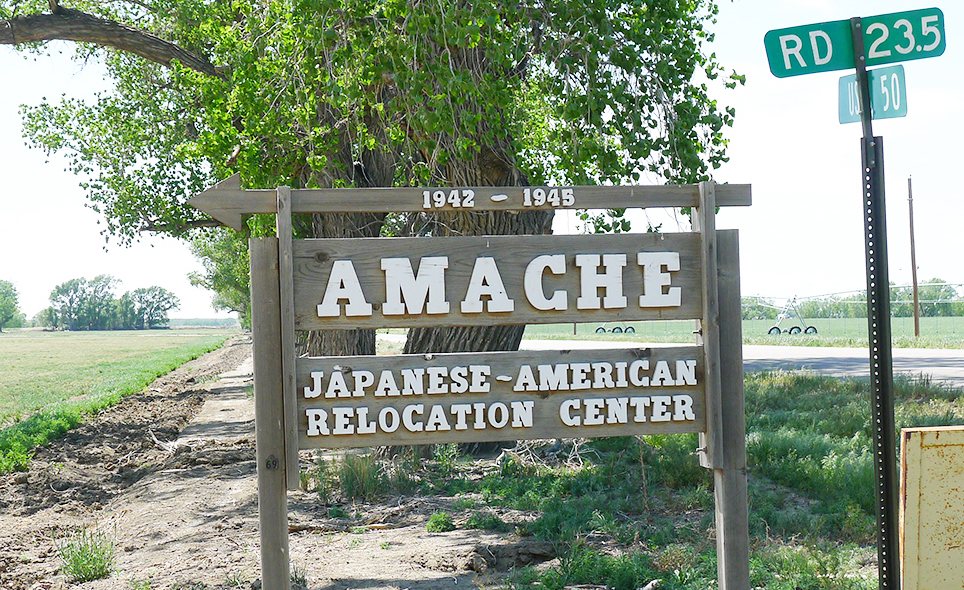

It’s official: Camp Amache in February received status as an national historic site and will now be under the jurisdiction of the National Parks Service. (Photo: Gil Asakawa)

Official designation for Colorado concentration will help prevent erasure of history.

By Gil Asakawa, P.C. Contributor

(Editor’s note: Nearly two years after President Joe Biden signed the Amache National Historic Site Act, which designated the Amache site as part of the National Park System, Interior Secretary Deb Halland on Feb. 15 formally established the Granada War Relocation Authority Center, aka Camp Amache, as the Amache National Historic Site. Amache, which during World War II incarcerated 7,318 ethnic Japanese, most of whom were U.S. citizens near the town of Granada, Colo., was one of the 10 American concentration camps operated by the federal government’s War Relocation Authority.

In a statement, Halland said, “As a nation, we must face the wrongs of our past in order to build a more just and equitable future. The Interior Department has the tremendous honor of stewarding America’s public lands and natural and cultural resources to tell a complete and honest story of our nation’s history. Today’s establishment of the Amache National Historic Site will help preserve and honor this important and painful chapter in our nation’s story for future generations.”

The following article elaborates on the path to this status and provides background about Japanese American pilgrimages to the site and how the local Colorado community has embraced its role in preserving the site for historical purposes.)

The first pilgrimage to Amache, one of the 10 Japanese American incarceration camps on the U.S. mainland and the only one located in Colorado, was held in 1975. This year, almost 50 years later, the pilgrimage will hold special significance: In February, Amache officially became a National Historic Site, part of the National Park Service system alongside Manzanar in California, Minidoka in Idaho and Honouliuli in Hawaii.

The bipartisan legislation that cleared the way for the park status, sponsored by Colorado Congressmen Ken Buck, a Republican, and Joe Neguse, a Democrat, was passed in the House in 2021 and then led through the upper chamber by Colorado Sens. John Hickenlooper and Michael Benett. It was signed into law by President Biden in 2022. But it didn’t become official until after the town of Granada, Colo., worked out details (water rights, etc.) with the National Park Service and signed over the deed to the land outside of town.

President Joe Biden (center) signs the Amache National Historic Site Act on March 18, 2022, to put Camp Amache under the National Parks Service. (Photo: The White House)

The site was named Amache after WWII — the government’s official euphemism for it was the Granada War Relocation Authority Center — and the camp was dubbed Amache, after an indigenous woman who helped build bridges between Native Americans and their white oppressors.

It’s been a long, slow road to official park status. Amache was listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places in 1994, named one of Colorado’s most endangered sites in 2001, then designated a National Historic Landmark in 2006. These designations helped give the site a bigger national profile, but the federal support as a National Park site will bring resources beyond the community-led efforts that have funded the site for decades.

The Japanese American community, including Amache survivors and descendants from across the country, but mostly in California and Colorado, hold pilgrimages to far southeast Colorado (a four-hour drive from Denver) site on the weekend before Memorial Day weekend.

Min Tonai, who was incarcerated at Colorado’s Camp Amache, addresses pilgrims in May 2018 via a bullhorn held aloft by John Hopper, a local social studies teacher who has incorporated the history of the site in his curriculum. (Photo: Gil Asakawa)

John Hopper, a social studies teacher hired at the town’s K-12 Granada School, learned about Amache while growing up about 60 miles away. His mother was friends with a survivor who told Hopper about Amache. When he was hired to teach in Granada, he saw an opportunity to engage students in living history right outside of town. The students from that class, and each subsequent year’s classes, eventually formed the Amache Preservation Society and have taught about its history in public presentations not just in the area, but in neighboring schools and states.

The Granada students even opened a museum in a donated home a block from their school and jampacked it with artifacts and displays they created for talks they give across the region and over multiple states. Each year, a new crop of dedicated students sign up for the class – Hopper is today the dean of students at the school and still teaches the Amache class and heads the Preservation Society. One of his students even teaches history today at the school, and Hopper expects he could take over when he retires. Hopper was even given a special commendation by the Consul General of Japan at Denver in 2014 for his tireless work.

In a very Japanese-like aw-shucks way, Hopper, who also served on the town council while teaching and running the Amache efforts, deflects his accomplishments and praises “all the great students over the years that kept me going,” he said. “Let’s just put it that way.”

In all the years he has worked on preserving Amache and keeping its legacy alive with generations of students, Hopper says he didn’t imagine a day that the camp would become a national park.

“No, no, no, not even close,” he insisted. “You know, I thought, ‘Oh, no.’ I mean, I’ll be honest with you. When I started this thing, I didn’t think we’d have a brand-new museum. Yeah. I’m getting ready to order thousands of dollars of brand-new display cases and stuff. I didn’t ever believe this ever, ever. No, never.”

Exterior of the Amache Museum in Granada, Colo. (Photo: John Hopper)

The Amache Preservation Society opened a tiny, crowded museum in an old house a block from the school some years back to display artifacts and photos donated by survivors, as well as models of the camp created by the students. In 2019, a bank donated its building across the street from the school as a newer, bigger museum.

Hopper and the APS have diligently funded all their volunteer work and equipment for maintaining Amache and the museum through donations from the community including JA and non-JA, civic organizations, grants from preservation organizations. That needs to continue even after the NPS sets up the site because the museum is not part of the National Historic Site, and the NPS doesn’t display artifacts (it stores artifacts at a site in Arizona). So, Hopper will continue to maintain the museum site separate from the nearby national park.

The students have had one steadfast partner for the long run, the Denver Central Optimists Club, whose core members were Japanese American incarceration survivors dedicated to preserving the history of their experience.

Derek Okubo, who served as the executive director of the City of Denver’s Agency for Human Rights and Community Partnerships (the modern iteration of the agency that legendary Nisei attorney Min Yasui ran for decades), is the son of Hank Okubo, who as a child was incarcerated at Amache.

Hank Okubo was one of the founders of the Denver Central Optimists Club in 1983, which organized each year’s pilgrimages, worked to clean and preserve the camp and raised money to erect a stone memorial at the camp’s cemetery to all the incarcerees and the men who left Amache to join the U.S. military.

Monument to Japanese Americans from Amache who lost their lives in WWII after volunteering to serve in the Armed Forces, as well as those who died in the camp while incarcerated (Photo: Gil Asakawa)

Once Hopper got involved with Amache, he met and worked with the Optimists Club and coordinated the cleanup, preservation of the site and reconstructions of a guard tower, a water tower and, most recently, an entire barrack, as well as the restoration of a rec center building that had been used for decades by the town of Granada as a storage shed for equipment in a town park.

One of the keys to Amache being named a national park has been the support from the community, both in Granada itself but also in Denver and across the country. All the individuals, organizations and institutions that have worked to preserve the camp show that the site is deserving of its designation, says Tracy Coppola of the National Parks Conservation Assn., a nonpartisan nonprofit that worked with the NPS to shepherd Amache’s progress and lobby Congress on its behalf.

“Amache is really like the example in my heart of an opportunity to connect with living history, the hearts of people who were at Amache and their descendants and all of the various perspectives about why this park is important. We saw early on the foundation that the stakeholders and the descendants had really laid to make the voice not be forgotten, you know, and really without that, I don’t think it would have been nearly as powerful a campaign.”

Rob Buscher, executive director of the Japanese American Confinement Sites Consortium (and a former Pacific Citizen editorial board chair), agrees. “I think it’s a really great development for this site, specifically because it’s something that a lot of the descendants and survivors have been working toward for a long time,” he said.

“I think the nature of the local partnerships here are really encouraging to see, as well as the local residents of Granada and Lamar, who have been really supportive of the historic preservation in the decades leading up to this moment.”

Archeologist Bonnie Clark, seen in this 2014 photo, points out an object on the site of the Amache concentration camp. (Photo: Gil Asakawa)

One of Amache’s many stakeholders is Bonnie Clark, a professor of archaeology at the University of Denver, who read an Archeological Survey report about Amache in 2003 that had been funded by the Optimists Club. “There were like two things about the report that struck me,” she said. “One was just that the findings were amazing to me. And, then it was the fact that the community had supported the archeological study.”

The same community involvement and passion eventually helped spark the national park designation. In 2005, Clark met Hopper in Amache, and in 2006, she began to take students every other summer on an archaeological dig to collect artifacts. Over the years, she has accumulated a large collection of everything from toys and tools to ceramics, and she has displayed them at the university’s museum and created a traveling exhibit of images of objects from Amache with text from community members about the items.

It’s one way that shows the legacy Amache has had far outside of the corner of Colorado where more than 7,000 Japanese Americans were imprisoned during WWII.

Derek Okubo is especially looking forward to this year’s pilgrimage to Amache in May because he knows his father would have cheered the day. “It’s pretty amazing, actually, because I remember that it was a dream of my dad’s, and you know, he knew it was going to be a long-term effort.

“And so, to finally say it happened is pretty amazing,” he added. He only regrets that the other founders of the Denver Central Optimists Club and many leaders of other organizations that helped achieve the park status aren’t here to celebrate.

“It was something that he and all these guys who were really the ones who started it all wanted to happen, and they never lived to be able to see it.”

They’ll be smiling from wherever they are, though.

(The next Amache Pilgrimage is scheduled for May 17-19. To learn more about the Amache Preservation Society, visit amache.org/amache-preservation-society/.)

This article was made possible by the Harry K. Honda Memorial Journalism Fund, which was established by JACL Redress Strategist Grant Ujifusa.

New Amache National Parks Service sign, March 2023. (Photo: Chris Mather)