Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, with daughter Corinne Houston, displays the proclamation presented to her on May 12 by the city of Santa Monica. Her 1973 memoir, “Farewell to Manzanar,” describes the experiences of her family before, during and after WWII. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Author Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston expresses interest

in adapting her work into a movie musical.

By George Toshio Johnston, Senior Editor, Digital & Social Media

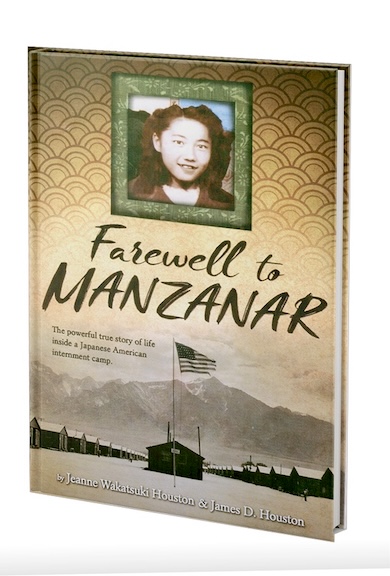

Decades before Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston and her late husband, James D. Houston, completed their landmark book “Farewell to Manzanar,” she spent her early childhood years in the Ocean Park neighborhood of Santa Monica, Calif.

Prior to the outbreak of World War II, the Wakatsuki clan was one of about 400 families with Japanese roots living in the seaside Los Angeles suburb, decades before it became the pricey Silicon Beach hub and liberal bastion with congested traffic.

Houston’s Issei father, Ko, owned and operated a pair of commercial fishing boats, while her Hawaii-born Nisei mother, Riku, kept busy working outside the home while raising a family of 10, with Jeanne being the youngest.

Quotidian existence for Jeanne Wakatsuki was no doubt similar to that of her peers. But her life, not to mention life for her family and for more than 110,000 people living along America’s West Coast with Japanese ancestral ties, went sideways when Japan attacked the U.S. military’s Pearl Harbor naval base in the territory of Hawaii on Dec. 7, 1941, pushing isolationist America into WWII and paving the way for President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 a little more than two months later.

That day of infamy would also, unknown then to Houston, plant the seed of what would become the most-enduring work about how federal government overreach permanently torqued her family forever by sending it to the largest of America’s 10 concentration camps.

By April 1942, the Wakatsuki family was saying hello to Manzanar.

♦♦♦

On May 12, Houston was the guest of honor at the Santa Monica Public Library, which chose “Farewell to Manzanar” as its selection for the 16th Santa Monica Reads, the city’s annual summer reading program.

Houston chooses a question from the audience during the Q&A session at a discussion about her 1973 book, “Farewell to Manzanar.” (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Before reading aloud the proclamation from his city and presenting it to Houston, Santa Monica Mayor Ted Winterer recalled how he had recently been driving on Route 395 with his son and his friend on the way to a spring-break ski trip to Mammoth Mountain.

Noticing the sign for the Manzanar National Historic Site Visitor Center, Winterer said, “We’re coming up to Manzanar. Do you know about it? And one said, ‘Yeah, they made us read “Farewell to Manzanar” in school.’

“The other one said, ‘I just finished it a couple of months ago,’ ” Winterer continued. “So, your legacy is still out there, you’re still informing youth about this horrible episode in American history, and we subsequently had a conversation about today’s challenges, on the issues of looking at peoples’ skin color instead of who they are.”

Next up was Patty Wong, director of library services at the Santa Monica Public Library. Regarding the 45th anniversary of the publication of “Farewell to Manzanar,” she noted how when the book came out in 1973, “This particular moment in our history was not a well-talked-about part of our community, not just only here in Santa Monica but throughout the country.”

Wong added, “Please remember that, not only how important this book was, but how difficult it was, probably, to tell that story and to be part of that period in our history, which was really not that long ago.”

♦♦♦

Houston then took center stage at the library’s Martin Luther King Jr. Auditorium, starting first with a two-part lecture, followed by a Q & A session. The lecture’s first part was about her family’s history and a broad overview of Japanese American history after WWII began, with the second part on how “Farewell to Manzanar” came to be written.

The author corroborated Wong’s observation that writing the book was indeed difficult, with a 30-year gestation, the last year of which was like being in labor for 12 months.

In the decades following the Wakatsuki family’s 1945 departure from Manzanar, Houston noted how in her family, “camp” was never a direct topic of discussion, but something mentioned in passing, usually covered up with a facade of humor.

But in 1971, her college-age nephew visited Houston at her family home in Santa Cruz, Calif. He had heard from a professor about Manzanar, but because of his own parents’ silence on the topic, he knew little of it. He wanted some answers. Houston relayed some superficial stories.

“My nephew looked at me very intently, very quiet, then said, ‘Auntie, that’s bizarre. You were locked up in a prison. How do you feel about that?’ ” Houston recalled.

Her nephew’s simple question was a stick of dynamite in a psychological logjam.

“He asked a question no one had ever asked before, a question I had never dared to ask myself,” Houston said. “How did I feel? For the first time in my life, I dropped the cover of humor and nonchalance and allowed myself to feel, and I began to cry. I couldn’t stop.”

As a result, her nephew’s question inspired Houston to write a family history, just for her large extended network of nieces and nephews, so they could know about where seven of them had been born.

“I was certain none of them knew about their birthplace,” she said. However, it proved to be a job she couldn’t complete. “I found that whenever I tried to write, I broke down and became hysterical and cried uncontrollably.”

Fortunately, Houston had a valuable resource to turn to: her husband, James, who was a creative writing teacher at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Despite Jeanne having been married for 14 years at that point and having known Jim for five years before that, he was as in the dark about his wife’s family’s history as their nephew.

“I had never told him about Manzanar,” she said.

When she did tell him, he told her, “This is not a story just for your family. It’s a story everyone in America should know. Let’s work on this together.”

For the next year, they did, recording Jeanne’s recollections on a tape recorder, interviewing family members and others who had been incarcerated and conducting research at libraries. She found that the months spent delving into the past was “as powerfully therapeutic as years with a psychiatrist — and a lot cheaper.”

On that topic, Houston noted that the situation Japanese American incarcerees faced was similar to the pattern followed years later by Vietnam War vets suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, when feelings held in check might surface 20 or 30 years later, but with the added Japanese cultural overlay of shikata ga nai.

“For many internees, the original shocks of loss, family upheaval and guilt were suppressed for many years,” she said. “I realized the feeling I carried about the incarceration was one of deep humiliation, like a person who had been raped. You are the victim, yet you are sullied by the experience, ashamed to draw attention to it.”

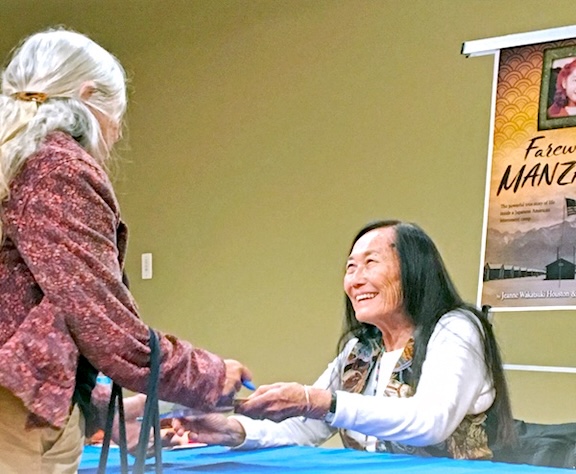

Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston greets an audience member at the post-discussion’s book signing. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Prompted by an audience member’s question, Houston said that more than anything, “Farewell to Manzanar” was a way to come to an understanding of what happened to her father.

“He was destroyed by that experience,” she said. “I watched it happen. I watched him become an alcoholic. He lost his power. In writing the book, I understood what happened to him.”

Another audience member asked Houston how she felt about President Roosevelt.

“My mom and dad lived through the Depression and World War II, and looked at FDR as a hero, as an amazing guy, yet he did this to you and your people. How do you feel about him?” the audience member said.

“I still consider him a hero, Franklin D. Roosevelt,” Houston replied. “I think if you want to name an enemy, it would be Gen. (John L.) DeWitt.”

DeWitt served under Roosevelt as the commander of the Western Defense Command and was infamously quoted as saying: “A Jap’s a Jap. It makes no difference whether the Jap is a citizen or not.”

Houston dismissed him as Gen. DeWitt-less.

The Houstons’ book was published by Houghton Mifflin in 1973 and has been in print ever since, selling steadily as it has become assigned reading for many young Americans beginning in middle and high school. In 1976, it was adapted as a telefilm directed by John Korty, with a stellar cast of Japanese American acting talent. It was nominated for an Emmy and won the Humanitas Prize in 1977.

♦♦♦

Now 83, Houston still keeps pace with her life’s crowning achievement in the literary world, with this visit her first to her former hometown for the purpose of discussing the book.

Asked whether she’d be interested in seeing “Farewell to Manzanar” readapted into a feature film or possibly for a streaming platform, Houston said she would actually like to see it made into a musical.

“I would call it ‘Manzanar USA’ and just do a musical about it, about people in camp, because that’s what we did to entertain ourselves,” Houston said. “It would be about putting on a musical.”

While she has an idea on how she envisions such a production, she said, “I just haven’t thought about whom to send it to. I just haven’t been on it.”

Houston was also asked about the meaning of the title of the book and if there was any irony in calling it “Farewell to Manzanar,” since she has been unable to say farewell, due to its enduring popularity.

“By writing the book and understanding what happened, I was able to say ‘farewell’ to that experience. … Not forget about the experience, but say farewell to the psychological injury that I didn’t even know I had until we wrote the book,” she said.

♦♦♦

Editor’s Note: For more events taking place through June 16 at the Santa Monica Public Library inspired by the choice of “Farewell to Manzanar” as this year’s Santa Monica Reads selection, visit tinyurl.com/y7v4vn3x.