The Illinois senator’s ‘Every Day Is a Gift’ revisits the life of a soldier, senator and mother.

By George Toshio Johnston, P.C. Senior Editor, Digital and Social Media

Several years ago, in the mid-1980s, there was a 16-year-old in Honolulu working on the McKinley High School yearbook.

Although she loved the activity, her classmates and she were constantly exasperated by the seemingly absent-minded graphic arts teacher, who served as the yearbook adviser. Mr. Nakamura would regularly ask the girl and her friends to stay after school to fix something that he said he messed up on the yearbook’s layout.

Afterward, for making the students stay late, Mr. Nakamura would apologetically give them a few dollars and tell them to stop at the nearby Taco Bell, back when one could get two tacos for 99 cents. They happily and hungrily took advantage of their absent-minded teacher’s kindness, laughing at this bumbler behind his back.

Years later, when the teen had grown up, she realized all the kids that Mr. Nakamura asked to stay late were her fellow “food stamp” kids. She realized that the absent-mindedness was deliberate, his way of making sure they had enough to eat while sparing them of any possible feelings of shame for their circumstances.

It was those food stamps and other government programs that gave her impoverished family a helping hand, not to mention the kindness of people like her high school teacher, that compelled that girl who grew up to become a Democrat and, since 2017, the junior senator representing Illinois: Tammy Duckworth.

❖❖❖

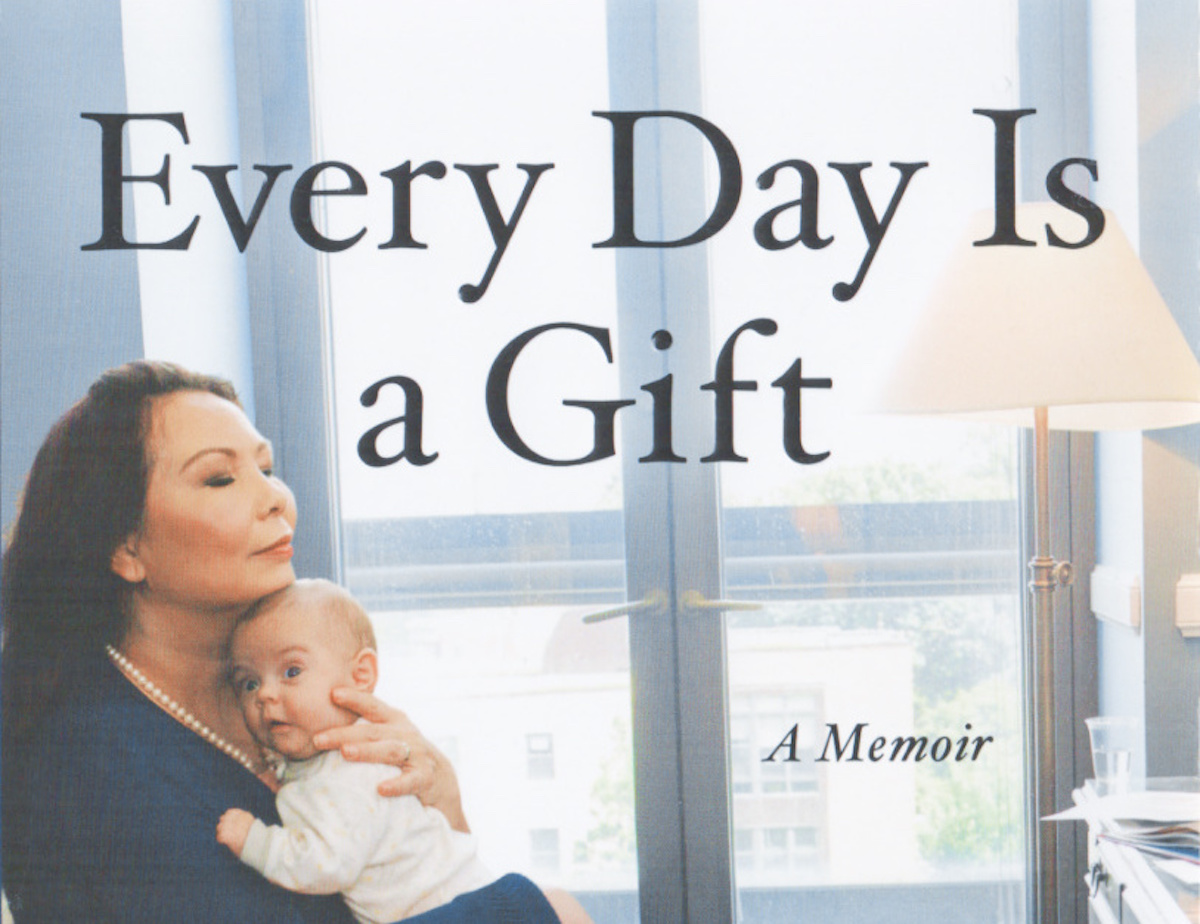

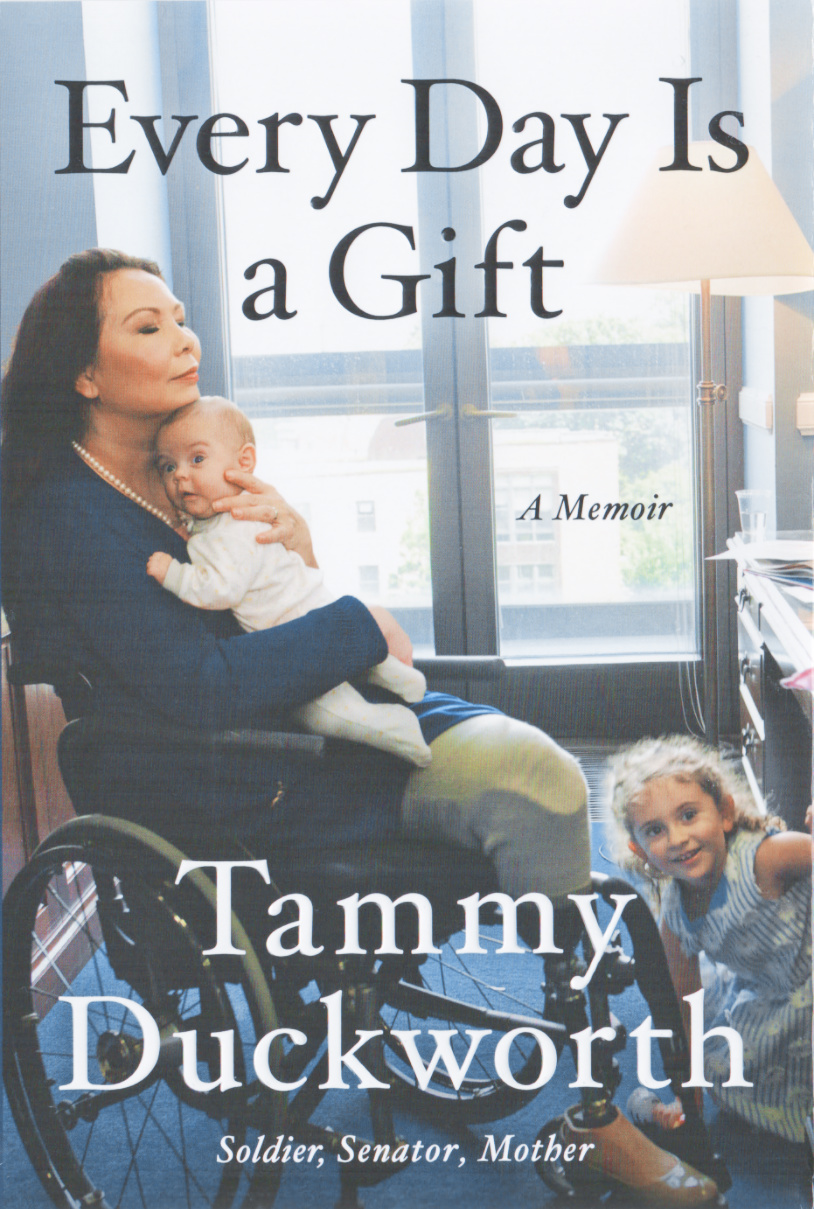

The preceding story is one of many contained in “Every Day Is a Gift” (ISBN-13: 978-1538718506), Ladda Tammy Duckworth’s 288-page memoir from Hachette Book Group, which was published on March 30.

The preceding story is one of many contained in “Every Day Is a Gift” (ISBN-13: 978-1538718506), Ladda Tammy Duckworth’s 288-page memoir from Hachette Book Group, which was published on March 30.

The book relates how the Bangkok, Thailand-born Duckworth and her family landed in Hawaii as a teen after growing up under relatively privileged circumstances in Thailand, Singapore and Indonesia.

But when, in 1982, Frank Duckworth lost his job managing a gated housing development in Indonesia for wealthy expatriate Americans and other Westerners, the family’s lifestyle began a serious turn for the worse. It was a downward slide that, once in the U.S., led them to scramble to earn every penny possible to stay afloat.

In “Every Day Is a Gift,” Duckworth also explains why she joined the Army and trained to become a helicopter pilot; where she met her future husband, Bryan Bowlsbey; and when her life was torn asunder after the chopper she was piloting in Iraq was downed by a rocket-propelled grenade, resulting in the loss of both her legs and a severe injury to an arm; and how she came back from that ordeal to become not just a United States representative and later, a senator, but also a mother late in life. All of those are among the many, many stories of adversity and triumph contained in the book.

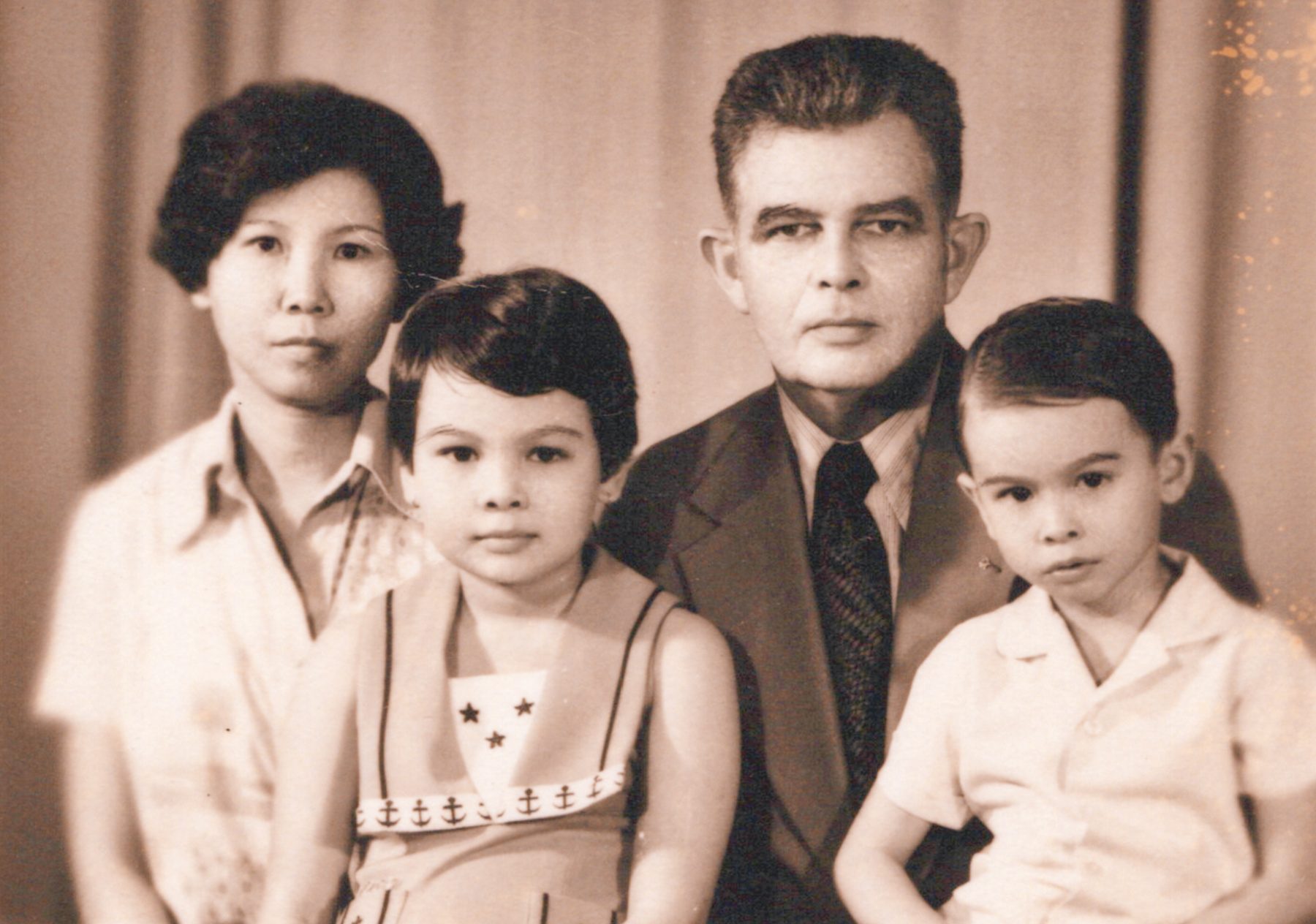

Duckworth’s improbable life story begins, of course, with her parents. Her Caucasian American father, Frank Duckworth, of Winchester, Va., fudged his papers to join the Marine Corps underage toward the end of WWII. (She believes he joined when he was 15.)

Years after transferring to the Army and earning his commission, he was sent to northern Thailand as a civilian employee of the Army (and a member of the Army Reserve) during the Vietnam War.

Tammy Duckworth’s mother, Lamai Sompornpairin, was an ethnic Chinese whose family fled China for Thailand to escape Communism and Mao Tse-tung. Frank and Lamai met while he was stationed in Thailand and she ran a shop with her brother. Frank fell for Lamai and pursued her, but Lamai, wary of the many examples of U.S. servicemen falling for and then abandoning Asian women (and their biracial-bicultural children), made him promise to take care of her and her family. He agreed.

They married — his second marriage, her first — and in due time, Tammy was born, followed by her brother, Tom.

❖❖❖

Duckworth told the Pacific Citizen that the impetus for the book began with a question asked a couple of years ago by her older daughter, Abigail O’kalani Duckworth Bowlsbey, who was born in 2014.

Sen. Duckworth

“Every night, I read a book with her, and then we have what we call ‘Mommy-Abigail’ time where we can ask each other anything, and we pinkie promise that we will never get mad at each other because of a question the other person asks,” Duckworth said. “One night, just about two years ago, she asked me, ‘Why did you go to war and you don’t have legs? It makes me mad because the other kids in my class have moms who have legs, and you can’t do a lot of the things that the other moms can do.’”

Duckworth said the question took her breath away. There was no simple answer to her child’s simple question. So, whenever she had a few minutes of downtime while, for instance, waiting to board an airplane, she began using the notes app on her smartphone to write notes for her daughter to explain what happened and why.

“I just started writing these little paragraphs to say, well, when Mommy was a teenager, I was really hungry because my daddy didn’t have a job, and we didn’t have enough food, but America gave me food stamps, and we were able to eat, so it was worth it for Mommy to serve in uniform,” Duckworth said.

“All these little stories that became the stories in the book were actually me trying to answer my daughter’s question of ‘Was it worth it for me to lose my legs for America?’ This book came as a result of that.”

Duckworth’s chief of staff, curious what her boss was doing on her phone, read the entries and concluded that there was enough material for a book proposal. As a result, the book came about very quickly, in nine or 10 months, with her collaborator taking that material and, as she put it, polishing it up.

❖❖❖

Asked whether the Thai people embrace Sen. Duckworth, she answered yes, saying, “I’m so proud of my Thai heritage. I’m proud to come from two different lands that value freedom. The word thai means ‘free,’ and Thailand literally means ‘land of the free,’ and now I’m a senator in another land of the free and home of the brave, the United States, so I’m proud of both, and I hope the Thai people are proud of me.”

Duckworth added, however, that she considers herself “100 percent American” because, as she noted in the book, she never felt like she fit in overseas. “I fit in best in the Midwest, and I’m a Midwesterner now,” Duckworth said.

As the book unfolds, Duckworth expresses a combination of respect and exasperation for her father, Frank Duckworth, who was parsimonious in his praise and encouragement for her, especially compared with her brother.

The Duckworth family, circa the early 1970s. Pictured (from left) are Lamai, Tammy, Frank and Tom Duckworth.

As she grew up, she also began to see through his all-knowing façade, writing, “It never occurred to me that he might not be right about everything; he would make a proclamation, and we all believed him. … My family would end up learning the hard way that Dad didn’t always know what he was talking about.”

She chalks it up to his generation. In the book, she relates how the closest he came to praising his daughter was, “Tammy’s not the smartest kid, but she works the hardest.”

Duckworth also said that initially she didn’t intend to include much about him.

“It’s funny. The stories about my father sort of emerged as I wrote the book. I never meant to have my dad in there, if there is any kind of a theme, but it became a theme in the book, and I think most people reading it, especially daughters of fathers, might see parallels in the complicated relationships between dads and daughters, especially eldest daughters who are trying to get their approval and can’t quite ever get it. That’s just the way it is.”

(As for whether Duckworth ever heard her father praise her before his death in 2005, you’ll have to read the book to find out.)

❖❖❖

For Duckworth, the trajectory of her life is inseparably intertwined with the years she spent in the Army.

“It’s a pure meritocracy. It didn’t matter when I showed up at basic training that I was a little mixed-race half-Asian girl in my platoon,” Duckworth said. “It didn’t matter who I was. It just mattered whether I could shoot straight. … That pure meritocracy is what I fell in love with. I ended up becoming a lifer and did 23 years.”

Duckworth at flight school, where she fell in love with flying and learned to become a helicopter pilot. (Photo: Duckworth family)

Part of that saga, of course, includes the day in November 2004 when the Black Hawk helicopter Duckworth was piloting was shot down by an RPG (rocket-propelled grenade), which resulted in the loss of both of her legs and a shattered right arm, a story that is retold excruciatingly in her book.

Because she was rendered unconscious shortly after the chopper crashed, Duckworth had to piece the story together of the aftermath from the accounts of others who either survived the attack or helped in her rescue.

Like many thousands of wounded soldiers before her, Duckworth would, after a stop in Germany, be sent to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md., where she was kept under sedation for days. While she has no memories of that period, for her husband, Bryan Bowlsbey, and parents, who flew in from Hawaii, it was a time of emotional and psychological torment. In all, Duckworth spent 13 months at Walter Reed.

Her recovery and eventual successful foray into politics would put her into a very exclusive club of former military personnel who became U.S. representatives and senators and an even smaller club within that one: disabled military who became senators, with Bob Dole of Kansas and Daniel Inouye of Hawaii preceding her.

Duckworth is also in a club that Dole and Inouye could never join, as she is the first senator to give birth while in office, with the arrival of her second child, Maile Pearl Duckworth Bowlsbey.

❖❖❖

When Duckworth was writing her book, there was a different occupant in the Oval Office who was known for giving others derisive nicknames, a fortunate son who attended military school but avoided serving in Vietnam thanks to a doctor who diagnosed him with bone spurs in his feet. “Candidate Bone Spurs,” as Duckworth infamously called the one-term president, would lose in November 2020.

In the runup to the election, his eventual successor was vetting potential running mates. Duckworth was said to be among that group, and while ultimately she wasn’t chosen, her profile nevertheless rose.

And that new president, Joe Biden, once served a former president whose life and career has parallels to Duckworth’s: being biracial, growing up in Asia and Hawaii, making Illinois an adopted home, becoming a senator, writing an inspirational book and becoming president. Is the path walked by Barack Obama one that might be taken by Tammy Duckworth?

Asked if that might be the case, Duckworth’s answer was preceded with a hearty laugh.

President-Elect Barack Obama (L) embraces Iraqi war veteran and Illinois State Director of Veterans Affairs, Tammy Duckworth (R), after the two placed a wreath at the Bronze Soldiers Memorial in honor of Veteran’s Day Nov. 11, 2008 on the Lakefront in Chicago, Ill. (Photo: Stan Honda/AFP via via Getty Images)

“Oh, no! I love being in the Senate. Are you kidding me? I can’t believe I’m a U.S. senator. I love my job. My heroes are the Daniel Inouyes and the John McCains and the Bob Doles, the people who served in the military and then came back and built a body of work in the Senate that really made American lives better and found a different way to serve than in uniform. That’s what I want to do. It’s very flattering to be compared to Barack Obama, but I’m no Barack Obama, and frankly, I don’t want to be. I love where I am.”

Duckworth at Walter Reed receiving guests Rob Schneider (second from left) and Adam Sandler (fifth from left) and others who visited to offer encouragement to the wounded. (Photo: Duckworth family)

But, asked if she could become the president, even though she was born in Thailand, she was quick to note that the law is on her side, since “natural-born citizen” does apply to her through her father, a U.S. citizen, just as it did to Sen. John McCain, who was born in Panama, when he ran for president.

“The book really was me trying to do something for my daughters and friends noticing that this would be a really good book,” said Duckworth. “I never really intended to write a book for anybody, other than my girls.

“It’s really a love letter to my country,” she continued, “answering my question for my daughter, ‘Is America worth it?’ And my answer is, ‘Yes.’ That’s why it’s called ‘Every Day Is a Gift,’” Duckworth said. “And I end the book with the letter that I wanted to write to my girls about why America is worth it. And, I hope someday they find their way to serve this country, too, maybe not in uniform. but that they give something back someday.”

The Pacific Citizen will have a drawing to give away one copy of “Every Day Is a Gift” to a P.C. reader. Mail an envelope to: Pacific Citizen, ATTN: Every Day Is a Gift Book Drawing, 123 Astronaut Ellison S. Onizuka St., Suite 313, Los Angeles, CA 90012. Letters must be postmarked by June 18. The winner of the drawing is asked to promise to write a Letter to the Editor giving his/her thoughts on the book.

EXCERPT

‘Every Day Is a Gift’

By Sen. Tammy Duckworth

(Following is an except that has been reprinted with permission from its publisher, Twelve/Hachette Book Group. All Rights Reserved.)

Chapter 2

In 1974, my dad took a job stringing telephone wires for a United Nations Development Programme project in Phnom Penh. At the time, Cambodia was embroiled in a violent civil war, with communist Khmer Rouge insurgents seizing territory controlled by the U.S.-backed Khmer Republic, mile by bloody mile. The fighting had been raging for nearly five years, a savage echo of the war going on just across the border in Vietnam.

The situation in Cambodia was dangerously unstable, but at age six, I had no idea about any of that. I loved living in Phnom Penh. In Bangkok, we’d had a small apartment, but here we had a multistory house with a garden. Because we were a UN family, we had security—a gate surrounding the house, with an armed soldier posted out front. I didn’t understand that the guards’ fully loaded rifles were more than just decoration, or that the threat of violence in the capital was real and ever present. I just liked playing with the soldiers and trying to learn enough words in the Khmer language to talk to them.

When I think back on our time in Cambodia, I think of drives down wide boulevards lined with mango trees and bougainvillea flowers. I remember the smell of French boules, crusty and golden, their interiors fragrant with warm, yeasty, deliciously doughy bread. Whenever Mom would take Tom and me to the market, she had to buy two or three at a time, because we would tear into them as soon as we got to the car, devouring an entire boule before the driver got us home. Phnom Penh was colorful and fun, and the people at the market always seemed so friendly.

But then, I remember another scene. My mom and I were in the car, heading to market, and suddenly she grabbed me and shoved me headfirst down to the floorboard. She yelled at the driver to turn around, and I lay there confused, my face flat against the mat and Mom’s hand pressed to the back of my head to keep me from looking up. A bomb had exploded in the market just minutes earlier, and she was desperately trying to protect me from seeing the blood and body parts scattered among the stalls. The driver floored it, and we raced straight back to the house.

But then, I remember another scene. My mom and I were in the car, heading to market, and suddenly she grabbed me and shoved me headfirst down to the floorboard. She yelled at the driver to turn around, and I lay there confused, my face flat against the mat and Mom’s hand pressed to the back of my head to keep me from looking up. A bomb had exploded in the market just minutes earlier, and she was desperately trying to protect me from seeing the blood and body parts scattered among the stalls. The driver floored it, and we raced straight back to the house.

Somehow, I still wasn’t scared, even as the bombings inched closer and closer to our home. My parents used to take Tom and me to the roof so we could see the bombs drop over the river and the flares soaring into the sky. “Look, Tammy,” my dad would say. “Look at the pretty fireworks.” I believed they were fireworks, so when I’d hear the sounds of explosions and see the rockets lighting up the sky, I never felt scared.

Dad also brought us to the airfield to see the C-130 planes that sometimes ferried him to Laos and Thailand for work. A couple of times, he brought us along for rides to Bangkok, to see our relatives. My mom wasn’t keen on this, but to me, there was nothing cooler than sitting in the back of one of these big planes, looking out of the lowered tailgate, and seeing jungles, rivers, and villages whiz by below. I couldn’t have imagined then that one day, thirty years later, I’d be piloting my own aircraft over palm groves and villages not so different from these.

In later years, when I asked my mom about our family’s experiences in Cambodia, she would describe this time as a difficult one. While my memories are of colorful street scenes and fresh bread, hers are of being mostly confined to our gated home as the fighting closed in on the capital. It must have been incredibly stressful for her, worrying about the safety of her young children in a war zone that was only growing hotter. She also never knew if my dad would return home safely each night from his job sites across the city. Yet when most Americans started flooding out of Phnom Penh in early 1975, my dad insisted that we stay. He believed that there was no way the United States would allow Cambodia to fall to the Communists, and that any day, American troops would arrive to fight the Khmer Rouge.

“They’re coming,” he’d say. “You’ll see.” He was a firm believer in the domino theory, that if one country fell to communism, others would soon follow suit. The war in Vietnam had ground to a bloody stalemate, and if we couldn’t defeat the Communists there, then surely we could— we had to!— erect a firewall in Cambodia. My dad trusted that the Americans would do everything they needed to do to hold the line in Southeast Asia. He refused to believe that our government would do anything less.

But as the fighting drew ever closer to our home, my dad finally realized that he couldn’t keep us there anymore. So in early April of 1975, he got Mom, Tom, and me on the last commercial flight heading out of Phnom Penh. In my recollection, we just went to the airport and got on the plane. Years later, though, my mom told me that in the airport, we had to sit on the floor, our backs pressed to a wall, crouching below window height to avoid bullets that were flying overhead.

We made it safely to Bangkok, and shortly after that, my dad told my mom in a phone call that a bomb had blown up right outside our house. The explosion had sent shrapnel flying through a window and over the bed where he was sleeping, peppering the wall across the room. That same week, he was up a telephone pole, stringing wires with a Cambodian worker, and a rocket landed at the bottom of the pole. It didn’t explode, thank God. But my dad realized that he too had to leave, or risk losing his life there.

Dad was evacuated in Operation Eagle Pull—he final wave of U.S. military transport planes to leave Phnom Penh, on April 12. By that date, the capital was surrounded by the Khmer Rouge, completely cut off from supplies and bombarded by endless waves of artillery fire. Five days later, on April 17, 1975, the Khmer Rouge stormed in, and Phnom Penh fell. We had made it out just in time.

From my family’s safe haven in Bangkok, we watched TV news coverage of the chaos erupting across Indochina. Two weeks after Phnom Penh fell, Saigon did too, as North Vietnamese and Vietcong troops surged into the capital. And many of the Americans in Saigon did exactly what my dad had done, waiting until the last possible moment to get out.

At first, they evacuated in airplanes. But after the North Vietnamese Army launched bombing attacks on Tan Son Nhat Airport, the United States initiated the largest helicopter airlift in history, Operation Frequent Wind. In less than twenty- four hours, our helicopters evacuated more than 1,000 Americans and 5,000 Vietnamese from Saigon to U.S. aircraft carriers in the South China Sea.

Tammy Duckworth at 16, taken at Camp Castaway, off the coast of Malaysia. (Photo: Duckworth family)

On TV, I saw the famous image of people pushing their way up a ladder, trying to board a Huey perched on the roof of a Saigon building. Decades later, I would begin my own military service by learning to fly those same Huey helicopters, and much of my training—and the training of other pilots I’d fly with—would come from Vietnam War Veterans. Little did I know it then, but the tactical flying skills these helicopter pilots had learned in Vietnam would one day save my own life.

I also saw much more disturbing images, of rickety boats crammed with frightened people and their crying children. In the spring of 1975, tens of thousands of Vietnamese, some with nothing more than the clothes on their backs, clambered into fishing boats, trawlers, and sampans in hopes of making it to one of the many U.S. warships anchored off the coast. This was the first wave in what would become a nearly two-decade exodus of hundreds of thousands of “boat people” from Southeast Asia.

Watching these scenes as a seven-year-old child affected me, even though I was too young to fully take in what I was seeing. I understood that the United States was rescuing people with helicopters, and that the people who crowded onto those boats were looking to us for protection. I wasn’t sure exactly what Communists were and why they wanted to do such terrible things, or even what those terrible things were. I just knew that we had been at war with them, and now they were winning and the Americans were leaving. The local people were desperate to go with the Americans, because they needed our help. This felt personal for me, because I was American and so was my dad. I was proud that we were the good guys, but also confused about why Americans couldn’t save all those people.

Seeing those TV images of people crammed into boats in 1975 made a strong impression on me. But I also saw the plight of refugees in person. My dad got a job working with UN refugee programs, delivering aid to camps filled with Cambodian and Vietnamese people who’d managed to escape to Thailand. A couple of times he brought me along, so I could watch him deliver big bags of rice and boxes of medical supplies stamped with the American flag and see how people’s faces lit up. Those moments intensified the pride I felt. From a child’s perspective, this all seemed very simple: Americans were the ones who helped people in need, who opened their doors and took in refugees, who cared.

I had the same feeling when my dad took us to see the U.S. diplomats cutting ribbons to open new hospitals and schools in Bangkok. I would eagerly tell other people in the crowd that my dad was American, and because of that, I was American. I still had never been to the United States, and wouldn’t get there for five more years. But these experiences marked the beginning of my deep feeling of patriotism for this country.

From the book “Every Day Is a Gift,” (Copyright © 2021 by Tammy Duckworth) Reprinted by permission of Twelve / Hachette Book Group, New York, NY. All Rights Reserved.