The Ikeda family opens up about their personal recollections of wartime incarceration in Canada — and the silence and stigmas associated with it — during and after World War II.

By Diana Morita Cole, Contributor

(Originally published in the Dec. 16, 2016-Jan. 26, 2017 Holiday Issue of Pacific Citizen.)

JACL passed a resolution at its 47th National Convention in July to recognize the violation of civil rights that Canadian citizens of Japanese descent suffered at the hands of their government throughout World War II and for three and a half years following the formal surender of Japan. The resolution was sponsored by the organization’s Philadelphia Chapter and its president, Scott Nakamura.

This holiday season is a season to remember, a time to make sense of our personal and collective histories. For remembering can build a connection between our now and then, creating a vital link to those areas of psychological neglect, too often kept buried from ourselves and our children.

Indeed, the theme of hushed silence and hidden memories is crucial to the understanding of the story of the 22,000 Japanese Canadians who were torn from their homes and expelled from the Pacific coast during World War II.

Joy Kogawa, a renowned Canadian writer, expressed this theme of silence and forgetting in the poetic opening to her 1981 novel “Obasan”:

I hate the stillness. I hate the stone. I hate the sealed vault with its cold icon …

Unless the stone bursts with telling, unless the seed flowers with speech, there is in my life no living word.

In 1945, after the end of the war, Japanese Canadians were ordered to leave British Columbia. They could accept the proceeds from the sale of their properties and receive free passage to Japan in exchange for their citizenship. Or, they could receive train fare and a paltry allowance to move east of the Rockies. Unlike in the United States where ethnic communities were established in various cities, in Canada, Nikkei families were consigned to live in isolation of one another, in small towns and on farms where there were labor shortages to fill.

The racism they continued to face from white society fostered both silence and forgetting. Today, more than half a century later, few talk willingly about what happened.

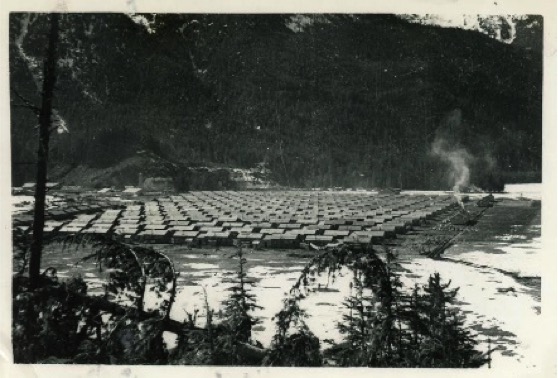

Held in remote, mountainous ghost towns where they starved and sometimes died and also deprived of the support of their fathers and sons who were sent away to slave in work camps, Japanese Canadians were fleeced of their vast holdings in the Lower Mainland and forced to pay for their own imprisonment.

Far too many of their descendants report that they were never told by their elders or teachers in school about the inordinate cruelty foisted upon their families by their own government.

By 1944, when it became clear that Japanese American citizens in the U.S. could no longer be deprived of their freedom of movement, in Canada, Prime Minister William Lyon MacKenzie King and his Liberal Party became alarmed at the prospect of Japanese Canadians returning to the coast to claim what was once their homes and property.

Using the authority of the National Emergency Transitional Powers Act, King embarked on a policy of deportation and yet another expulsion of the Nikkei to the provinces east of the Rockies.

Beginning in May 1946, the Canadian government stripped 3,964 Japanese Canadians of their citizenship and banished them to Japan in accordance with a policy benignly called “repatriation,” which belied the fact that two-thirds of the deportees were born in Canada and had never seen Japan.

The inability of many Japanese Canadians who endured these atrocities to fully acknowledge the scope and depth of the injuries and injustices imposed upon them served as a signal, a bellwether to what had seriously gone awry in this British colonial empire, this place called the Dominion of Canada.

Mark Kunji Ikeda in “Sansei: The Storyteller.”

Mark Kunji Ikeda explodes across this cultural abyss of denial to present his creative response to his family’s disjunctive history with his award-winning drama “Sansei: The Storyteller.”

Combining narrative and dance, Ikeda tells of his family’s past, including his grandparents’ emigration from Japan to British Columbia, where his grandfather, Yoshinori Ikeda, became a successful fisherman, owning 17 lots, three houses and several fishing boats in Steveston, B.C.

These interesting and delightful vignettes provide a vivid context for the stories Ikeda then conveys about his family’s incarceration and the labor men were forced to perform, logging forests and building roads for slave wages.

In one story, Ikeda’s uncle, Ed Ikeda, who was 3 years old when his family was displaced to Rosebery, finds a hummingbird and wants to make a pet of it. As Ed Ikeda explained, “We were sent away, we were living in this house, and it was sort of a camp. I don’t know how, but I found this hummingbird, I’m sure I didn’t catch it. So, I must have somehow got it, maybe it was not well, and I put it in my shirt pocket. Of course, I was all excited, and I ran home to show my mother, but I guess running home in my shirt pocket … maybe it was sick, I don’t know, but I never did find it again.”

In a recent telephone interview, Ikeda’s father, Fred, who was born in Alberta in 1950, reported that he never heard the story about his brother’s pet hummingbird until when he saw it performed live by his son — some 50 years later. He said he broke down and cried.

The absence of a cohesive family narrative, of seldom bearing witness to the saga of what their parents, grandparents and older siblings suffered, is evidence of the cultural oppression that continues far beyond the apology of 1988. This self-denial is a chilling reminder of the psychological isolation that exists within the vast geography of the Canadian landscape and psyche of its inhabitants.

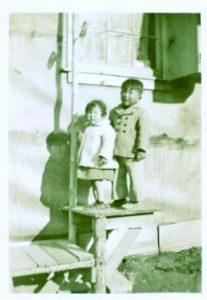

Jane and Ed Ikeda at Tashme.

Jane Ikeda Hayes, Fred Ikeda’s older sister, was born in May 1941, just a short time before her family was ordered to Hastings Park. In a recent conversation, she confided, “I’ve never read those books, like ‘Obasan,’ because I don’t want to acknowledge I’m Japanese. I wanted to obliterate my background by living in denial. If I could have woken up blonde and blue-eyed for a week, I would have been glad to die. We’re driven by past hurts but live in the present.”

But, Hayes went on to say, “I do remember being happy in New Denver. I thought it was normal for the walls in a house to buckle.”

Prime Minister King issued his Orders-in-Council under the War Measures Act on Feb. 24, 1942, to “remove all persons of Japanese origin from the coast.” Shortly after, Hayes, her parents and her older brother, Ed, were confined to an animal barn in Hastings Park.

People were herded and divided, like cattle — dispersed to separate containment areas (men in one building and women and children in another) and barred from eating together as families. Reports of guards beating female captives for daring to step outside their stalls have been recorded by Mona Oikawa in her 2012 book “Cartographies of Violence.”

After Hastings Park, Hayes and Ed Ikeda, along with their mother, Itsuko Okimura Ikeda, were forcibly removed to Rosebery, a prison camp in the Kootenays outside New Denver. Their father, Yoshinori Ikeda, like many able-bodied Japanese Canadian males, was exiled to live and work in a road camp. In his case, he was sent to build the Hope-Princeton Highway.

Ed Ikeda says he never saw his father again until after the war, when his family was moved to Alberta in 1945. But Hayes suspects Yoshinori Ikeda did return intermittently to the next prison camp they were held in, which was Tashme, near Hope, B.C. “How else would I remember the white drawstring bag filled with copper nickels?” she asked.

Ed Ikeda also recalled in some detail his family’s detention at Tashme — a site built far away from the other nine prison camps for the families of the men working on the Hope-Princeton Highway.

“The conditions were brutal. There was no insulation, and we were living in a duplex, with an open ceiling where we could hear what was going on next door. There was no privacy,” he said.

He also remembers a wooden bath and his mother receiving a jar, at regular intervals, filled with coins — the paltry wages his father earned by building BC Hwy 3. “I have a picture of my father working on the highway,” he recalled. “There was a machine, but the crews only used pick-axes, shovels and wheelbarrows.”

Ed Ikeda remembers receiving food in a box but doesn’t know if that was the regular delivery system. “There were boxes of spam, rice and oranges wrapped in tissue paper that I used to make parachutes to throw from the top of a pile of railroad ties,” he said.

Official reports indicate that relatives in war-torn Japan often shipped food items to their relatives in Canada because the government had frozen the bank accounts of the Japanese Canadians. Denied access to their savings, the captive Nikkei were still expected to pay for their own food, blankets, clothing and building supplies from the small monthly allowance they received.

The three members of the Ikeda family were eventually displaced from Tashme to New Denver.

Ed Ikeda remembers living close to a mountain and discovering iron pyrite, which he believed was gold. His mother tried growing tomatoes to make ketchup — “We didn’t have any then!” — and remembers going down to Slocan Lake to gather up ice for making ice cream. “My mother never complained,” he said. “She was a capable woman. She sewed my pants, shirts and knitted.”

Like Itsuko Ikeda, Nikkei women became the mainstays of their broken, detained families after their husbands were whisked away to labor camps. Any man who begged to remain with his family was sent even further away to one of the POW camps in Ontario, where he was forced to wear a uniform with an orange target painted on his back.

After the war ended in 1945, the entire Yoshinori Ikeda family was displaced again — east of the Rockies. They moved to Picture Butte, Alberta, where Douglas Ikeda, Yoshinori’s brother, owned a construction company. The reunited family of four lived in a chicken coop, hauling water from a cistern before Douglas Ikeda was able to find them a suitable house to rent.

“My father was a stranger,” Ed Ikeda recalled. “I hadn’t seen him until the family moved to Alberta. He worked with my uncle to build houses.”

Fred Ikeda, Ed’s youngest sibling, was born in Lethbridge, Alberta, in 1950. When asked about his birthplace, Fred Ikeda said he has no idea why his birth certificate says he was born in Lethbridge, when his family was living in Picture Butte at the time. According to his sister, Jane Ikeda Hayes, Lethbridge had the only hospital in the area. “Picture Butte was just a bunch of sugar beet farms,” she said.

A year later in 1951, Yoshinori moved his family back to Vancouver, B.C., where they all took temporary lodging at the Roosevelt Hotel and then at a boarding house on Alexander Street for about four months. Ed Ikeda recalled, “My father bought a house at 5492 Killarney. It had cherry trees and apple trees. The fruit from the trees was delicious!” But Ed Ikeda’s mother was embarrassed because she thought her husband could have bought a better house.

Hayes remembers her family living in a very small house with a lean-to on Killarney Street. “There wasn’t room enough for me in the house,” she said. So she slept alone in the lean-to, which was damp and covered with black mold.

During this time, Ed Ikeda’s father worked as a handyman for Dr. Ballard at his home. “We were dirt-poor,” Ed Ikeda said. “I don’t know how my father managed to give me 25 cents a week for allowance. That was a princely sum back then.”

Hayes recalls her father working as a janitor for the Niagara Hotel until he was 83 years old. Their mother worked in a shop on Alma Street, sewing wedding dresses, just as she had when she returned to Canada after caring for her grandmother in Hiroshima before the war.

“I was never close to my father,” Ed Ikeda said. “We didn’t know each other. He never talked about himself or the hardship he had to endure.” Ed Ikeda also explained that his younger brother Fred, Mark Ikeda’s father, wouldn’t know much about the internment because he was born well after the war had ended.

“I never heard any stories about the internment because my family blocked it out,” Fred Ikeda said.

It is this gauze of silence, this generational absence of memory that Mark Ikeda’s drama “Sansei: The Storyteller” rips open, bringing tears of awe to members of the audience when they hear the hum of the hummingbird’s wings, carrying them into a story of remembering the past.

As harsh as they are, these stories must be respected if the atrocities of the past are to be prevented from happening once again.

“Imagine, walking through the archway into the holding facility in the Hastings Street horse barns, or at camp, or a POW camp in Ontario,” Mark Ikeda said. “When we arrive in the camp, someone says, ‘When we enter this gate, we shall never be allowed to leave again until the war is over.’

“Let’s remember this feeling,” Mark Ikeda continued. “And remember, not one Canadian law was broken.”