‘Blossoms on a Poisoned Sea’ uses humanity, love story

to relay effects of the infamous environmental disaster.

By Gil Asakawa, P.C. Contributor

With modern awareness of environmental issues and concerns over climate and pollution of the Earth, it’s easy to think that the world is safe today from tragedies caused by man. But man-made industrial disasters still hit the headlines, from oil spills to the release of toxic chemical clouds and nuclear accidents.

One of the worst incidents of corporate malfeasance leading to a tragic environmental crisis was in the city of Minamata, Japan, on the island of Kyushu. Chisso Corp., a chemical manufacturer, dumped methylmercury into the bay where local fishermen depended not only for their living but for their daily sustenance. It turned out the population suffered from mercury poisoning for over a decade, starting in 1956, with effects lasting into the 1970s.

One of the worst incidents of corporate malfeasance leading to a tragic environmental crisis was in the city of Minamata, Japan, on the island of Kyushu. Chisso Corp., a chemical manufacturer, dumped methylmercury into the bay where local fishermen depended not only for their living but for their daily sustenance. It turned out the population suffered from mercury poisoning for over a decade, starting in 1956, with effects lasting into the 1970s.

Many readers of the old Life magazine may remember a powerful photo essay by renowned photographer W. Eugene Smith that was published in June 1972 that introduced the world to what was called Minamata Disease. Its victims suffered physical and neurological disabilities leading to death from the mercury, and whose children were born with deformities caused by the mercury poisoning. The essay helped bring world attention to the ongoing protests against Chisso Corp. by local citizens, and eventually forced the Japanese government to step in.

More recently, Johnny Depp played the role of Smith in a 2020 movie, “Minamata,” that focused on the photographer’s mission to tell the world about the disease.

Now, there’s a novel published earlier this year that tells the story of Minamata, not through news reports or the perspective of journalists, but through the experiences of two teenagers who fall in love as the city around them suffers from the ailment.

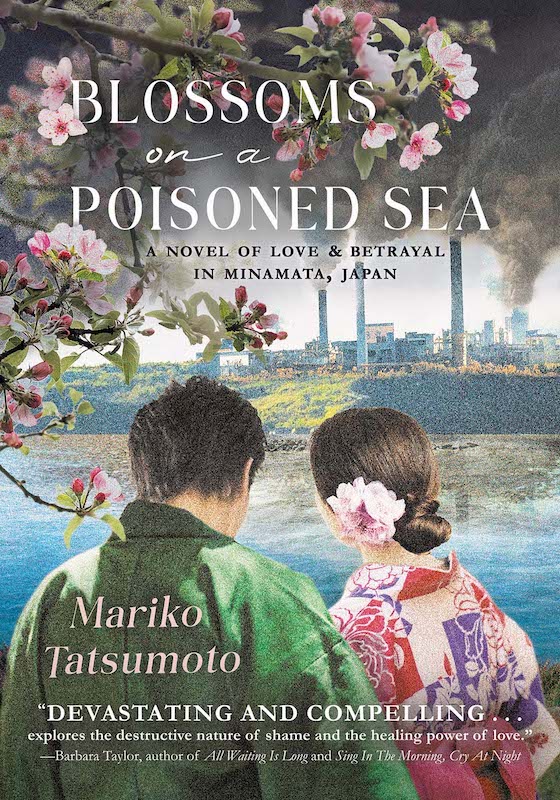

“Blossoms on a Poisoned Sea” by Mariko Tatsumoto is subtitled “A Novel of Love and Betrayal in Minamata, Japan,” and it captures the effects of the disaster. (Northampton House Press, 409 pages, paperback, ISBN: 978-1950668243, SRP $18.95)

The book’s protagonists, Kiyo Kuge and Yuki Akaji, see the devastation spreading through the city and learn its cause: the wastewater pouring from the factory into Minamata Bay.

The two meet by chance on their shared 14th birthday. Yuki is a talented artist who is the daughter of a fisher in a poor village on the outskirts of the city. Kiyo is the son of one of the officials who run the Chisso factory whose goal is to become a doctor, and lives a wealthy, privileged life.

Mariko Tatsumoto’s novel “Blossoms on a Poisoned Sea” dramatizes the infamous mercury poisoning of the denizens of the city of Minamata, Japan.

Tatsumoto unfolds the pair’s relationship like a beautiful origami sculpture, with layers of color and creases that fit together and move the narrative forward. Kiyo doesn’t buy into the class distinctions that his fashionable mother lives for, and aside from loving the bicycle he got as a birthday present (it helps him visit Yuki without taking a bus), he starts to buy food including fresh produce for her family with his allowance money. He also buys Yuki art supplies because he’s convinced she’ll be a famous artist someday.

To help Kiyo’s medical ambitions, Kiyo’s father gets him permission to shadow the plant’s doctor, Hajime Hosokawa, who begins to treat people including employees. Kiyo visits university researchers in nearby Kumamoto and helps to study “the Strange Disease.”

The mercury poisoning takes hold first in animals like cats, who suddenly act deranged and writhe uncontrollably as if they’re possessed to perform a demonic dance. But more and more people, especially the poor, who exclusively eat fish caught in the bay, begin to show signs including numbness in hands and feet, then lose the ability to walk and stand, and eventually to speak. They can only scream in agony as they die.

When Yuki’s uncle, who works for Chisso and lives with Yuki and her parents, gets the disease, their neighborhood shuns them. Tatsumoto reveals layers of prejudice in the city — between the wealthy and privileged (often connected to Chisso) and the poorer people, and then, as the disease progresses, between the healthy and the sick.

Tatsumoto, a retired attorney who lives in the mountains of southwest Colorado, vividly captures Japan of the 1950s and 1960s, down to details of daily life in a country that was obsessed with modernizing and recovering from the devastation of World War II.

She writes in part from lived experience. Tatsumoto was born in Japan to parents who were scientists and the family moved to the U.S. when she was 8 years old. Her father was a geochemist who was hired by the federal government and ended up determining the age of the moon.

She’s written a handful of young adult fiction titles, but “Blossoms on a Poisoned Sea” is her first adult novel. It started as a YA book, but Tatsumoto realized the “historical eco-fiction” theme, as well as the sexual undertones of the two protagonists’ blossoming love story should be aimed at a grownup readership.

Yuki sees the suffering from the villagers’ point of view, the people who had to keep eating the poisoned fish because unlike the wealthy folks, they couldn’t buy seafood from other cities. With that perspective, the book educates readers about the ecological disaster by showing its heartbreaking human perspective.

“I like to think of it that there are a lot of themes running through my book,” Tatsumoto said. “Of course, I tell it through the (love story of the) two protagonists. But I’m such a nerd, you know that I had to incorporate things like the corporate cover-up. I’m a real eco-tree-hugger kind of person. That was important to me to reveal, you know, what industrial pollution is all about.”

“Blossoms on a Poisoned Sea” reveals that tale in an artful, unforgettable narrative that speaks louder than history books or scientific texts, and serves as a warning to be watchful for future environmental tragedies.

This article was made possible by the Harry K. Honda Memorial Journalism Fund, which was established by JACL Redress Strategist Grant Ujifusa.