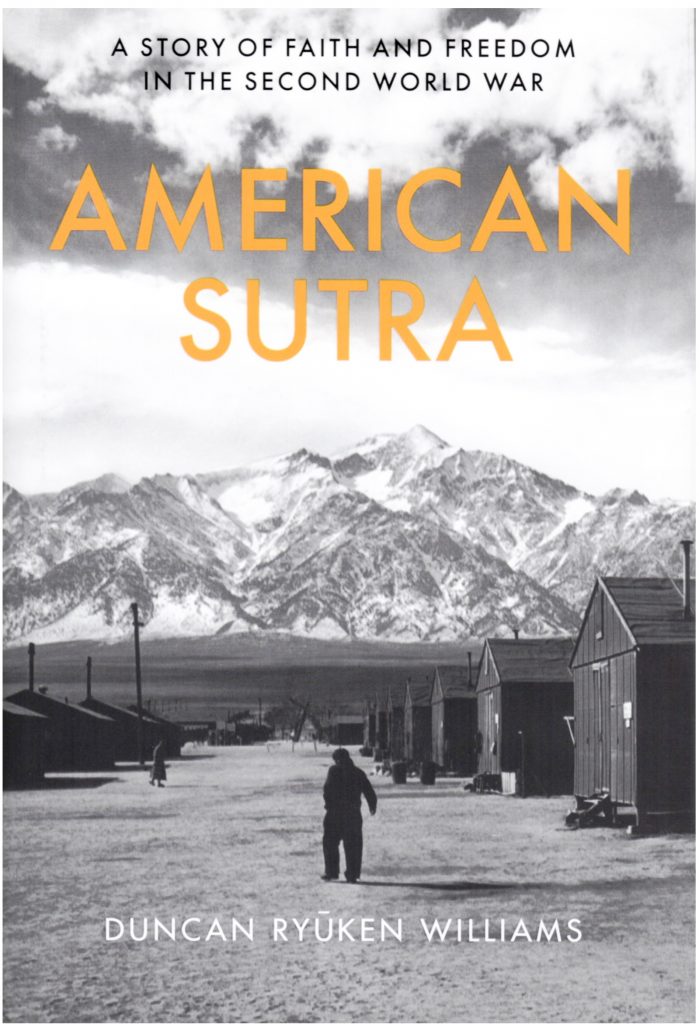

Duncan Ryūken Williams points to a photograph of Rev. Shinjo Nagatomi conducting a Buddhist service at Manzanar during World War II. Williams used the photo while discussing “American Sutra.” (Photo: Pacific Citizen)

‘American Sutra’ examines the WWII struggles of Japanese American Buddhists.

By P.C. Staff

Tibet’s Dalai Lama on the cover of a recent issue of Time Magazine. The House of Commons’ John Bercow exhorting for “zen” earlier this year during a tumultuous session on Brexit at Britain’s Parliament. Words such as “karma” and “mindfulness” being found in casual speech.

In 2019, what do the aforementioned share? A link to Buddhism.

“It’s almost fashionable,” said Duncan Ryūken Williams, referring to how Buddhism and Buddhist ideas are subtly and not so subtly now embedded in everyday American life.

However, as Williams — a professor of religion and East Asian languages and cultures at the University of Southern California and an ordained Buddhist priest in the Sōtō Zen sect — pointed out, it wasn’t always so.

Williams made the comment at the Japanese American National Museum’s Tateuchi Democracy Forum in Little Tokyo on Feb. 23 during a discussion for his new book, “American Sutra.”

Subtitled “A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War,” the tome, which was 17 years in the making, is a historical examination of how the Buddhist beliefs of the majority — more than two-thirds, according to Williams — of American-born Japanese and their Issei parents (who were at the time ineligible to become naturalized U.S. citizens) in the then-territory of Hawaii and the mainland United States added another layer of “otherness” to existing ethnic and racial differences between Japanese immigrants (and their American-born offspring) and America’s white, Christian majority.

When the U.S. declared war on Japan on Dec. 8, 1941, following the previous day’s attack on Pearl Harbor, that “otherness” would lead to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, which would remove tens of thousands of ethnic Japanese living on the American West Coast to remote inland concentration camps operated by the federal government.

Not only would what would happen to ethnic Japanese in America during the fifth decade of the 20th century prove to be an ordeal of epic proportions for that population, but it also forced America to face questions about the meaning of U.S. citizenship and the inherent rights citizenship conferred.

The Japanese American experience during WWII also pit bedrock American principles and constitutional rights such as due process, equal treatment under the law and religious freedom against populist notions of who could be an American and what belief system an American should follow.

As the nation again faces those fundamental questions in the 21st century, Williams’ “American Sutra” has arrived to revisit the history of how a population that was neither white nor, for the most part, Christian, grappled with those same issues decades ago.

When Roosevelt issued E.O. 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942, it would take months before the majority of West Coast Japanese Americans would be sent to assembly centers and then War Relocation Authority camps.

Williams pointed out, however, that there was no such time lag for Japanese community leaders, who were questioned and arrested, in some cases within hours of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

“The very first person the FBI visited, even before the smoke had cleared at Pearl Harbor, at 3 p.m. on Dec. 7, 1941 — they arrested Bishop Gikyō Kuchiba, the head priest of the Honpa Hongwanji Buddhist Temple in Honolulu,” Williams said. “All of the different Buddhist priests — the Nichiren sect, the Shingon sect — were arrested within hours of the Pearl Harbor attack.” Shinto priests were also targeted.

That the U.S. government could act so quickly was because it was a foregone conclusion, Williams said, that war with Japan would happen.

“This was not some kind of panicked response to what was, admittedly, a surprise attack. The Office of Naval Intelligence, the Army G-2 Military Intelligence, as well as the FBI, had all assumed that war with Japan would be coming,” Williams said. “There was a calculation with the U.S. government’s intelligence agencies that war with Japan was inevitable, and from as early as the late 1930s, they had begun to consider who would be arrested in case war with Japan happened.”

Duncan Ryūken Williams with (from left) Brian Niiya, Valerie Matsumoto and Naomi Hirahara at the Tateuchi Democracy Forum panel discussion. (Photo: Pacific Citizen)

Joining Williams to discuss “American Sutra” were Naomi Hirahara, a writer of books on Japanese American history and an award-winning mystery novelist; UCLA professor Valerie Matsumoto, the George and Sakaye Aratani Endowed Chair on the Japanese American Incarceration, Redress and Community; and Brian Niiya, content director for Denshō.

“I’m grateful for Duncan tackling one of the most-challenging and neglected aspects of the incarceration story,” Niiya said, noting that while there exists “a tremendous amount of literature” on the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans, there are “wide areas of the subject that we don’t know a whole lot about.”

Niiya lauded “American Sutra” for including the experiences of ethnic Japanese both in Hawaii and the U.S. mainland in the same book and that Williams was in the “unique position” to be able to use sources, such as personal diaries of Buddhist priests who had been incarcerated, to tell stories that few people before had heard.

Niiya also praised “American Sutra” for being able to give a different perspective on the service of Japanese American soldiers who served during WWII in the 100th Battalion/442nd Regimental Combat Team and the Military Intelligence Service, something he “didn’t think was possible to look at in a different way, but looking at it from this Buddhist framework does make you see these familiar stories in a unique way.”

For Matsumoto, “American Sutra” was important for how it “illuminates the significance of Japanese American Buddhists and the struggle for religious freedom in the U.S.” She was also captivated by its “range and the richness of the voices that Duncan has painstakingly gathered and presented.”

The book also struck a personal chord for Matsumoto, whose uncle, Masami Hayashi, was a Nisei who served in the MIS during WWII. She related a story told by her uncle that she said revealed her uncle’s Japanese cultural knowledge and Buddhist ideals.

The book also struck a personal chord for Matsumoto, whose uncle, Masami Hayashi, was a Nisei who served in the MIS during WWII. She related a story told by her uncle that she said revealed her uncle’s Japanese cultural knowledge and Buddhist ideals.

In her uncle’s words, Matsumoto related how a former criminal investigator from Chicago was ready to use a blackjack on a Japanese POW if he didn’t talk.

“I informed the investigating officer that the best way to get cooperation from a Japanese prisoner of war is to treat him kindly. Give him a cigarette or candy. With this kind treatment, he will be appreciative and give you full cooperation,” she related. “To the officer’s surprise, the prisoner gave full cooperation and responded willingly.”

Hayashi went on to have a career as a research metallurgist at the U.S. Bureau of Mines and after retiring became a Jōdo Shinshū priest.

Hirahara, who described herself as a “Christian convert” whose great-great grandparents led a Buddhist temple in Japan, said the book “really takes us to task” on how politicians and “just your regular individual” can discriminate against religions that are not Christian. “As a Christian myself, I need to take heed and pay attention,” she said.

Hirahara also noted that Williams’ Buddhist viewpoint put a “fresh new twist” on something familiar to scholars. “You know the Japanese word atarimae?” asked Hirahara, referring to a word that can be translated as obvious. “There were so many soldiers in the 100th and 442nd Regimental Combat Team that were Buddhist. Atarimae, right? Most of us were Buddhist, so of course. But it didn’t really dawn on me.

“Reportedly, 70 to 80 percent were, according to Duncan’s research, and 400 of the 506 Hawaii-born killed in action were Buddhist, yet there was no Buddhist chaplain on the frontlines,” she continued. “I didn’t really think about that. I guess that’s the Christian privilege in me.”

For Williams, the 17-year-long odyssey to write “American Sutra” began after the death of Harvard College professor Masatomi Nagatomi, who was Williams’ grad school adviser. Williams was one of the last students of Nagatomi, who had taught at Harvard since 1958.

While assisting professor Nagatomi’s widow, Masumi Nagatomi, with some of his papers, Williams came across a diary, written in Japanese, by the professor’s father, Rev. Shinjo Nagatomi, while he was incarcerated at the Manzanar WRA Center.

“As somebody who was born in Tokyo to a Japanese mother but to a British father and only came to the United States when I was 17, I didn’t have any personal or family connection to the Japanese American incarceration story,” Williams said. “It was just by chance that I came across it.”

When Masumi Nagatomi asked Williams if he would translate some portions of the diary into English to help the family understand more about Professor Nagatomi’s father, he said he knew that in order to understand the significance of what he was holding, he would need to understand the broader context of the Japanese American incarceration experience during WWII.

“All I knew was that my professor had somehow, without having ever disclosed its existence to his wife, kept these diaries and Buddhist sermons of his father in his office all those years,” Williams said.

After translating parts of the diary for Professor Nagatomi’s survivors, Williams said some other families with fathers or uncles who were also Buddhist priests during the war approached him to translate their diaries.

But it was only after getting the full story from Masumi Nagatomi about an incident from her childhood did the idea of writing a book about that broader context of the challenges of being Japanese American and Buddhist during WWII occur to Williams.

In the days after the Pearl Harbor attack, Masumi Nagatomi, née Kimura, told him she came home from school to find her father, who was a board member of the Madera, Calif., Buddhist Temple, pinned to the ground by one man as her mother sat at the kitchen table with another man holding a gun to her head.

Duncan Williams holds a copy of “American Sutra” after signing it for Iris and Ron Gee following his book discussion. (Photo: Pacific Citizen)

“Even though she was only 10 years old, she knew she had to step in there because her parents, being from Wakayama Prefecture, immigrants from Japan, didn’t have much facility with English,” Williams said.

As it turned out, it was a horrible misunderstanding caused by a case of bad timing — her father was stepping out of the house with a shotgun to scare away rabbits in their fields just as FBI agents sent to question her father arrived at their farm.

To prove his family’s loyalty to America, her father burned most of their belongings that were made in Japan, or had on them Japanese writing or cultural significance — but not the Amida Kyo sutra that had been in the family for generations, as well as the Madera temple’s minutes from its founding onward. Those papers he wrapped in a kimono cloth and put into a senbe tin to be buried near the garage, hoping that he could someday recover them.

The Kimura family sold the farm and escaped incarceration by moving to Utah to be farm laborers. When they returned after the war, the new owners had torn down the garage, which made finding the buried sutras impossible.

Williams now had a mission, which was to write a book that would honor stories like that.

“To me,” Williams said, “this story is about one Japanese American Buddhist family trying to demonstrate their loyalty and belonging to the United States, even literally burning away their Japanese-ness, but refusing to burn away their faith, their Buddhist faith, asserting in their own way that it would be possible, that it could be possible that one could be a Buddhist and an American at the same time.”