Kazuo Komoto greets First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt while convalescing at a hospital in Fiji in August 1943. He was shot in the leg while stationed in New Georgia, Solomon Islands. He was the first Nisei in WWII to receive the Purple Heart. His story is among several Nisei who served in the Army‘s Military Intelligence Service during WWII as relayed in the new book “Bridge to the Sun.”

Bruce Henderson’s book shines a light on the saga through the eyes of six Nisei linguists.

By George Toshio Johnston, Senior Editor

If you as a Pacific Citizen reader happened to catch an episode of CBS’ “60 Minutes” from a few months ago and thought one of the stories sounded familiar — about individuals from an ethnic group of Americans who were fluent in the language and culture of one of the Axis powers during World War II who were then tapped by the Army to enhance and sharpen their skills via an intensive training program so they could be utilized as translators, interpreters and interrogators — you weren’t alone.

But it wasn’t the story of Japanese Americans who served in the Military Intelligence Service in the Pacific Theater — it was the story of the so-called Ritchie Boys, most of whom were German-born Jews, who served in the European Theater.

“Bridge to the Sun” author Bruce Henderson.

It was a story familiar to Bruce Henderson.

As a Vietnam War veteran (Navy) turned journalist, teacher (University of Southern California and Stanford) and author of more than a dozen nonfiction books, including several about WWII, Henderson wrote 2018’s “Sons and Soldiers: The Untold Story of the Jews Who Escaped the Nazis and Returned with the U.S. Army to Fight Hitler.” It was about the Ritchie Boys, and the book was among the resources “60 Minutes” used to research its segment about them.

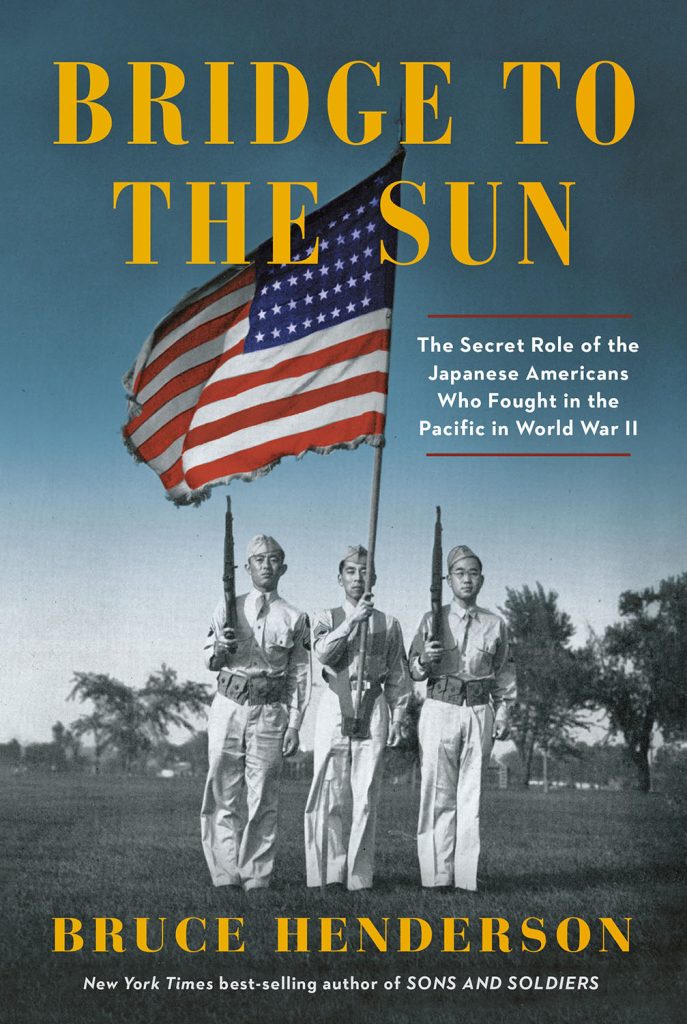

It’s fitting that his follow-up book is about the Nisei who served in a similar capacity to that of the Ritchie Boys, but in the Pacific Theater. Published on Sept. 27, that book, more than four years in the making, is titled “Bridge to the Sun: The Secret Role of the Japanese Americans Who Fought in the Pacific in World War II” (Knopf, 480 pages, ISBN 9780525655817, SRP $35).

It also contains an afterward written by Gerald Yamada, president and past general counsel of the Japanese American Veterans Assn. and a past president of the JACL’s Washington, D.C., chapter.

Thus, “Bridge to the Sun” might be considered the cousin to 2021’s “Facing the Mountain: A True Story of Japanese American Heroes in World War II,” written by Daniel James Brown, the focus of which was on members of the 100th Battalion/442nd Regimental Combat Team, also comprised mostly of Nisei who also served the Army but in the European Theater (see May 7, 2021, Pacific Citizen tinyurl.com/398wb235).

In “Bridge to the Sun,” Henderson chose six veterans — his “cast,” as he called them — to focus on in order to convey the overarching story of the MIS, an approach similar to that used in “Sons and Soldiers.” Those men were Nobuo Furuiye, Takejiro Higa, Grant Hirabayashi, Kazuo Komoto, Hiroshi “Roy” Matsumoto and Tom Sakamoto.

“Bridge to the Sun” focuses on six veterans to convey the MIS story.

The following is an edited Q & A between Henderson and the Pacific Citizen about his book, “Bridge to the Sun.”

Pacific Citizen: How did you become aware of the MIS saga? What drew you to this particular story?

Bruce Henderson: It was strictly a serendipity kind of thing. I was at the archives, researching “Sons and Soldiers,” which was the Ritchie Boys. I’ve certainly seen movies and read books about the 442nd, but I had no idea that any Nisei were sent to the Pacific — and here I had already written several WWII books, including two of them that were sitting in the Pacific Theater.

So, I didn’t know [about the MIS], and I knew if I didn’t know, probably a lot of other people didn’t know their story. So, I made a note to myself, “You know, when I finish this book on the Ritchie Boys, I’m going to come back to this” — and I did.

P.C.: Do you see parallels between the Nisei MIS story and the Ritchie Boys story that you worked on?

Henderson: Absolutely there are parallels between the two stories. Not only were they trained largely in secret during the war by the Military Intelligence Service, but they also trained really for the same mission, only in different theaters.

Also, each had to overcome their own brand of prejudice, if you will. For the Ritchie Boys, their motivation was very strong in terms of defeating the Nazis and (Adolf) Hitler — and many still had their families over there. They spoke German, and they often had really thick German accents. So, there was a period of time when people wondered if they could be trusted.

Brothers Warren and Takejiro Higa, both of whom served in the Army’s Military Intelligence Service. Warren Higa had been training with the 442nd RCT at Camp Shelby, Miss., before transferring to Camp Savage, Minn., to serve in the MIS and join his younger brother.

And then you’ve got the Japanese Americans, the whole story there, not only after Pearl Harbor, but also before Pearl Harbor, when there was all of this anti-Asian immigrant stuff going on. In most cases, they could not even own the land that they farmed. The [Issei] parents, even if they wanted to, couldn’t become naturalized American citizens.

Now, here come their offspring, the Nisei, and war breaks out and they’ve got the face of the enemy. They (Issei and Nisei) get rounded up and put into camps and about 60 percent of the 120,000 that get put into camps were American citizens. They’re there because they are not considered trustworthy. So anyway, within a few months, here come the Army recruiters into camp. “We put you here — but Uncle Sam needs you.” They needed them because of the language skills that they had to go into the Pacific.

And the Kibei — initially the U.S. government was saying, “Anybody who has spent any time in Japan, they’re highly suspect. They could be emperor worshippers, and we can’t trust them if they’ve gone to school in Japan.” Well, guess what? Those were the most valuable to the MIS because they were fluent in reading and writing and had been educated in Japan. So, yeah, there were a lot of parallels on these two books.

P.C.: At this point, most of those who served are deceased, and those still living may be incapacitated physically or mentally. If you didn’t do in-person interviews, what was your methodology in researching the MIS story?

Henderson: First and foremost, I needed veterans to follow in the book. There was only one of the six still alive when I started the research, and he was already going on 100. Shortly after I spent a couple hours with him, he died. And if I hadn’t had other material on him, I wouldn’t have been able to include him.

The oral histories are sort of the backbone. If you go to my sources in the back of the book, they’re listed by chapter, and you will see repeatedly the oral histories. There are different groups that over the years have brought these veterans in — Go For Broke is certainly one. Denshō is another. To get other materials, I reached out to families. What did they leave behind? In some cases, there were memoirs that they had written, either privately published or unpublished. I got letters when I could get them.

My book is narrative nonfiction, which means that it should read like a novel and not a work of dry history. But nothing is made up. Not any dialogue, I don’t put thoughts into people’s minds — it’s got to come from somewhere. About two years alone was the research before I even wrote the first chapter. I always want to get about 90-95 percent of the research done before I start writing. There’s always stuff that comes up when I’m writing, like a question or two, but generally, I want the bulk of the research done before I start writing.

P.C.: Has there been any interest to have it translated into the Japanese language for the Japan market?

Henderson: Interestingly, the first translation rights that we sold were to China. And there are actually some discussions going on now in Japan about a translation. But nothing has been finalized as yet. There’s also some talk in Hollywood with some people who are interested in adapting “Bridge to the Sun” as a limited series. We’re really pushing to get AJA producers and directors involved.

I think timing-wise, it seems like there’s never been a better time than right now in this country to have stories like this come out. Sadly, these anti-immigration sentiments are still way too prevalent in this country. We’re in an America today that too often prejudges people based on race, ethnicity, countries of origin — and a message like this, this timeless message of service, of courage, of a really true patriotism — I think it should never be forgotten.

On leave to visit to see family incarcerated at the Gila River War Relocation Authority Center in Arizona, Kazuo Komoto shows his younger brother, Susumu, the Purple Heart he received after surviving a bullet wound to his right leg.