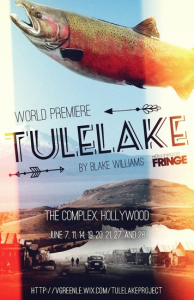

Angelina Rangel (center) performs in “Tulelake” at the Complex as part of the Hollywood Fringe Festival.

Presented at the Hollywood Fringe Festival in June, the play ‘tells a story that needs to be told.’

By Connie K. Ho, Contributor

“Witness our last breaths.”

“Tell them of Tule — tell them of Tule Lake.”

These are just a few of the lines chanted and shouted in “Tulelake,” a play that was presented at the Hollywood Fringe Festival in June and highlights the stories of communities in Tule Lake, Calif.

The impactful work weaved together the stories of Japanese Americans, indigenous groups and fishermen. During the three-act play, the audience was introduced to scenes in the Tule Lake Internment Camp (1942-46), arguments among groups related the Modoc War (1872-73) and the negative effects on the fish species in the Klamath River (2002). To keep the story moving smoothly from one time period to the next, the costumes for the show were simple, stylized and free-flowing. Director Blake Williams utilized a mixed-colored palette in the dress, including neutral colors, army green and more stark red, white and black.

Williams’ connection to Tule Lake stems from her family. Her father was a history teacher, and she was raised with a fascination for the lost histories that humanity forgot to tell. When Williams was in college, her father remarried, and she found herself half-Japanese by marriage. Her step-great grandmother, Ruth Kinoshita, was interned at Heart Mountain, and she met her husband there.

“The stories she told fascinated me,” Williams said. “So began my fascination with Japanese theater. I was moved by the respect, tradition and training that goes into Noh and Kabuki theater forms — I enjoyed playing with stylistic rules that govern Noh and Kabuki and juxtaposing them against the existential playwriting I was doing as an undergrad.”

In order to fit the play into the tiny Complex space and meet Fringe requirements, Williams incorporated stylistic elements using fabric as smoke and water.

The journey to performing “Tulelake” in the Hollywood Fringe Festival spanned more than a decade. “Tulelake” grew out of a Japanese theater class that Williams took at Humboldt State University as part of her masters in fine arts program in directing.

During that class, she worked with a MFA writing student of Japanese descent; they started writing the “Tulelake” piece in Haiku for their final project and finished the original word piece in 2003. Williams made the decision to put together the show last winter, while also juggling a directing and teaching schedule at San Marino High School in San Marino, Calif.

“The fact that I just finished this show after 13 years of trying is a truly amazing feeling. I’m always proud of my shows, but with ‘Tulelake,’ I felt like I fulfilled a promise,” Williams said.

In January, Williams began by working on the script with her advanced drama class. Once a week, the group would sit in a circle, reading aloud, asking questions and even rewriting parts of the piece. Then, in March, she staged a reading with a group of adults and students. The rehearsal process took place over the next few months in preparation for the performance at the Complex in the Hollywood Fringe Festival.

“The hardest part was fitting the show into the tiny Complex space. I had to make the show even more stylistic to accommodate the Fringe requirements, using fabric as smoke and water and filming intelligent light cues,” Williams said.

The cast was a diverse group, with amateur and professional actors, young and old, those of Asian descent and others of mixed backgrounds.

“I think this play is great — it’s superinformational, and it tells a story that needs to be told. Beforehand, I didn’t know a lot about Tule Lake,” said Jack Nixon, a San Marino High School 2015 grad who will be pursuing a theater studies degree in the fall at Emerson College in Boston. “Upon reading the script, I learned that there was so much that happened there that hasn’t been known by the public — I thought it would be cool to tell this story and inform people about this tragedy but also the hope.”

The performance was especially meaningful to Pogo Saito, one of the cast members whose family was personally affected by the relocation of Japanese Americans in World War II.

“My dad was at Tule Lake before [staying at Heart Mountain], so I always have an interest to tell that story,” Saito said. “This year, my dad passed away, and I really felt the power of telling the story of someone who can’t tell their story. It was probably one of the strongest moments for me as an actor to realize that.”

Saito believes that the play is important in evoking stories of the past.

“I think we’re like rippling on the pond — if everyone keeps telling this story, it’ll just keep going. We always feel like we’re powerless as one person, but we’re very powerful, and I think that’s a story to tell, and it’ll keep rippling. There are people coming into this room every night, and they don’t know this story and any of these subjects — now they go out into the world knowing these things,” Saito said. “More knowledge is powerful for everyone. It feels like responsible theatre — theatre is part of change, the idea that you put it out there, which creates the catalyst for things to evolve.”

Williams herself hopes to continue to work on, develop and showcase the play.

“I would love to start in Seattle and tour the West Coast with this show, hitting colleges, the internment camps and museums, telling the story that has been forgotten,” Williams said. “I would love to take the time to finally incorporate the cultural elements. I would love to spend weeks in Tule hiking and creating film and images. I would love to take a group of actors, or a college class, or committed company and finish this story.”

To Williams, “Tulelake” and other plays are essential in bringing the community together.

“I believe in necessary theater, theater that is essential and a mirror into our humanity. ‘Tulelake’ was necessary for me — I have felt like I was supposed to tell its story or no one else would,” Williams said. “The play is not about making the audience feel bad about the past or guilty. It is about inspiring people to think, remember and tell the lost stories of our past. The world is changing, and as I look into my student’s eyes, I wonder how I can make the world a better place.