Abe, Cheung Are Back With New Collection of Personal Perspectives.

By Gil Asakawa, P.C. Contributor

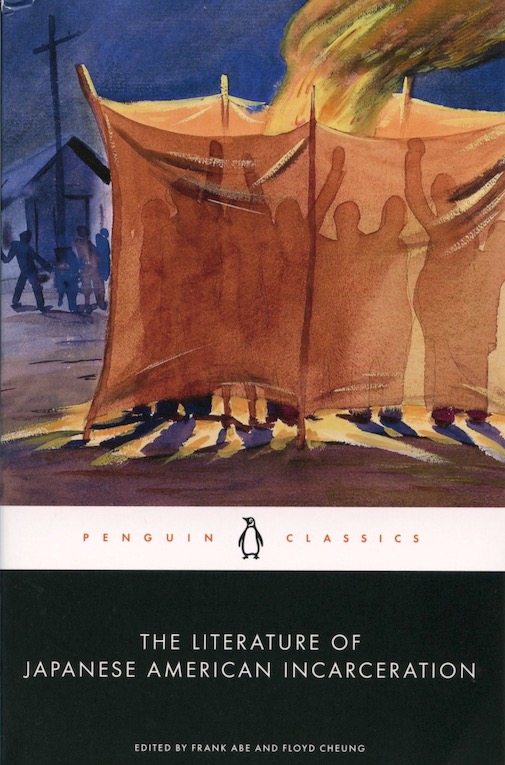

“The Literature of Japanese American Incarceration,” a new book, tells the story of Japanese American experience in a format that allows the voices of JAs to share their stories from their point of view. It collects the written record of the community in excerpts of both fiction and nonfiction books, journals, letters, diary entries, poetry and song lyrics by Japanese Americans, as well as the text of government documents (including Executive Order 9066, which led to the imprisonment of over 120,000 people of Japanese descent).

The book also presents these passages in a chronological timeline from prewar to wartime, from postwar to the redress campaign. And it ends with a focus on how the JA experience still echoes today in the divisive politics over race and immigration.

The book also presents these passages in a chronological timeline from prewar to wartime, from postwar to the redress campaign. And it ends with a focus on how the JA experience still echoes today in the divisive politics over race and immigration.

Abe is a well-known author and activist who organized the first “Day of Remembrance” event in 1978 with writer Frank Chin, and with filmmaker Sharon Gee produced the award-winning PBS documentary “Conscience and the Constitution,” the definitive chronicle of the wartime draft resisters incarcerated at Heart Mountain. He also was lead author of the award-winning graphic novel “We Hereby Refuse” (See July 2, 2021 Pacific Citizen, tinyurl.com/4u39a24j), and co-edited the American Book Award-winning “John Okada: The Life & Rediscovered Work of the Author of No-No Boy,” with Greg Robinson and Floyd Cheung. (See Feb. 22, 2019 Pacific Citizen, tinyurl.com/yp5955k6)

Cheung is a literary scholar and professor of Asian American Studies at Smith College who has edited, collaborated and co-authored a handful of books including “The Hanging on Union Square” and “Recovered Legacies: Authority And Identity In Early Asian American Literature.”

The duo were familiar with so many books, articles and collections between them that they felt there was enough material to compile into a first look at the diversity of experiences and talent of storytelling. Cheung is quick to credit Abe, who’s been following everything related to JA incarceration for decades.

“I teach a class at Smith on Japanese American experience in the camps before, during and after, and I used to put together a reader for that,” said Cheung, who’s been teaching for 25 years. “And, of course, Frank’s, you know, 45 years of experience collecting.”

The pair knew the source material was there. And Elda Rotor, a vice president for Penguin Classics, who is Filipino American, had decided that she wanted to diversify the Penguin Classics and include more Asian American texts.

She reached out to Cheung after Penguin published H.T. Tsiang’s “The Hanging on Union Square,” which Cheung edited, about ideas for a next project. He proposed a book-length version of his class reader list, and Abe was the easy choice to collaborate with. “Frank and I got to know each other by working on the John Okada book,” Cheung said.

By organizing the volume in chronological order from prewar to today, adds Abe, the book is a narrative account. “You can get a sense of what it felt like to live through the experience, moment to moment,” he said. “So, for educators, teachers or students, you can see the progression of insults that the government perpetrated on the people in sequence and how each event builds on the one previous, leading to the most extreme expression of government, or incarceration, which is too late.”

And although the chapters organized under sections for “Before Camp,” “The Camps” and “After Camp,” titled “Arrival and Community,” “Arrest and Alien Internment,” “Fairgrounds and Racetracks,” “Deserts and Swamps,” “Registration and Segregation,” “Resettlement and Reconnection” to, at the end, “Repeating History,” an epic story, each chapter is made up of brief passages, almost like historical snapshots so readers can absorb the scope of the history in digestible bites. But Abe cautions that the book shouldn’t be treated like a mere literary snack, because it offers a lot of food for thought. “It’s not just snapshots, but cries of anguish, pain, cries of anger,” he noted.

Some of that anger might be directed at the words of Mike Masaoka, a leader in JACL and a prominent proponent of JAs acceding to the government’s orders to prove their patriotism. His words are cited in the book.

For some readers, who may be familiar with the broad strokes of Japanese American history and the incarceration experience, a collection of stories about that history might seem pedestrian. But if your family experienced incarceration or still feel the effects of generational trauma inflicted by those years, the voices that leap out of the pages will be strikingly fresh and emotional wrenching. For an outsider who hasn’t lived through it but knows about it intellectually, reading the first-hand accounts or the fictional excerpt curated by Abe and Cheung bring a force of immediacy to the history.

“We’d like to say that it’s the collective voice of the people who are incarcerated, that although the authors in the collection have wildly different backgrounds and experiences, there is a commonality, a collective sensibility that emerges from the people who’ve been targeted, for one reason and one reason only, their race which they shared with the enemy, wartime enemy,” Abe emphasized.

The toughest part of assembling the book was deciding what not to include.

“I mean, we started off with way too many selections,” admitted Cheung. “And we started, wanting to preserve the integrity of longer pieces whenever we could. Eventually, we submitted a version that was maybe twice as long. And we gave it to the editor. And she said, ‘You got to cut it by about half.’ ”

Cheung and Abe eliminated pieces they would have liked to keep, and chose to edit down some other passages to shorter excerpt while still keeping the story and messages intact. “In order to maximize the diversity, and yet keep the collective voice and arc, we did that by perhaps selecting smaller selections of longer pieces in order to preserve that particular voice as part of the tapestry.”

A striking aspect of that diverse tapestry is the number of entries in the book that were translated from Japanese, taken either from Japanese publications, or, in some cases, a Japanese literary magazines that had been published in camp. The book doesn’t reprint excerpts of “the greatest hits of JA literature” like “ Farewell to Manzanar,” which most JAs are already familiar with.

The goal, Abe explained, was to “recover pieces that have been long overlooked on the shelf, buried in the archives, or languished unread in the Japanese language. And the number of new translations we have from the Japanese that we do present, I think testifies to one of the long-term effects of the camps, which is the loss of language and culture, due to regulation, suppression, and the ongoing stigma of acknowledging any affinity to Japan after the war. This is why I don’t speak Japanese or read Japanese.”

Because there’s still so many stories to uncover and share, and with so much that may be still untranslated in Japanese, there could easily be future volumes of this book. But it won’t be Abe or Cheung compiling the stories. Cheung thinks maybe his students might tackle the project.

Abe said, “There is a volume two, and there’s volume three and volume four, there are 120,000 ways to present the literature of incarceration. This is just one way to slice it. And what we’ve selected are not necessarily the best 68, you know, selections of Japanese American across recent literature. But they point to the diversity and range of expression from each of these writers, and other writers, whose voices, for example, are still very locked up in Japanese. So yes, much more work needs to be done.”

One definite addition that Abe and Cheung can confirm, is that there was an audiobook version that was released May 14 at the same time as the paperback and is read by some notable Japanese American actors and artists, including Greg Watanabe (who played Mike Masaoka in “Allegiance”), Keone Young (“Deadwood”), and Tracy Kato-Kiriyama (who’ll be reading among other pieces, her own poem, which is included in the book). Ren Hanami sings a lyric from the book, that was written to be sung to a traditional Japanese song. Abe himself was asked to read the introduction and the afterword.

This article was made possible by the Harry K. Honda Memorial Journalism Fund, which was established by JACL Redress Strategist Grant Ujifusa.