Delicious food offerings await attendees of the 2023 Nikkei Community Picnic, which is

sponsored by organizations and businesses of the Nikkei community to celebrate Japanese American heritage. (Photo: Rich Iwasaki)

The Japanese American community in Portland’s

commitment to collaboration is key to its success.

By Emily Murase, Contributor

What are the defining characteristics of the Japanese American community in the Portland area? Members of the Portland JACL board of directors, past and present, and community leaders agree that a commitment to collaboration, both within the Nikkei community and with other communities, is key to the many circles of trust.

“There is a lot of crossover among leaders of community organizations,” said JACL Portland President Jeff Matsumoto, a Yonsei who moved to Portland from California eight years ago. “Our chapter members are involved in the Japanese Ancestral Society and the Portland Japanese Gardens and the Nisei Veterans Group. This crossover helps us to be connected.”

Portland JACL board members Jeff Matsumoto (left) and Amanda Shannahan speak with young visitors on July 27, 2019, at Natsu Matsuri in Beaverton, Ore. The annual festival features a variety of organizations presenting numerous aspects of Japanese and Nikkei heritage and culture. (Photo: Rich Iwasaki)

Setsy Larouche, who first arrived to Portland from Japan in 1955 and has served as JACL Portland’s membership chair for 20 years, explained, “To celebrate graduating high schoolers, 11 community organizations sponsor the Japanese American Graduation Banquet. Can you imagine that this is the 77th year of this event?” Similarly, what had been disparate community gatherings for many years has come together as the Annual Nikkei Community Picnic, a free event that attracts hundreds of community members.

Citizens and residents carry banners on Jan. 28, 2017, at the March for Justice and Equality along Martin Luther King Boulevard in Portland. Members of numerous organizations, including Portland JACL, participated in the march. (Photo: Rich Iwasaki)

Former JACL Portland President Marleen Wallingford, whose family has lived in Oregon for generations, said, “Our chapter is deeply committed to collaboration and is constantly reaching out to other communities. In the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd, we reached out to the Black community and are supporting efforts around Black reparations. We launched an anti-racist book club that started with Ibram Kendi’s book ‘How to Be an Antiracist.’ Earlier, in the weeks after 9/11, we reached out to the Muslim Educational Trust.”

Larouche and Wallingford recount an episode from the Portland JACL chapter archives that explains the motivation for this kind of chapter activism. “The day after President (Franklin D.) Roosevelt delivered the ‘Day of Infamy’ speech in the wake of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the principal of Lincoln High School addressed the entire student body with similar rhetoric. My uncle, among the students in the assembly that day, including many Nikkei students, wrote about it in his diary how he felt targeted and uncomfortable.”

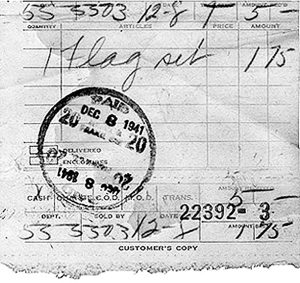

A receipt for a U.S. flag purchased by the Portland JACL chapter, dated Dec. 8, 1941 (Photo: Courtesy of Setsy Larouche)

In going through chapter archives, Larouche came across a very memorable receipt. “If you look at the date stamp, it says Dec. 8, 1941, the day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. On this day, the JACL chapter purchased a U.S. flag from the Portland-based Meier & Frank Department Store.” She recalls that the flag was eventually donated to Portland State University many years later.

Like the Portland JACL chapter, the Portland-based Japanese Ancestral Society is also highly collaborative, and its leadership reflects the crossover that Matsumoto has described.

Current Japanese Ancestral Society President Rich Iwasaki is a former Portland JACL president and a professional photographer who can be seen at nearly all Nikkei community events. He echoes the sentiment of current chapter board members: “While there is no Japantown/Nihonmachi in Portland anymore, we are such a small community that we see each other all the time.”

According to Kourtney Goya, writing from the Oregon Encyclopedia, the Japanese Ancestral Society of Portland has its origins as far back as 1907, when large numbers of Japanese immigrated to Oregon. By 1910, more than 3,500 Japanese immigrated to the Portland area seeking work on railroads, in canneries, logging in forests and farming one of the 83 Japanese-owned farms that controlled more than 4,600 acres in the state.

Members of Portland JACL assemble annual calendars in 2014 to be sent to chapter members (Photo: Rich Iwasaki)w

Among those farmers were Matsumoto’s paternal grandparents, who immigrated from Shiga Prefecture in the early 1900s. “Building on the work of my Issei grandparents, my father and his two brothers formed the Iwasaki Brothers wholesale nursery, which remains one of the largest in the Northwest,” explained Matsumoto. The nursery celebrated its centennial in 2016.

Matsumoto’s maternal grandparents ran a small hotel in Portland Japantown/Nihonmachi, which provided all manner of social services to Japanese newcomers, including job referrals. Henry Sakamoto, in his research featured in the Oregon Encyclopedia, writes that there were actually two Nihonmachis in Portland, not only in the northwest district but also in the southwest. Both were thriving commercial and residential neighborhoods up until World War II when the incarceration left both places ghost towns.

The Monument to Nikkei Veterans at the Japanese Cemetery during the Memorial Day ceremony in 2018 (Photos: Rich Iwasaki)

With Japanese immigration to Portland came the need for a dedicated burial place. Due to raciswm and segregation, the Japanese community needed its own place to bury the dead. The Japanese Ancestral Society stewards the Japanese cemetery on land purchased by the Nikkei community and organizes an annual Memorial Day service in partnership with the Portland JACL and several other Nikkei organizations.

The Society also funds and staffs the Ikoi no Kai, a community hot lunch program offering an Asian menu including pork katsu, Hawaiian loco moco and Korean bibimbap, on-site, four days a week for just $9 for seniors 65-plus, $11 for adults under 65 and $6 for kids. A monthly bento lunch delivery service is also offered to home-bound seniors. With just a few part-time staff paid by the Society, the program relies on a team of dedicated volunteers. This year, Ikoi no Kai celebrates 45 years of service to the community.

Unite People, the youth group affiliate of Portland JACL, with Sec. Norman Mineta in 2014 after receiving a JACL Legacy Fund Grant at the 2014 JACL National Convention in San Jose, Calif. (Photo: Rich Iwasaki)

The program is held at the Epworth United Methodist Church, which was founded by Japanese immigrants in 1893. According to George Azumano, writing for the Oregon Encyclopedia, the number of Issei in the Portland area began with 30 in 1887 and tripled to 100 in 1892. The Japanese Methodist Episcopal Church in San Francisco sent Rev. Teikichi Kawabe to visit Portland three times, after which the church decided to open the Japanese Methodist Mission.

By 1903, a church building was purchased using a combination of local donations of $2,500 and $3,500 from the Methodist Episcopal National Board of Missions. The church moved to its current location at 1333 S.E. 28th Ave. after purchasing the property for $20,000. In 2011, 95 percent of the 200-plus congregants identified as Japanese American, according to Azumano. The church has hosted Ikoi no Kai since 1985.

A relative newcomer to the Portland Nikkei community is Hanako Wakatsuki-Chong, who became executive director of the Japanese American Museum of Oregon in July 2023 after serving as the superintendent of the Honouliuli National Historic Site in Hawaii and as a policy adviser on Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Affairs in the Obama White House.

A Nihonmachi display at the Japanese American Museum of Oregon (Photo: Rich Iwasaki)

Formerly known as the Oregon Nikkei Legacy Center, JAMO has the mission to “preserve and honor the history and culture of Japanese Americans in the Pacific Northwest, educate the public about the Japanese American experience during WWII and advocate for the protection of civil rights for all Americans.”

The impetus for preserving Oregon’s Nikkei history can be traced to the 1973 Issei Appreciation Project that gathered documentation of Issei before the 1924 ban on Japanese and other Asian immigration by the federal Immigration Act.

Then, according to Sakamoto, in 1988, the City of Portland embarked on plans to expand the Tom McCall Waterfront Park near the location of the northwest Japantown. These plans involved a collaboration between the Oregon Nikkei Endowment (now the Japanese Ancestral Society), the Japanese Business Assn., the Japanese American Citizens League, other Nikkei community-based organizations, multiple city departments and local foundations.

The resulting Japanese American Historical Plaza, dedicated in 1990, features 13 granite and basalt stone monuments engraved with poems by Nikkei poets memorializing the struggles of Japanese Americans in Oregon.

Two reunions of Oregon Nikkei in 1990 and 1995 attended by 900 and 700 individuals, respectively, created additional momentum for creating video documentaries and mounting historic exhibits about the Japanese American experience in Oregon and gave rise to the idea of the Oregon Nikkei Legacy Center.

Through the generosity and advocacy of local business leaders Bill and Sam Naito, a location for the center was secured in 2004. However, to accommodate expanded exhibit space and fulfill a strong desire to locate in the former Nihonmachi area, the center was renamed the Japanese American Museum of Oregon and moved to its current site, the Naito Center, at 411 N.W. Flanders St. in Old Town in May 2021.

A Minidoka barrack on display at JAMO (Photo: Rich Iwasaki, Courtesy of JAMO)

The exterior of the Japanese American Museum of Oregon (Photo: Rich Iwasaki, Courtesy of JAMO)

JAMO features a permanent exhibit that immerses visitors in the everyday lives of Japanese Americans before, during and after WWII. Highlights include a Minidoka barrack and the actual cell where celebrated civil rights champion Minoru Yasui, then a 26-year-old law school graduate, was held in solitary confinement for nine months, according to the Oregonion newspaper. The museum is a beloved cultural, artistic and historical hub for the Japanese American community.

Wakatsuki-Chong talks about how special the Portland Nikkei community is compared to other places: “I am extremely impressed with the level of collaboration here, a level that I haven’t seen before. I find it so refreshing and inspiring. This ability to work together provides the Japanese American community in the Portland area with great strength and leads to effectiveness.”

She cites the example of Oregon House Bill 4085, which would create a $6 million fund to offset the cost of applying for permanent U.S. residency (green card status). She found strong support among other Japanese American organizations for this legislation as leaders recognized the importance of advocating for immigrants and nonresidents.

Holly Yasui speaks during the commemoration of Minoru Yasui Day on March 28, 2017, in the atrium of Portland City Hall. (Photo: Rich Iwasaki)

Wakatsuki-Chong explains that she first became interested in the work of the JACL when she joined Friends of Minidoka while in college in Idaho, where she spent her formative years. Reflecting on her partnership with the Portland JACL, she points to “Nobi’s Night Out,” a 1920s speakeasy-themed fundraising gala for the museum that was held last year in honor of the late Nobi Masaoka, a very active JACLer.

A 2023 Nobi’s Night Out fundraiser flyer (Photo: JAMO)

According to the most recent American Community Survey (2014), the population of Portland was 602,568, of which 2,869, or 6 percent, identified as Japanese. Yet, the Portland JACL has a membership of more than 400 people, a membership that is larger than chapters where there are many more Japanese Americans in the general population and, in fact, making it the largest JACL chapter in the country.

Clearly, the Portland JACL plays a central role in the circles of trust that define the Nikkei community in the Portland area, and the chapter’s success can be attributed to its extraordinary commitment to working collaboratively throughout the Nikkei community and beyond.