Norman Mineta is the subject of a documentary that chronicles his remarkable life and achievements. (Photo: Jackie Lovato)

The documentary recounts the service and achievements of a true American statesman.

By P.C. Staff

In the new documentary “An American Story: Norman Mineta and His Legacy,” there is a scene in which the subject — a Korean War veteran, a former U.S. representative for California, a Cabinet member under presidents both Democrat and Republican and a man who has an international airport named for him — responds to a question about why he always wears an American flag lapel pin in public.

“I still get treated like a foreigner and feel that. So, I always wear the flag,” Norman Yoshio Mineta said, quietly and matter-of-factly. A holdover from having been incarcerated as a boy with his family at the Heart Mountain WRA Center in Wyoming, mayhap?

“Am I really being accepted as an American citizen?” he asked. Then, with a bit of a smile, he added: “I want to make sure everyone knows I am.”

Mineta’s answer stunned the film’s co-producer and director, Dianne Fukami.

“Here’s a guy who has had a lifetime of public service, right, and he still feels like a foreigner in his own country?” asked Fukami after hearing Mineta’s answer to her off-screen question. “What you can’t see are the tears running down my face because I felt so sad and moved by what he’s saying.”

Fukami said Mineta’s answer was “sort of an epiphany” for her.

“There are so many people, unfortunately right now, in this country, who understand exactly the way he feels, whether you’re Asian American, whether you’re African-American, whether you’re Latino or any other,” she said.

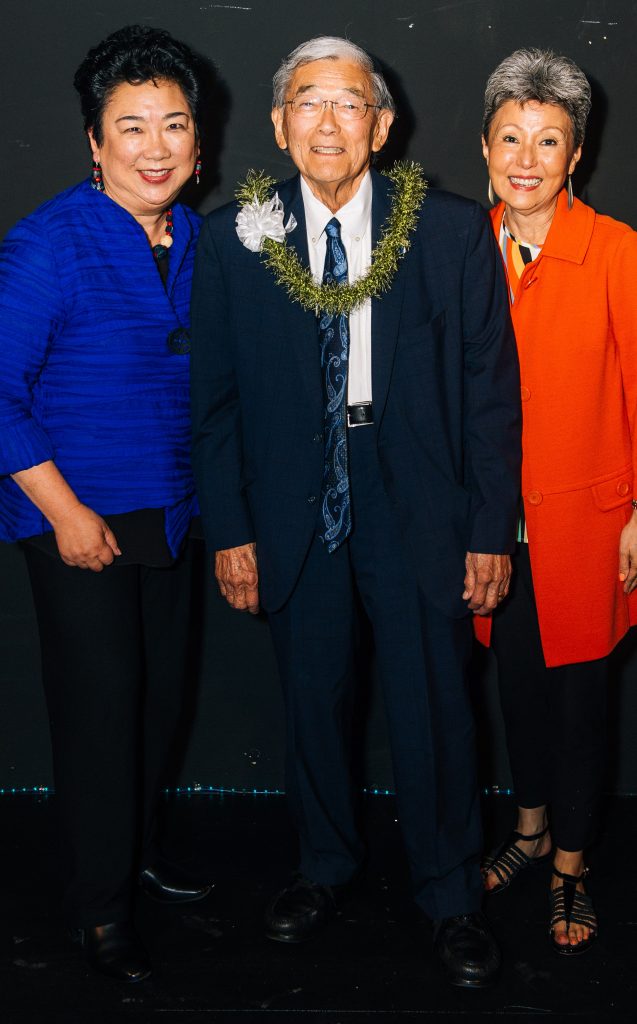

Norman Mineta is flanked by the documentary’s principals, Dianne Fukami, director and co-producer (left), and Debra Nakatomi, co-producer. (Photo: Mineta Legacy Project)

“In the film when he references that, he talks about being in close quarters, like in an elevator,” added co-producer Debra Nakatomi. “He just wants people to be sure that people know that he’s American.”

Now in his late 80s, the time seems right for the San Jose, Calif., native son to pause, assess and reflect on his life’s achievements and the political battles fought. Fortunately, the wins appear to outnumber the losses.

“For an 87-year-older, I think I’m fine,” he told the Pacific Citizen.

The tasks and obstacles that needed to be overcome in telling Mineta’s inspiring story to pass it on to younger and future generations — and getting his cooperation — is almost worthy of a documentary unto itself.

Fortunately, there were a couple of dogged filmmakers up to the task, in San Francisco-based Fukami and Los Angeles-based Nakatomi.

The pair met in 2009 when both were delegates in the Japanese American Leadership Delegation, sponsored by the U.S.-Japan Council and Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

“I think, speaking for myself, we always knew we wanted to stay connected at some level,” Nakatomi said.

The disastrous 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan would lead to their first professional pairing, culminating with the 2013 documentary “Stories From Tohoku,” with both co-producing and Fukami directing.

But prior to that documentary, Fukami had made several attempts to get Mineta’s cooperation to produce a documentary about him. As a Bay Area resident, she and her family knew of his reputation and achievements.

“He was sort of a hero to us,” Fukami said. “I had always had the idea of doing something on him, but when I tried to talk to him about it, oh, 17 years ago, he would demure. He was very busy at the time with his career.”

Fukami added that Mineta was very soft-spoken and modest.

“He would say to me, ‘Oh, nobody cares about me. I’m just an average Joe,’” she said.

While neither Fukami nor Nakatomi believed that for a second, the irony was that when they applied for a grant from a large, well-known funding entity, that was sort of the answer they got when their proposal was rejected.

As luck would have it, in 2012, at a U.S.-Japan Council conference in Seattle, when Fukami saw Mineta and asked him the obligatory, “How about that documentary?” question, he surprised the pair with a “Let’s talk” response.

Subsequently, a long lunch meeting took place in San Jose, with the involvement of Mineta’s wife, Deni. Fukami and Nakatomi told him their goal was to air the completed project on PBS — but that Mineta would have no editorial control on the subject matter, and they would need access to family photos and home movies, plus they would need to interview him, his family members, as well as former political allies and adversaries alike.

“After hearing all that, Norm said, ‘OK, I understand,’” said Fukami. “And then we said to him, ‘Now that you’ve finally said yes, there are other filmmakers who may be interested in your story. Some of them will have more experience and more talent. Do you want to postpone making your decision and consider all your options?’”

Fukami said she didn’t want him to feel that he was forced into a decision or obligated to them.

“I wanted him to know that once he had made that decision, he was free to explore that a little more,” she said.

Fukami said Mineta paused for a second and answered, “No. I’ve got my team right here.”

As for what they thought finally prompted Mineta to give them the greenlight, Nakatomi said, “I think he thought it was time. Of course, we like to think that he was comfortable with us.”

Getting Mineta’s cooperation was vital — but so, too, was getting the necessary funding. The producing duo had their eyes set on a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

“We started doing a lot of grant applications initially, and one of our biggest goals was getting an NEH grant,” Fukami said. “We came very close to getting a nice sum of money from the NEH. However, we didn’t make it.

“They read you some of the comments when you ask for feedback,” Fukami continued, “and we were told [that] although the panel who judged our submission was very interested in the project, they felt that Norm wasn’t a household name — and, bear in mind, this is 2014, 2015 — and that he was not ‘sexy’ enough to generate a lot of interest and so they were not as encouraged about the success of the project.”

While they were sorely disappointed, as they had been counting on getting the NEH grant, all was not lost. Nakatomi reached out to fellow Southern Californian Paul Terasaki, a former surgeon whose tissue-typing technology for organ transplantations made him a multimillionaire — and a philanthropist.

“Fortunately for us, Norman Mineta has a very wide network of admirers and people who deeply respect him, and Dr. and Mrs. Terasaki were among them,” Nakatomi said. “We had a meeting, and it resulted in their very wholehearted support of the project.”

Not only were they supportive of the film, they also were supportive of the educational curriculum that accompanies it. (Editor’s note: Dr. Paul Terasaki died in 2016.)

The Terasaki Family Foundation’s support was important not just for the financial fuel it provided to help pay for the Mineta documentary and educational curriculum — it also gave legitimacy and confidence for other donors to follow suit, such as the Toshizo Watanabe Foundation and the Sachiko Kuno Foundation.

The funding upped the game for the production and helped pay for a touching sequence where the team followed Mineta on his visit to his familial hometown of Mishima, Japan, to visit relatives and pay his respects to his ancestors.

Part of Mineta’s legacy as an American politician, of course, was serving in Congress during the 1970s and ’80s as the issue of redress for the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans churned.

“In April of 1979, the national staff of JACL and its national officers came to D.C. to speak to the four Asian American members of Congress, namely [Sens.] Dan Inouye, Spark Matsunaga, Congressman Bob Matsui and myself,” recalled Mineta.

This was following the JACL’s most-recent National Convention at which a resolution was passed calling for legislative action for a national apology and redress payments of $25,000 per person to those directly affected by Executive Order 9066.

“Dan said, ‘Man, that’s a tall order,’” Mineta told the Pacific Citizen, adding that Inouye went on to suggest that what was needed was a Congressional commission to examine what had motivated the U.S. government’s WWII treatment of mainland Japanese Americans and legal permanent residents of Japanese ancestry who at the time were barred from becoming naturalized U.S. citizens.

Inouye didn’t think it was possible without such a commission, which was inspired by similar panels that investigated the assassination of President John F. Kennedy and the National Guard’s shooting deaths of four Kent State students.

Matsunaga told Mineta and the others that he already had a bill on native Hawaiian claims. It was given to Mineta’s legislative assistant, Glenn Roberts, who used it as a template, and with appropriate changes, it became the bill that President Jimmy Carter enacted to form the Commission on Wartime Incarceration and Internment of Civilians.

The CWRIC’s conclusion that the forced removal from the West Coast of ethnic Japanese and their subsequent incarceration was the result of war hysteria, race prejudice and the failure of political leadership, which would become the foundation of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which President Ronald Reagan enacted in the final months of his second term in office. The bill itself, which Mineta named H.R. 442, would have to be introduced several times before it finally found success.

While the Act apologized to Japanese Americans and paid those still alive $20,000 apiece, Mineta said in the documentary that the legislation wasn’t ultimately about Japanese Americans — it was about all Americans, the Constitution and what it means to be a U.S. citizen.

Mineta told the Pacific Citizen that another important piece of legislation that he was involved in was authoring the first rewrite of President Dwight Eisenhower’s 1956 National Interstate and Defense Highways Act. That rewrite, then known as the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act, aka ISTEA (dubbed Ice Tea), was signed into law by President H. W. Bush in 1991.

“It was considered landmark legislation,” Mineta said, “because highway bills had always been about automobiles and highways. … It was the first time there was a break from the traditional highway bill.”

Other legislation that Mineta was proud to be a part of was the Americans With Disabilities Act of 1991, of which he was one of the four original sponsors.

“I wrote the transportation piece of the ADA,” he said. Mineta also chaired the House Committee on Public Works and Transportation.

Transportation was and is an area where Mineta, who shared that he now drives a battery-powered Tesla and only starts up his internal combustion engine care occasionally to keep its battery from dying, has much expertise.

He served as the Secretary of Transportation under President George W. Bush from 2001-06 as the sole Democratic Cabinet member in a Republican administration. It was a post that Bush’s predecessor, President Bill Clinton had years earlier offered to Mineta, but had declined.

“I said no because my brass ring had always been to become the chairman of the House Committee on Public Works and Transportation,” Mineta said, recalling his conversation with Clinton after he was first elected in 1992. “As much as I appreciate it, I’m going to bypass this opportunity to be Secretary of Transportation in your administration.”

Later, however, in 2000, when Mineta was working for Lockheed Martin, Clinton’s camp again reached out to Mineta to become Secretary of Commerce when Bill Daley resigned to run the presidential bid of Vice President Al Gore. This time, Mineta said yes, and he held the position from May 2000-Jan. 17, 2001.

Then, in late December 2000, before the inauguration of President George W. Bush, he received a called from Vice President-elect Dick Cheney, who offered him the post of Secretary of Transportation. Mineta had to mull it over, as he didn’t want to be “marginalized as the only Democrat in a Republican administration — and on the other hand, I don’t want to be considered a turncoat by the Democrats.”

After conferring with more than 100 people, including President Clinton, he decided to take the job. Mineta’s presence in the Bush Cabinet, after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, would serve to mitigate calls for a blanket round up of Muslims and people of Middle Eastern ancestry living in the U.S.

In addition to interviews with Clinton and Bush, “An American Story: Norman Mineta and His Legacy” also contains interviews with childhood pal and former Republican senator from Wyoming Alan Simpson, ex-wife May Mineta and former Rep. Dan Lungren, who was an opponent of redress.

For the filmmakers, the documentary is only a part of passing on Mineta’s legacy, since an educational curriculum based on his career and achievements was baked into the project from the beginning, covering six modules — immigration, social equity and justice, reconciliation, leadership, U.S.-Japan relations and civic engagement — and with completion set for the fall.

“A lot of times, the curriculum is sort of an offshoot of the film,” said Fukami. “We wanted to approach it totally differently.”

Working in tandem with Stanford University, as they conducted interviews for the film, they also did interviews specifically for the curriculum.

“When we interviewed President George W. Bush or President Clinton, we had separate sets of questions that would be targeted for the curriculum’s lesson plans,” said Fukami.

It will be offered free, available on the website MinetaLegacyProject.com, in the coming months.

With their documentary now ready to air nationally on May 20, Fukami and Nakatomi have no set plans for whatever their next project may be.

“I don’t know about Debra. I need a rest!” said Fukami. “This has been an obsession. I’m tired.”

Nakatomi noted that they weren’t just hired guns to make a documentary.

“We are personally invested,” she said. “We have deep connections with the community, and we really care about how Norm’s story is told. When I was in Denton, Texas, a couple of weeks ago, I was amazed at how personally connected people felt to the Japanese American story and what is happening today with immigrants.”

The first interview they shot for the movie was in 2013, which means they have been working on the project for more than five years, while also chasing down funds and working their respective day jobs.

For Fukami, that means running her own production company and teaching TV and video production at Academy of Art University in San Francisco. For Nakatomi, that means running her communications company, Nakatomi & Associates in Los Angeles.

“For the longest time, it was just Debra and me. For the last two years or so, we’ve been able to persuade Amy Watanabe to work with us as an associate producer, and I kiddingly call her our boss because she sort of whipped us into shape and takes care of our logistics,” Fukami said. “She’s been invaluable.”

“It took over our lives,” said Nakatomi, who noted that they began the Mineta documentary while still working on “Stories From Tohoku.”

But they also knew the importance of telling Mineta’s story, especially after the 2016 presidential election.

“Things dramatically changed, and all of a sudden, the things that Norm stood for — personal integrity, leadership, bipartisanship, political civility — those all started to become important values that people were hungering for, so Norm’s story and what he stood for became much more significant and relevant in a way we could not have anticipated,” said Nakatomi.

“Every time we watch the film, we still cry,” laughed Fukami. Waxing serious, she added: “We’re hoping that the takeaway for the audience that sees the film is inspiration by Norm’s life — that they realize that one man can make a difference, and it causes them to reflect a little bit about their own personal philosophies about immigration or prejudice or political civility, civic engagement. ‘What can you do to make this country a better place,’ just on an individual basis.”