Linda Taira with the plaques, placed on a small boulder by members of the Italian volunteer group Toscana 44 honoring the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the 36th Division, the 100th Battalion and her uncle, Pvt. Masaru Taira (Photo: Courtesy of Linda Taira)

In Linda Taira’s quest to learn more about her uncle, help comes from an unexpected source.

By George Toshio Johnston, Senior Editor

Here is what we know about Masaru Taira.

Pvt. Masaru Taira (Photo: Courtesy of Linda Taira)

A Nisei, he was born in the territory of Hawaii to Kame and Kamado Taira, who emigrated there from Okinawa Prefecture in 1907. Masaru had 12 siblings, 11 of whom reached adulthood. (His parents went on to found the Pacific Bakery in Honolulu — completely unrelated to that other Taira family, also from Hawaii, that operates King’s Hawaiian Bakery and Restaurant in Torrance, Calif., which is part of the ubersuccessful Irresistible Foods Group.)

After Japan’s Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor and after the United States joined what would become known as World War II, following his older brother, Wilfred, Masaru Taira enlisted in the Army, joining several of his high school classmates. Like thousands of his fellow Nisei from Hawaii and the U.S. mainland, Taira was placed in the segregated 100th Battalion/442nd Regimental Combat Team and went through basic training at Camp Shelby, Miss.

Later, after getting assigned to L Co., his cohort and he were shipped to Europe to fight for the Allies with their fellow Americans. In the Tuscany region of Italy, Taira and his comrades in arms got their orders: relieve the 100th Battalion and take Hill 140. Take it they did, over the course of a grueling five-day battle, from July 3-7. It would prove to be one of the bloodiest battles of the Italian Campaign. But that was something the 19-year-old would never know.

Pvt. Masaru Taira was killed in action on July 4, 1944. He was 19.

❖❖❖

Linda Taira addresses those gathered in a room at the JACCC to hear her tell the story of her search to find Hill 140 in Italy’s Tuscany region, where her uncle, Pvt. Masaru Taira, was killed during WWII. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

If one is old enough, the name Linda Taira may sound familiar. A Tokyo-born award-winning TV journalist, she was first seen professionally years ago at the local level in Hawaii, on Seattle’s KING TV and then on CNN and CBS, doing standups in front of iconic locations like the U.S. Capitol. After leaving journalism, she worked in public relations, including stints at PBS and the Boeing Co. Now, she operates her own company, Taira-Welch Communications.

As for her Japanese American community bona fides, Taira serves on the board of directors of the Japanese American Cultural and Community Center in Little Tokyo and, in 2015, she was among those selected to be a part of the Japanese American Leadership Delegation. There are also her parents: her late father (and Masaru’s younger brother) Walter Taira, who himself served in the military during the Korean War, where he was awarded a Purple Heart after being severely wounded and who later also served in Vietnam; and her mother, Hisako, now 95, originally from Tokyo. (Walter Taira was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 2010 and would also in 2022 be posthumously awarded the Ambassador for Peace medal from the South Korean government.)

Other JA Veterans news: Keeping the Aloha Spirit Alive (Nov. 1, 2024)

Other JA Veterans news: BBC to Tell 442 Saga as a Podcast (Nov. 1, 2024)

Other JA Veterans news: JA Vietnam Vets Get Their Close-Up (Nov. 1, 2024)

But decades before her professional career began, going back to her childhood, she had heard family stories about an uncle who died during WWII. That uncle was, of course, Masaru Taira. “All I knew was, I heard he was killed in action in Italy in WWII,” said Taira. “And then I was so shocked later on, as I grew older — I found out he died on July 4, 1944.”

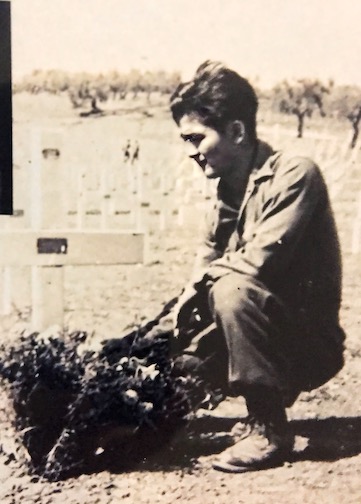

Wilfred Taira visits the Follonica, Italy, gravesite of his younger brother, Masaru Taira, who was killed in action on July 4, 1944. (Photo: Courtesy of Linda Taira)

Masaru Taira’s death was a devastating blow to her grandparents and his siblings. For older brother Wilfred Taira, a Silver Star winner, Masaru’s death was a topic of which he would say almost nothing. “There are stories, but I can never confirm it, that his brother, a medic, was there and saw his brother die,” Linda Taira said.

As the years passed, those stories about her uncle stayed with her. It would take years, decades, for the pieces to fall into place such that she could pay her respects to an uncle she could never know in person.

On May 18, following the biannual Spit and Polish of Little Tokyo’s Japanese American National War Memorial Court, organized by the Veterans Memorial Court Alliance, Taira, at the invitation of VMCA board member Les Higa, gave a presentation to young people not too far removed from the age Masaru Taira was when he was killed. Three weeks earlier, she told them, she had been in Italy, where she visited the site where he fell.

It was the culmination, Taira told the assembled young adults, of her more than 40-year-old idea to someday, somehow, honor his memory. It was, she told the Pacific Citizen, destiny — but when it happens, destiny works to a timeline that no mortal may hope to know or understand.

❖❖❖

Like many, Linda Taira had begun to grow alarmed at the backlash against the Black Lives Matter movement and, more specifically, the May 2020 killing of George Floyd, plus the spike in anti-Asian violence that accompanied the Covid-19 pandemic. “I remember that sense of the country at that time and the racism coming back,” she told Pacific Citizen. “It was the first time I really started thinking, I think I have a story that I want to tell.” That story, of course, was about her uncle and his selfless service to the nation that had incarcerated fellow Japanese Americans living on the mainland’s West Coast.

There were, however, obstacles to Taira’s quest that had to be overcome.

Masaru Taira, in uniform, at Camp Shelby, Miss. (Photo: Courtesy of Linda Taira)

“As I looked more at what I had, I realized I needed to fill in a lot of gaps in my own knowledge,” Taira said. Unfortunately, most of the people who could have told her more details about Masaru Taira had all passed away.

Nevertheless, Linda Taira began doing more detailed research, and among the tools she had were a trove of letters Masaru Taira had written to his sundry siblings.

“Masaru was a prolific letter writer,” Taira said. “I have all the letters he wrote from the time he left Hawaii for Camp Shelby, at Camp Shelby, and a few letters he wrote from Italy.” He wrote to his many brothers and sisters. With each one, she said Masaru “opened up a different dimension of his personality.”

“And so, I was able to get a lot of color of what was going on in his mind, and some were a little bit more about what was going on in basic training, and some of it was more about what he was thinking.”

In the July 4, 2021, edition of USA Today, she was able express her thoughts about the meaning of her uncle’s abbreviated life in an opinion piece.

Meantime, there was another development in her research that would lead her to the spot where her uncle lost his life: Facebook.

❖❖❖

For all the criticism social media has received in recent years, be it the spread of misinformation, lies and hate, damage to young people’s self-esteem, creating unrealistic and unhealthy aspirations and expectations of success and wealth — there are also legitimate, aboveboard examples where social media has played a role in disseminating useful information, giving voice to the disenfranchised, shining light on issues that might otherwise go unnoticed or connecting far-flung people with specific interests.

A member of Toscana 44, wearing a period U.S. Army uniform, raises a 48-star U.S. flag. (Photo: Courtesy of Linda Taira)

For Taira, it was the latter examples than proved to be an unexpected but critical boon for her journey. In her internet research about her uncle, Facebook proved to be a game-changer.

Taira said, “I think Facebook knows your algorithm, so they knew I was interested. I kept coming up with this group, and their name is Toscana 44. In Italian, Toscana means Tuscany, 44 means 1944, so I started following their page.

“They’re a group of young guys. They’re in their 20s and 30s, and they are interested in the Italian Campaign, which is World War II, as it was fought in Italy, from South to North.”

Yes, thanks to Facebook and members of Toscana 44 — all of whom are fascinated by the story of the 442 — Linda Taira had found the key to helping her unlock how she would visit the site where Masaru Taira was killed in 1944.

❖❖❖

Although the saying “timing is everything” is usually applied to standup comedians, it was equally apropos to Linda Taira’s quest. In this case, it was the intersection of her concerns about living this fraught time in American society, her personal interest to learn more about her uncle and living in a time when a vehicle like Facebook allowed her to connect with others in a different continent who also had a similar interest, namely what happened during WWII in the Tuscany region of Italy.

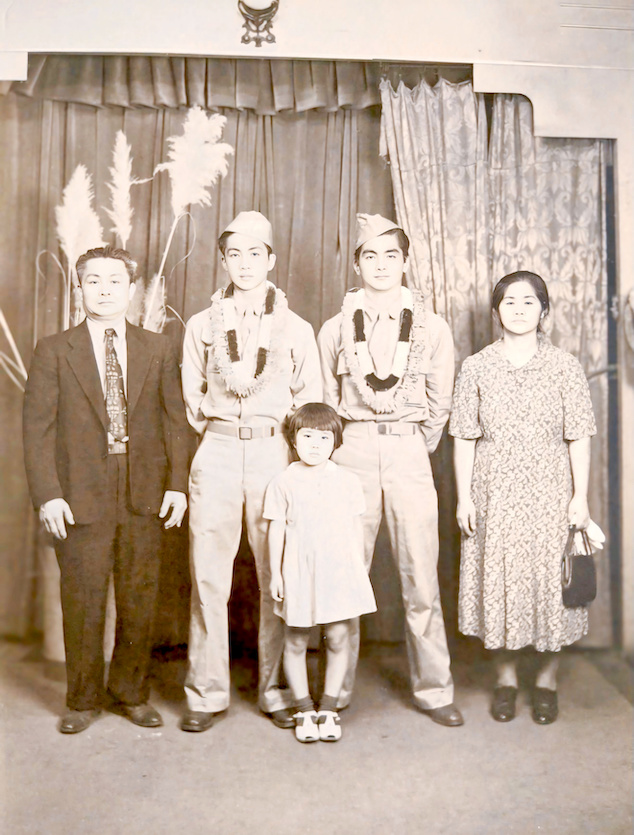

This studio photo of brothers Masaru and Wilfred Taira, flanked by their parents, with youngest sister, Blanche, was hurriedly arranged before the brothers shipped out to Camp Shelby. “This photo was in the family butsudan for as long as I can remember,” Linda Taira said. “I think seeing the family photo — with all its pain and poignancy — every time I went to my grandparents’ house piqued my curiosity. I never found out much about it, until years later after many family members were gone. I felt driven to find out what happened to Masaru and piece together his story, eventually leading me 80 years after his death to visit where he was killed in Italy.” (Photo: Courtesy of Linda Taira)

“I think the stars aligned perfectly for me to understand with all the years of family history, but also with where we are and were at the time, I started looking into this as a nation and really getting a sense of appreciation,” Taira told the Pacific Citizen. “And in some ways, I had to wait for these young men in Italy to reach an age when they were able to help set the stage at Hill 140 so that others like me could actually visit and walk.”

One of the obstacles Taira would have faced that the men of Toscana 44 had already overcome: Hill 140 is privately owned. Fortunately, the owner allows Toscana 44 members to access the property and the hill. “Without them, I could not have even known where to go,” she said. She was also the first family member of someone who was killed there to visit the site — and they were always curious about the men who were killed in combat.

A closeup of the plaques placed by Toscana 44 (Photo: Courtesy of Linda Taira)

Upon reaching the vicinity of where it was believed Masaru Taira fell, the members of Toscana 44 had a surprise for their American visitor: a pair of metal plaques embedded into a small boulder. One dedicated to the memory “of those who fought to free this place,” with the liberty torch emblem of the 442nd RCT, the Red Bull insignia of the 34th Infantry Division and the original coat of arms of the 100th Battalion, and one more honoring Masaru Taira.

❖❖❖

Having now achieved her goal of making a pilgrimage to the location where Pvt. Masaru Taira was killed, Linda Taira can reflect on that journey. For her, to stand at the top of Hill 140 and observe a moment of silence for him was the pinnacle of what she had sought. “I didn’t even know that someday that would even be possible,” she said. Although improbable and decades in the making, Linda Taira’s journey to find and visit where Pvt. Masaru Taira fell turned out to be possible after all.