Vincent Chin has been with author Paula Yoo for over half of her life. (Photo: Jarod Lew)

Stories are the shape of our existence. On the 40th Anniversary of his death, three AAPI artists and storytellers carry on Chin’s legacy.

By Lynda Lin Grigsby, Contributor

A love letter is a blank canvas on which emotions are painted. For his latest commissioned piece, a portrait to commemorate the legacy of Vincent Chin, the artist Anthony Lee received little direction.

Lee was told to paint a version of the ubiquitous black-and-white picture of the fresh-faced man smiling with the bouffant hairdo. Inspiration was limited because Chin died at 27 years old before camera phones made it possible to document every moment of life.

Artist Anthony Lee took the portrait of Vincent Chin to the June 25 Unity March in Washington, D.C.

Still, Lee picked up a brush and started pushing paint across the canvas. The artist laid his feelings bare in the portrait of the man he never met but heard about in whispers in his native Detroit, where Chin was killed 40 years ago.

While painting the contours of Chin’s face, Lee saw himself, a Chinese American Cantonese-speaking man on the precipice of marriage. The artist composed his love letter — an altar scene with tufts of incense smoke that look like they could lift off the canvas and dance into nostrils.

“I want for the record to be known that even 40 years later, we still see him,” said Lee, 30.

In Chinese culture, food offerings are gestures of enduring love. Chin is a part of every Asian American’s family tree ever since his last words, “It’s not fair,” became a rallying cry of a movement. Chin is a part of your history, his real-life cousin Annie Tan implied as she stood by his gravesite at Detroit’s Forest Lawn Cemetery last month and called him “our cousin Vincent.”

Chin may have come into your life in a college Asian American Studies course or through Renee Tajima-Peña’s seminal documentary (see related story here), or in the fiery words of the founding members of the American Citizens for Justice, but he has always been there waiting for you to awaken. The altar is a perpetual prayer for Chin. On the 40th anniversary of his death, the message is clear: Asian American Pacific Islanders need to tell their stories until they metabolize into the American diet.

Telling our stories means reclaiming our humanity, said Helen Zia, ACJ founding member, during the commemorative event in Detroit. Through different mediums, three AAPI artists seek to fill in the blanks of Chin’s life and legacy. This is their love letter to Vincent Chin.

Honor the Words

“I’m happy to be the cranky Korean auntie,” says author Paula Yoo. (Photo: Sonya Sones)

More than anything, Paula Yoo wants her readers to see Chin, the person who loved books (“Historical fiction was his jam.”), football and fishing. In 1982, he had just started a job as a draftsman at a small engineering firm, a respectable career for the son of immigrants who wanted to set down roots with his love, Vikki Wong.

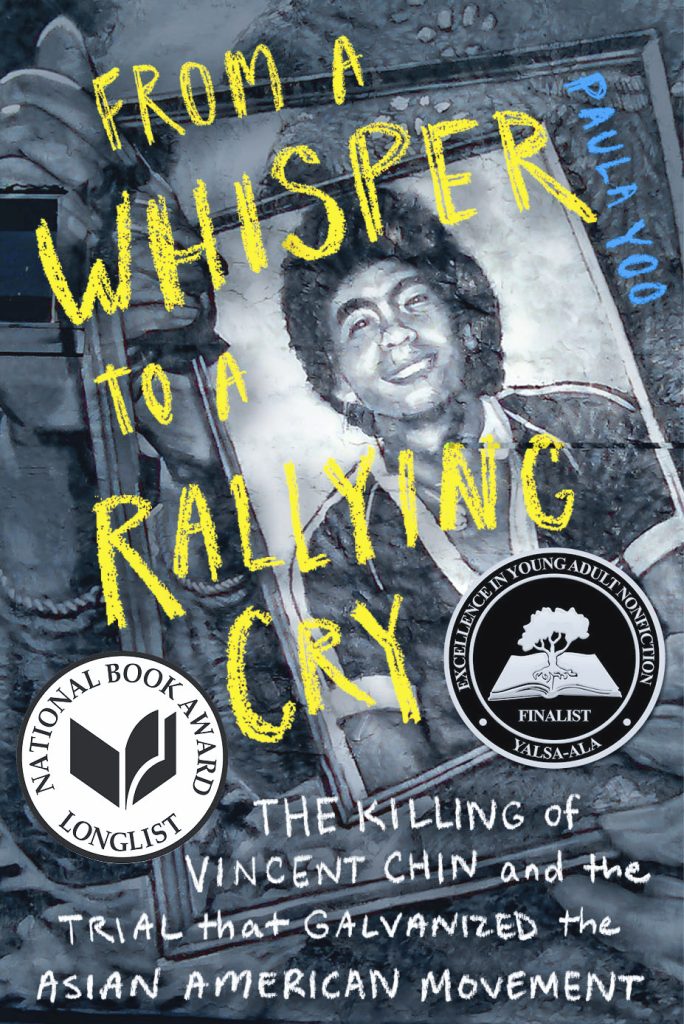

But deep down beat the heart of an aspiring writer, who wrote a poem he called “Vikki.” For any writer, getting published is a dream, so Yoo printed Chin’s poem in her 2021 book “From a Whisper to a Rallying Cry,” turning Chin from a beloved son, victim and symbol to a published poet.

So stay with me

And we’ll face the tomorrows

To find if our love

Can overcome the sorrows

Remember me always.

“It’s incredibly prescient,” said Yoo about Chin’s poem. “We have to honor those words and make sure that there is a tomorrow for his legacy.”

For most of her life, Chin has been whispering to the author to tell his story — remember me always. In 1993, with a fresh master’s degree in journalism from Columbia University, Yoo started a job at the Detroit News. Initial feelings of pride and excitement eventually gave way to nervousness. After all, this was the same city where Chin was killed. Would a Korean American woman who drives a Nissan be safe?

The 2021 book about Vincent Chin by Paula Yoo is written for young adults.

It’s a question Lee said the AAPI community in Detroit reckoned with after Chin’s white assailants were sentenced to probation and acquitted in the civil rights case. Old Chinatown, whose spirit once pulsed with life, started fading when its people left for the suburbs.

“There’s no wonder why Asian people don’t really go there because Asians want to be where there’s security,” said Lee. “It was just a big pill the whole Asian community had to just take.”

Lee is a mural artist who, during our Zoom meeting, twirled a naked paintbrush around his finger. He was lured by the blank canvases of the dilapidated building in Detroit’s old Chinatown. He wanted to inject beauty into a place that time and people left behind.

He lowers his voice to affect his inner idealistic self. “I wanted to be the change. I want to bring back Chinatown. I want to make things beautiful.”

The answer was always no. And it becomes clear that the community was arrested in trauma that still bubbles to the surface 40 years later when people are called on to speak about Chin — voices tremble and tears spring from eyes like the wounds of injustice are still fresh.

Chin’s death made him a symbol of a movement that unified AAPIs against racism and xenophobia. But when a person’s image becomes a symbol, their tragic death defines their life — think Emmett Till’s open casket or the police officer kneeling on the back of George Floyd.

In contrast, Yoo likes to look at the emotional journey of a character she writes. The subjects of her books are diverse — Olympic diver Sammy Lee and groundbreaking actress Anna May Wong — but her choice for a target audience is unwavering.

Yoo writes for children and young adult books about heavy issues in an age-appropriate and unflinching style of a journalist who injects the reader into the complexities of all the characters, including the killer with the baseball bat.

To write the book intended for high school-age kids, Yoo does not shy away from the violence or its stark fallout. On Zoom, Yoo, 53, holds up a dictionary-sized binder filled with court transcripts that dissected the circumstances of Chin’s death. It drops to the floor with a loud thud.

“That’s how you really understand how horrific racism is,” said Yoo. “What did we lose here?”

Chin, who loved to read, could have been the next great American author, but we will never know for sure. For now, according to his words, we can only see if our love can overcome sorrow.

Giving Visuals to Data Points

Wearing a bright red blazer against the dark backdrop of a Detroit theater, Zia sighed.

“Here we go again,” she said to the audience about the parallels of the present-day to the atmosphere that led up to Chin’s death 40 years ago. When the pandemic shut the world down and anti-Asian hate crimes skyrocketed, community leaders started intoning Chin’s name again. Now, just like then, AAPIs are being scapegoated, attacked and killed. But for years, there was only one documentary to reference, “Who Killed Vincent Chin?” from 1987.

Now there are two.

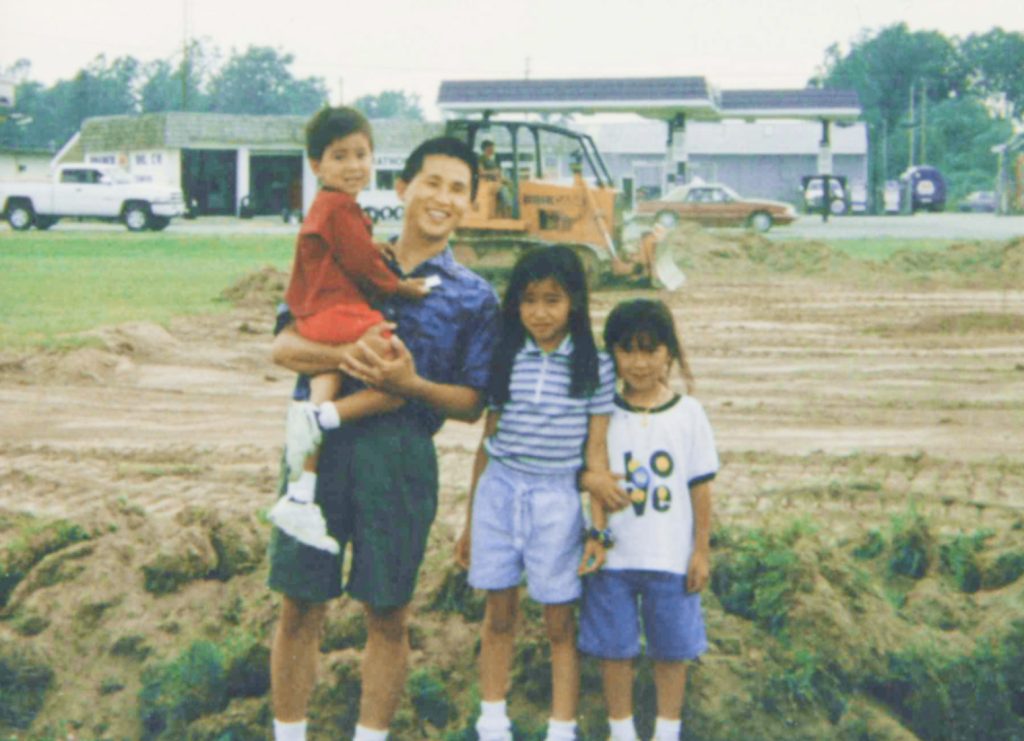

Patriarch Chun Siev is a Cambodian refugee who escaped the genocide of the Killing Fields and achieved the American Dream in the city of Bad Axe, Mich.

“Bad Axe” is a new documentary about one AAPI family’s struggle to run their restaurant in the rural city of Bad Axe, Mich., amid pandemic closures, political divide and fear of safety so deep that in one scene, a family member asks to sleep with a gun.

At last month’s commemoration of the 40th anniversary of Chin’s murder, “Bad Axe” was screened alongside “Who Killed Vincent Chin?” creating a throughline to the present-day AAPI experience. In the theater, Tajima-Peña praised “Bad Axe,” citing the casual racism depicted in a scene where a customer defies the restaurant’s mask policy.

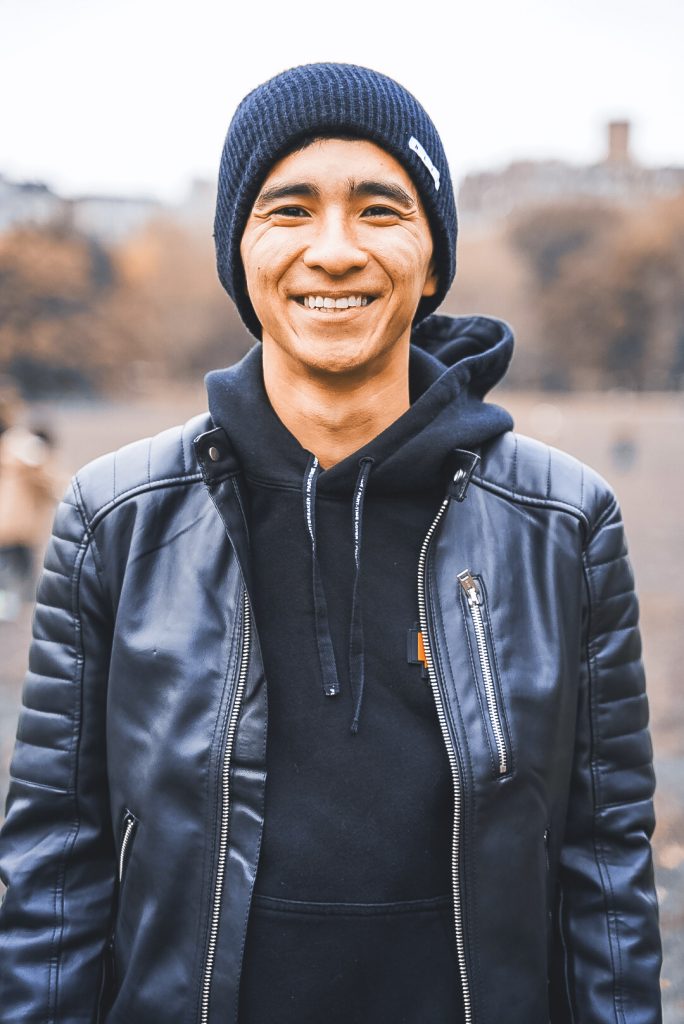

“People do want to listen to our stories because they’re important,” says “Bad Axe” director David Siev.

David Siev is a 29-year-old New York filmmaker who moved home to Bad Axe during the lockdown phase of the pandemic and turned the camera on his Cambodian Mexican American family to document mundane details and incidents of racial tension.

The film gives visual reference to data points — according to new research from the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism, anti-Asian hate crime increased nationally by 339 percent — similarly Tajima-Peña’s film introduced the world to Lily Chin, a mother whose raw grief and astute activism elevated her son’s name beyond a list of victims.

In one of the film’s most powerful scenes, Siev and his siblings attended a Black Lives Matter rally in Bad Axe after George Floyd’s murder and confronted armed counterprotestors later confirmed to be white supremacists.

What started out as a beautiful protest in a predominantly white city devolved for a few tense minutes into direct verbal confrontation, with Siev’s camera recording the adrenaline-pumping incident, including the anti-Asian slur hurled at Jaclyn Siev, the filmmaker’s older sister. This scene animates all the exploding line graphs and research — anti-Asian hate is real.

Siev released footage of the documentary, including the BLM scene as part of a crowd-funding campaign to finish the film. Hate mail and trolling comments on social media came in.

There is a saying that Chun Siev, the family’s patriarch, often says: “Teach your children well enough so they can eventually teach you.”

In one powerful Black Lives Matter scene, Jaclyn Siev confronts armed counterprotestors later confirmed to be white supremacists.

Chun Siev is a survivor of the Cambodian genocide who achieved the American dream by building a successful family business. The classic immigrant story rarely includes what it takes to hold on to the dream. Maybe that means fighting like hell against injustice.

“Standing up for other people shouldn’t be political,” said Jaclyn Siev in the film. “It’s just doing the right thing.”

Chin’s death marked the beginning of the Asian American movement, a time when the model minority myth was cast aside in favor of loud rallying cries for justice and representation. There was a time when AAPIs were invisible, said Zia, unprotected under civil rights laws until Chin’s case broke open the black-and-white binary. Forty years ago, the movement was the first step for the next generation of activists, writers and artists to tell their stories.

Our stories are what Dr. Michael Eric Dyson calls “the shape of our existence.” During the commemoration’s webinar, the Georgetown University sociology professor said our stories tell people, “In many ways you think I am the other, but I am really you.”

That’s why it’s important to continue to keep talking about Chin, said Siev. “And as the conversation continues to carry forward, I’m proud to carry that weight.”

Don’t Worry, Cuz

On a sunny June day in Detroit’s Forest Lawn Cemetery, the commemoration of Chin’s life was solemn and resolute. Guests were prompted to recite a call to action, “Let justice roll.”

In a time of rising hate, it’s hard to see what has changed since Chin’s death. History is always going to repeat itself, said Yoo, but so does hope, especially in the darkest hour.

“Hope also repeats itself.”

The mural of Chin currently stands in Detroit’s Old Chinatown on the corner of Peterboro Street and Cass Avenue — except for one weekend in June when its artist took it to Washington, D.C., to attend the Unity March, which brought together “the diverse Asian diaspora with multicultural partners across the LGBTQ+, Muslim, disability communities, Black, Indigenous and Pacific Islander, Latino and Arab American communities” to “advance socioeconomic and cultural equity, racial justice and solidarity.” Chin would have wanted to be there.

In his love letter, Lee wants to say, “Don’t worry about this. We got this. Don’t think that like this is the end of the story.”

He likes to think art is a sign of dignity, of not just surviving, but thriving. “Bad Axe” won the special jury award at March’s South by Southwest film festival in Austin, Texas, and will be released in theater and streaming platforms in the fall.

At Chin’s gravesite after the formal speeches concluded, the mood shifted from solemn to ebullient. Participants were given red flowers to lay at Chin’s grave. In the procession of people, laughter erupted.

A woman joked in Cantonese about all her hair turning white. These were all markers of resilience and joy.

Around Chin’s grave marker, the grass grows long and lush.

This is for our cousin Vincent.

Let justice roll.