently opposed the placing of WRA relocation centers in his state.

Whatever the case, few Japanese Americans have made the trek back to Arkansas until fairly recently. Having previously visited several of the former WRA sites in Western states, I was interested to see how the regional context would vary in the Jerome and Rohwer sites, which was something the pilgrimage organizing committee accentuated through their programming choices.

Hosted in the state capitol of Little Rock, the three-day pilgrimage featured a variety of local speakers and allowed participants to also engage with the vibrant Black civil rights history of the region.

The opening program on June 5 was a special workshop on Black reparations hosted by members of Nikkei Coalition for Redress/Reparations and Dreisen Heath, who previously led Human Rights Watch efforts toward Black reparations and is herself a descendant of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921.

The workshop powerfully grounded the pilgrims in overlapping history of racial oppression and gave helpful context for what the region’s most populous historically marginalized community was currently working toward in their own quest for reparative justice.

Akemi Kochiyama, the granddaughter of Yuri and Bill Kochiyama, gives the keynote address. (Photo: Rob Buscher)

Following the workshop at the opening dinner, we heard keynote remarks from civil rights activist Akemi Kochiyama, granddaughter of seminal activist Yuri Kochiyama, who was herself a former incarceree at Jerome. Included in the younger Kochiyama’s remarks were personal stories about her family’s multigenerational commitment to racial justice movements and a detailed account of the friendship between Yuri and Malcolm X.

After moving to Harlem in the postwar era, Yuri met Malcolm at a rally and invited him to visit her apartment when a group of hibakusha (atomic bomb survivors) from Hiroshima and Nagasaki were in New York to testify at the United Nations.

This visit sparked both a friendship that would last until Malcolm’s tragic death and an organizing partnership that expanded the vision and scope of both activists. The younger Kochiyama’s own work to preserve and share the story of solidarity and intersectional activism that her grandmother Yuri’s life embodies left the pilgrims with a meaningful call to action, before ending the first evening’s program with a short bon odori practice session.

Early the next morning, we boarded coach buses and departed for the former site of Rohwer, which is located about 100 miles southeast of Little Rock in the heart of the Delta, less than seven miles from the Mississippi River in former swamplands-turned-farm fields by incarceree laborers.

Panorama of the former Rohwer site (Photo: Rob Buscher)

Their efforts were so successful that the former site of Rohwer relocation center spent most of the last 80 years as cotton fields, before later being converted into soybean fields. Aside from the cemetery, which is listed on the national register as a historic landmark, and a single smokestack that once belonged to the hospital complex, nothing of the camp remains.

For a considerable portion of the ride there, we had the incredible fortune of listening to 98-year-old Mits Yamamoto recount his wartime experiences. Mits was 16 when Pearl Harbor was attacked and has a memory clear as the day it happened for much of his wartime ordeal. After being forced into the Fresno Assembly Center, he accompanied his family to Jerome camp. Shortly after the WRA began issuing temporary work leave permits, Mits spent time working in Chicago and later Florida.

After his job assignment concluded, Mits returned to Jerome to help his family pack their belongings when the Jerome camp was scheduled to close. Jerome was the last camp built and the first to close on June 30, 1944, with a peak population just under 8,500. The camp’s poor conditions in the Delta swamplands may have accounted for Jerome being the largest camp of No-No respondents to the loyalty questionnaire.

There were two stories that Mits shared with us that painted a particularly vivid picture of the harshness of camp life. As he was helping his family pack up their belongings, Mits smelled a horrible stench. When he went to investigate, he found the burning body of a Hawaiian Issei man who hung himself in a barn because he had nowhere else to go when the camp closed. Another was the story of a 2-year-old child who died from burn trauma after falling into a boiling vat of water in one of the laundry rooms.

Historic landmark plaque at Rohwer cemetery (Photo: Rob Buscher)

Still reflecting on these terrible experiences, the buses pulled into the Rohwer memorial cemetery where pilgrims spent about 90 minutes paying respects at the two dozen graves and Nisei veterans memorial. Compared to other sites like Amache, Topaz or Manzanar where the concrete foundations of barracks are still visible and visitors can access the entire grounds of the former prison camps, the Rohwer cemetery offers stark contrast to the total erasure of the wartime incarceration experience in Arkansas.

By the time we reboarded the buses, pilgrims were visibly suffering from the sweltering heat and high humidity of the Mississippi Delta. It was difficult to imagine living in such conditions for the three years this prison camp was in operation.

Next, we drove to the town of McGehee, whose population of 4,000 appears to be generally supportive of efforts to preserve this wartime history. Former Mayor Rosalie Gould led efforts alongside incarceration survivor George Sakaguchi in the early 1990s to designate Rohwer Cemetery as a national historic landmark, leveraging her relationship with fellow Arkansan and then-Gov. Bill Clinton to do so in 1992.

Later, Mayor Gould worked with incarceration survivors and descendants to establish a small museum in the old McGehee train station, located near the town center. It was here that our lunch program took place, with soul food dishes like fried catfish and hushpuppies catered by local food trucks.

Downtown McGehee, Ark. (Photo: Rob Buscher)

Current Mayor Jeff Owyoung, a third- generation Chinese American who has lived in the Delta for the last 40 years, gave welcoming remarks, followed by a performance from the Central Arkansas Taiko troupe.

The program concluded with a two-song mini-Obon, where the approximately 200 Japanese Americans danced the Tanko Bushi and Tokyo Ondo to honor our departed ancestors and those who were impacted by the incarceration in Arkansas. We then ended our time in McGehee by touring the Jerome Rohwer Incarceration Interpretive Museum, whose exhibit featured camp art and other artifacts donated by survivors.

From there we went to the Jerome camp, a further 15-miles south of McGehee, about a 30-minute drive from the border of Louisiana. Here for the first time, I stood on ground on which members of my own family were incarcerated.

My initial impression was shock at the total absence of what occurred in this space. Like Rohwer, the Jerome camp was all swamplands when the incarcerees arrived. After filling in the swamp with topsoil, the Issei and Nisei farmers toiled on this land to make it into productive farmland.

Shortly after the camp was closed, a farmer by the name of Ellington purchased the land and proceeded to remove the barracks foundations from the ground with a backhoe. As our buses pulled into the Ellington farm’s driveway, we were greeted by the son and great-nephew of the original landowner, who have pledged to make their lands available to visitors during the pilgrimage and other times when survivors or descendants have made their own solo trek to the site.

Aside from a large commemorative stone near the road and another smokestack from the Jerome hospital complex, no visible signs of the Jerome camp remain. As I meandered around the dusty access roads between the rows of soybean as far as the eye could see, I searched for any evidence of what had once occurred here.

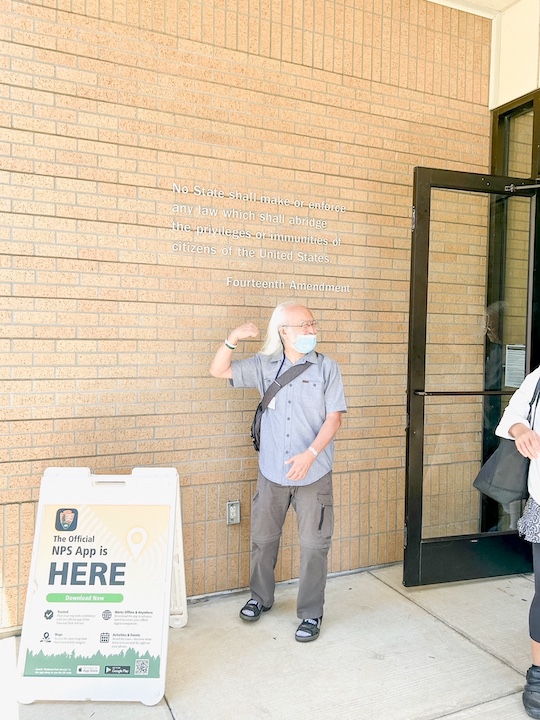

Survivor Al Harano outside the Central High National Historic Site. (Photo: Rob Buscher)

Finding none, my initial sense of numbness turned to frustration and even anger. It was as if the experiences of our cousins and the approximately 8,500 other incarcerees who were imprisoned at Jerome had never happened. If not for the commemorative stone, there would be no way of knowing what occurred here.

Still processing this complex mix of emotions, we left the Jerome site for the McGehee Men’s Club, where pilgrims enjoyed a barbecue dinner at the annual fundraiser for the Jerome Rohwer Interpretive Museum.

My earlier feelings of frustration melted into gratitude for the genuine Southern hospitality that our local hosts showed by welcoming us into their community. As we offered the local residents a glimpse of Japanese culture through the earlier Obon program, this was effectively their way of reciprocating a uniquely Arkansan cultural experience as we dined in a former Budweiser distribution warehouse. They then hosted a live auction where local farmers bid on yards of mulch, weed killer and other agricultural goods from whose sale the proceeds benefited the incarceration museum.

On the bus ride back to Little Rock, I marveled at the complicated combination of racially restrictive policies that had shaped and molded this region of the country, as some of the pilgrims shared reflections. We then watched the documentary “Relocation, Arkansas,” about the few Japanese American families who had stayed behind after the camps closed.

The next morning, our pilgrimage programs resumed at the Ron Robinson Theater in downtown Little Rock, located in the heart of the River Market District. There, we enjoyed a one-woman show by childhood incarceration survivor Connie Shirakawa, who regaled us with tales from her youth growing up on the South Side of Chicago after her family resettled there in the postwar era.

Other programs included presentations on the photographic record from the two Arkansas camps, a tribute to Mayor Rosalie Gould, a camp survivor panel and presentation on the Stockton Assembly Center.

That evening, ABC7 news anchor David Ono presented his multimedia theater presentation “Defining Courage,” about the Japanese American veterans of WWII. But since I had previously seen it at the 2023 JACL National Convention, I took this opportunity to do some local siteseeing on my own.

Given that we were less than three miles away from Central High School, where the infamous Little Rock Nine school integration case took place following the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, it seemed remiss not to visit.

I was pleasantly surprised to see no fewer than a dozen other pilgrims who decided to join the historic walking tour operated by the National Park Service. Starting with a short presentation by NPS Ranger Jazmyn Bernard, we then walked over to the grounds of Central High.

Ranger Bernard proceeded to tell us in painstaking detail the vitriolic hate speech and threats of physical violence that the Black children endured simply for attempting to attend school. At one point in the tour, Ranger Bernard walked backwards in front of us, shouting obscenities and other hate speech that the white supremacist protestors yelled at Elizabeth Eckford, the 15-year-old girl pictured in the renowned photos of the Little Rock Nine. I was not the only one of the pilgrims moved to tears as we caught a brief glimpse into the daily realities of Black Americans living in the Jim Crow South.

Following my visit to Central High, I had the opportunity to tour the Black history museum located at the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center, where I learned more about the history of school integration and the role that Booker T. Washington played in the Black school movement of the pre-civil rights era.

Speaking with the museum docents, I learned that several other pilgrims had also visited the museum during that weekend. We shared a quiet moment of reflection in the shared community histories of our respective traumas in this state.

Walking back to the pilgrimage hotel just a couple blocks from the Mosaic Templars, I encountered a sign for the Mount Holly Cemetery that proudly proclaimed it to be the final resting place of four Confederate Generals. Suddenly, the absence of wartime incarceration history at Jerome did not seem so bad when I considered the immense pain that Black Americans must encounter on a daily basis when facing reminders of Arkansas’ past.

The final day of the Jerome Rohwer Pilgrimage began with a keynote presentation by Frank Abe, followed by additional opportunities to connect with fellow pilgrims, including an intergenerational group discussion, farewell dinner and social gathering.

In the three weeks between these events and the start of my next trip, I frequently revisited the moments during that pilgrimage when I had opportunities to engage with local Black residents in Arkansas in conversation around the history of Jim Crow and our own community’s wartime experiences. It has since led to many interesting conversations with our comrades from N’COBRA Philadelphia and other allies working toward Black reparations within the JACL Philadelphia chapter.

With these lessons and aspirations toward solidarity fresh in mind, I left for the San Francisco Bay Area on July 1, where I would later depart for the Tule Lake Pilgrimage.

Editor’s Note: Part 2 of this series will be featured in the Sept. 6-19, 2024, issue of the Pacific Citizen.