Gil Asakawa

Let me say right upfront: I don’t like “Miss Saigon.”

The musical has been a megahit staple of the stage since it made its debut in London in 1989 and then Broadway in 1991. It ran for a decade in New York and was revived in 2017. Touring versions have crisscrossed the U.S., including a stop in Denver in September.

“Miss Saigon” makes lots of money for its producers and the theaters that can accommodate its huge and complex stage sets and large number of cast members. It’s a popular musical with popular, instantly recognizable songs.

But, I don’t like “Miss Saigon.”

If you don’t know the show’s plot, it’s about a Vietnamese woman and a white American GI who fall in love during the last days of the Vietnam War. They’re married, and though he plans to take her back to the U.S., they get separated during the fall of Saigon. Chris, the soldier, doesn’t find out until three years later that Kim, his wife, had a son, Tam. By then, he’s remarried to a white woman in Atlanta, and together they travel to Vietnam to try and establish a relationship with Kim and Tam.

Kim is devastated when she learns that Chris has remarried, and in the end (spoiler alert), she kills herself so that Chris and his wife, Ellen, would be forced to take Tam back with them and raise him in America, which had been her dream since the end of the war.

It’s a pretty conventional love story, and if the specifics of the plot seem familiar, it’s because it’s a modernized version of Giacomo Puccini’s “Madama Butterfly,” the 1904 opera about a white American naval officer who marries a Japanese woman, leaves her and returns to Japan with his “real” wife, who is white. The Japanese woman, Cio Cio (cho-cho in Japanese means “butterfly”), kills herself at the end of the opera.

I don’t like “Madama Butterfly,” either.

“Miss Saigon” DCPA posters (Photo: Gil Asakawa)

“Miss Saigon” hypnotizes its audiences with its production pomp and dramatic musical thrills, but the story is the same as a century ago, and it seems even more outrageously anachronistic and out-of-step today, in the #MeToo era, and with our heightened awareness of racial stereotypes, especially of Asians.

The musical is about cultural and physical imperialism, white privilege and savior complex, as well as unabashed misogyny and sexism, written with a condescending attitude by white people looking back at a terrible and tragic time in the history of Vietnam.

It’s not all awful and negative. The second act opens with “Bui Doi,” a touching number about veterans and their responsibility for leaving behind the bui doi, or “dust of life,” the Amerasian children left behind by departing GIs. The song is the moral center of the production.

There have been protests at many productions of “Miss Saigon” to decry its racial and sexual stereotypes — available, weak and submissive Asian women and ineffectual, impotent Asian men. In one much-publicized fiasco during a Madison, Wis., stop of this current tour, the theater agreed to schedule a community panel discussion about the stereotype, then canceled it at the last minute, pouring fuel on the fire of protest. (It should be noted that the New York producers of the tour were all for the community panel discussion, but the theater canceled it.)

So, when the Denver Center for the Performing Arts announced it was bringing “Miss Saigon” for a two-week run, a group of Asian American Pacific Islander community members met with DCPA management to share our concerns. To our surprise, they were open to our comments and willing to work with the community to find ways to make “Miss Saigon” a learning experience for audience members.

For starters, they published accurate portrayals of Vietnamese refugees from our community in interview articles on its website and program book, telling their stories.

We suggested a talk-back panel discussion with local Vietnamese community members, and the DCPA countered that they could schedule an unprecedented series of talk-backs during the production and include members of the cast and crew in addition to community members.

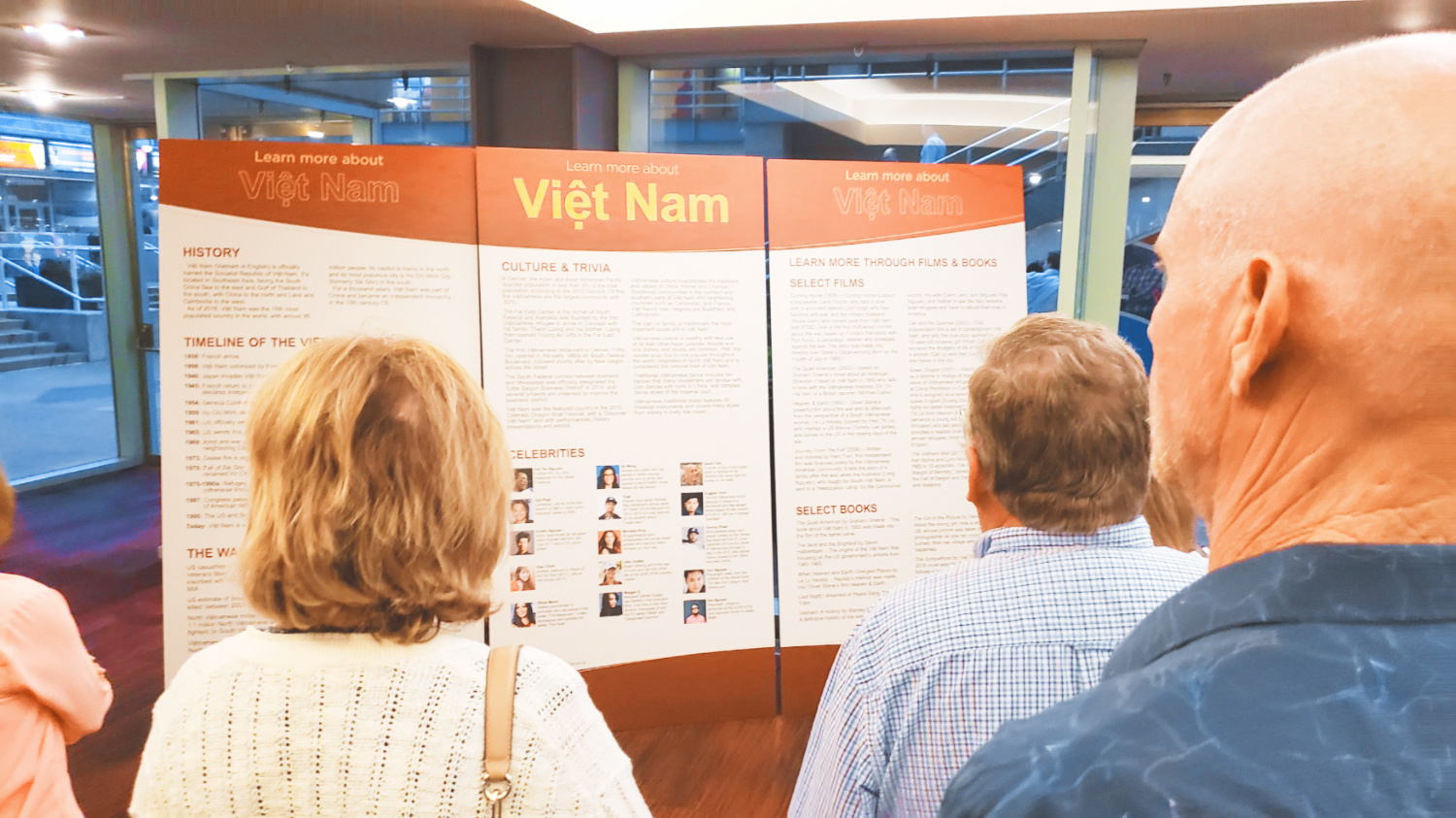

I also helped research facts about Vietnam, the war, its aftermath, pop culture trivia and movies and books for more information, which the DCPA printed on a triptych of huge poster boards that audience members clustered around and read before the curtain calls.

I don’t like “Miss Saigon.” But it’s unrealistic to think that we can make the musical go away and be put on a shelf to turn to dust. All of the DCPA’s efforts allowed room for dialogue around the troubling issues that still pervade the production. And that, to me, is a big win — just to be able to have the conversation.

So, can we talk?

Gil Asakawa is former chair of the Pacific Citizen Editorial Board and author of “Being Japanese American” (Second Edition, Stone Bridge Press, 2015). He blogs at www.nikkeiview.com.