This preliminary rendering shows the Irehi or Spirit Consoling Structure early in the design process, with projection technology and gold fracture line designs.

The Irei Names Monument seeks to make visible what was once erased — all the names of the Japanese Americans incarcerated.

By Lynda Lin Grigsby, Contributor

In 1903, on a ship bound for the United States, Ayaka Takahashi — as the ship’s manifest identified him — befriended a passenger who questioned the need for the vowel at the end of his surname if it wasn’t pronounced. Japanese, like many languages, is amorphous. Sometimes the “i” at the end of the word speaks, but sometimes it is silent. As the story goes, the Issei took the “i” and dropped it in the Pacific Ocean, and the waves carried its superfluousness away. He became Ayaka Takahash.

“It was a deliberate choice made by my grandfather,” said Janis Hirohama, a South Bay JACL member. “And it is a meaningful part of our family history.”

Takahash’s reclamation of his name signified a rare form of agency during a time when Japanese American names and identities were often changed because of U.S. government misspellings or lexical gaps. A misspelling can live for generations and render a person into abstraction until the name is taken back.

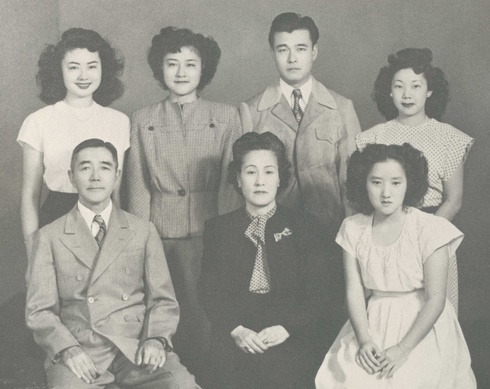

Ayaka Takahash (seated, left) with his family in 1946.

What if we can take back our names like Takahash by throwing out unnecessary letters, crossing out misspellings and writing in the correct spelling? Would that simple act of reclamation plant a seed of healing?

A first of its kind memorial to honor all Japanese Americans who were incarcerated during World War II seeks to answer those questions by establishing a master list of incarceree names. We know official records often cite that 125,000 Japanese American people were forcibly evacuated, but up until now, the records have been a scattering of camp intake forms, draft cards, even camp rosters handwritten by incarcerees — but no master list of all incarcerees existed.

It makes the historical event — a lived experience in your families — an abstraction experienced by what Duncan Ryuken Williams calls an “undifferentiated mass who were guilty by association.” This pain can only be repaired if names are given back.

Spearheaded by the USC Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture, with Williams as the director, the Ireichō, or “Book of Names,” is one part of the ambitious memorial funded by the Mellon Foundation to bring into focus the individuals behind the undifferentiated mass. The faceless people on the scattering of records, reduced to numbers written on tags, were people like Takahash who suffered, loved and laughed. In the Ireichō, his name will be listed as he intended.

A Healing Memorial

Another preliminary rendering of what the Irehi or Spirit Consoling Structure may eventually look like.

The Irei Names Monument seeks to make visible what was once erased. The USC Shinso Ito Center received a $3.4 million grant over three years from the Mellon Foundation to build the memorial.

The idea borrows from the Buddhist tradition of writing and recitation of ancestors’ names as an act of bringing the past and the present together. For a community to be made whole, we must count every individual, said Williams, a Soto Zen Buddhist priest and scholar.

The memorial will be composed of three elements:

Ireichō or the Book of Names: The master list of names of all the people incarcerated during WWII — including Department of Justice camps — will be completed in June. The list then goes to the book’s design team — Jon Sueda and Chris Hamamoto from the California School of the Arts in San Francisco. The names will be sequenced by age, starting with the oldest Issei and ending with the last baby born behind barbed wire. This sequencing gives a sense of the community at the camps, said Williams. In September, three bound books, which will be Gutenberg Bible size, will be displayed at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo.

Ireizō or Consoling Spirits Website: The beta version of Ireizo.com will launch in the fall to provide more details of individuals incarcerated during WWII. Here, the names will be listed in alphabetical order and mapped to camps and additional information from Densho archives. The full version will launch in 2023.

Ireihi or Spirit Consoling Structure: Like the memorial at the Manzanar National Historic Site, the Ireihi will encourage pilgrimages. Seven small-scale monuments will be installed at confinement sites and visitors’ centers starting in 2024. A large-scale version of the monument will be unveiled at JANM in 2025.

The Ireihi Names Monument will be born during a time when many are rethinking memorials. The idea came out of the movement to think beyond monuments as permanent and static — like Abraham Lincoln sat down and never got up despite history continually being reinterpreted around him. This memorial will be dynamic and interactive, said Williams. Names will scroll and change. The idea is to take this memorial beyond remembrance to repair.

What is this memorial trying to repair? First, it seeks to correct misspellings. Surnames like Matsukuma became Matsuguma with the click of a typewriter key.

“The way we don’t honor those who have come before us is by replicating the errors, which are unfortunately replete in these government rosters,” said Williams.

During WWII, Japanese American names were taken away and replaced with unique numbers. The memorial also seeks to restore full identities.

According to Janis Hirohama, the memorial is about so many individual stories. She is pictured at the 2018 Poston Pilgrimage with her family’s memorial brick.

“Names matter,” said Hirohama, a Sansei Buddhist minister’s assistant. During WWII, her grandparents were incarcerated at Poston. “My family is more than ‘Family Number 41919.’”

Getting to 99.9 Percent Accuracy

In 2019, Williams wanted to organize a collective national moment of chanting and recitation of the names of the 125,000 victims of the WWII incarceration — all he needed was a master list of names. It was a moment of ambitious idealism that quickly ended when he found out no such list existed.

Well, he thought to himself, I guess I need to create it.

“I see why nobody’s ever done this,” said Williams. “It’s such a massive undertaking.”

To put together an accurate master list of former WWII incarcerees meant gathering rosters from the main War Relocation Authority camps and the Department of Justice camps — which rarely get included in the official count.

During the war, individuals and families often transferred from camp to camp, creating a confusing spiderweb of information that the memorial’s 12-person team picked through and cross-checked with a complex flow chart.

The goal was to determine with 99.9 percent certainty what the actual number of persons of Japanese ancestry were incarcerated in any confinement sites, said Williams. Among the records he came across were camp rosters written in Japanese script that included information about a person’s name and address before the incarceration. Romanizing the names was not as easy as it sounded.

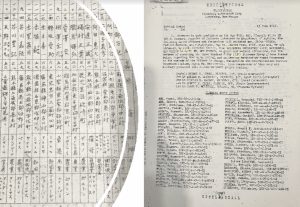

Translators went through handwritten camp rosters like this one from the Lordsburg camp.

“Although there were typical names that I could easily decipher, there were also a number of cases where a character could be read in a few different ways,” said Yukari Inoue Swanson, a translator and research assistant on the project.

“I had to make the best guess with the consideration of name trends in the late-19th century.”

Through the verification process, Williams created a series of rules to help guide the team in its decision-making process. One rule he calls the “rule of historicity” calls for the use of the name that was correct at that time. When Williams came across Takahash’s name, it raised a red flag. By chance, he knew Hirohama, who told him about the dropped “i” in the Pacific Ocean, so Takahash’s name remained in the book of names as intended.

Kintsugi and Community Interaction

The Sept. 23 Ireichō installation at JANM will have all the pomp and ceremony of a religious procession. The vision is clear, but the exact route is yet to be determined. A group of clergy members will carry the books from Maryknoll Japanese Catholic Center to JANM.

During WWII, Maryknoll and the site of the old Nishi Hongwanji Temple — now the plaza in front of JANM — were gathering spots for transportation to both the Santa Anita Assembly Center and Manzanar.

The healing power of the memorial will lie in the interaction with its audience. In a Japanese tradition called kaigan, artifacts are enlivened through interaction. For a year after the book of names installation at JANM, survivors and their family members will be invited to correct misspellings, add names that may have been omitted, as well as add gold lines on the glyph between each name. Each gold line — a symbolic link between the past and the present — honors the memory of the person.

“It’s such a massive undertaking,” said Duncan Ryuken Williams about the process of creating a master list of all Japanese Americans incarcerated during WWII. He is pictured in 2021 going through the WRA’s Final Accountability Roster.

“It’s a way of involving the community to correct the record and repair the history,” said Williams.

Repair is transitory. It changes and morphs. Another Japanese tradition called Kintsugi calls for the repair to be visible and celebrated. When a bowl or teapot breaks, it is fixed with gold-adorned fracture lines.

The memorial in all three of its elements continues the repair work in the Japanese American community that started with a government apology in 1988. Healing is a process that, if done right, draws you in and changes you. With the Irei Names Memorial, it also shows how the names — and the people — were all interconnected.

In mid-May when I talked to Williams from Japan where he is visiting family, the team of name translators and cross-checkers were on the last phase of verification.

“We’re seeing the light at the end of the tunnel,” said Williams, a Shin Issei or first-generation Japanese American who lived and worked in the U.S. with visas for 33 years before becoming an American citizen in 2020.

He has another rule called the “camp survivor rule,” which stated that what a survivor wants overrides all.

On records from Rohwer where George Takei was a child of camp, he was listed as Hosato George Takei. At Tule Lake, he was listed as Hozato George Takei. His birth certificate cites Hosato Takei, so Williams contacted the actor, who told him that the origins of his famous name traced back to the reign of King George VI.

Takei’s dad was an Anglophile so fascinated with the British royal family that he started calling his son the regal name. There is something poignant about calling a child a king while he is incarcerated behind barbed wire.

The former “Star Trek” actor asked to be listed in the book of names as George Hosato Takei. Even with a well-known name, there still so much to learn about each individual. Eighty years after the WWII incarceration, agency and power are back in the hands of the powerless.