Matsumoto mulls the modern muddled mess of mindfulness.

By P.C. Staff

Can something once confined to an ethnic culture that crosses over and finds mass acceptance lose its roots and original meaning?

When an idea or concept once associated with a particular community undergoes commodification by the greater community, should that automatically be viewed askance?

Is it “cultural appropriation” when a practice that was associated with a subculture is adopted by the masses?

Is it “cultural appropriation” when a practice that was associated with a subculture is adopted by the masses?

Those questions and others could have been the larger and unasked subtext to the virtual panel titled “When Healing Is Home: The Japanese American Roots of Mindfulness and Community Care,” which took place on July 16 at the 2021 JACL National Convention and was hosted by the JACL’s National Youth/Student Council.

Mariko Rooks, NY/SC representative for the JACL’s Eastern District Council, serving as the panel’s facilitator, introduced the panel’s main speaker and presenter, Devon Matsumoto.

Rooks emphasized that Matsumoto would discuss the Japanese and Japanese American roots of “practices that might seem trendy” and “really understanding … what that history is and how that affects our present and … how that relates to our identities here today.”

In her introduction, Rooks described Matsumoto as a San Francisco Bay-area denizen who resides on “unceded Ohlone land” and works in juvenile justice, having earned a master’s in social work from Seattle University and whose organizing work “focuses on understanding the complexities of Asian American Buddhist identity.”

Devon Matsumoto (right) and Mariko Rooks explored the topic of “mindfulness” during the NY/SC’s plenary presentation at the recent JACL National Convention.

“Of course, at JACL, we are nondenominational, and we understand that a lot of different religions play a really important part in our community’s identity, but Devon will be talking a little bit about some specific practices that originate from some specific parts of our community that hopefully can still be applicable to everyone,” Rooks added.

Matsumoto began with a land acknowledgement that he lives on Ohlone and Mukwekna nations’ land — and noted that it also was an acknowledgement that a land acknowledgement was “not enough” — but it was nevertheless a form of mindfulness, which was the part of the panel’s title.

In that spirit, Matsumoto then led a grounding exercise that included breathing, relaxation, visualization and listening. This, too, was a real-world example of a practice of mindfulness, a term that has gained mainstream popularity in recent years and therefore has definitions that have, despite its Buddhist roots, morphed to mean different things to different people, groups and even corporations that might offer mindfulness sessions after “80-hour work week” to squeeze even more productivity from workers.

“How does mindfulness and caring relate to community care? Or does mindfulness even relate to caring at all?” asked Matsumoto. “For me, I like to quote Mitsuye Sugino, who is a leading Buddhist teacher, anti-racist teacher as well, who really looks to see the roots of mindfulness within Asian communities and within Buddhist Asian communities.

“And so, what she talks about is that ‘mindfulness becomes not a strategy to alleviate suffering but an exercise in complacency, of turning away from ethical questions,’ and that ‘capitalism co-opts questions of racial justice and reformulates them as aesthetic cultural productions.’”

Matsumoto added that in the Buddhist origins of mindfulness practice, the purpose was “to seek out the causes of suffering and to alleviate them.”

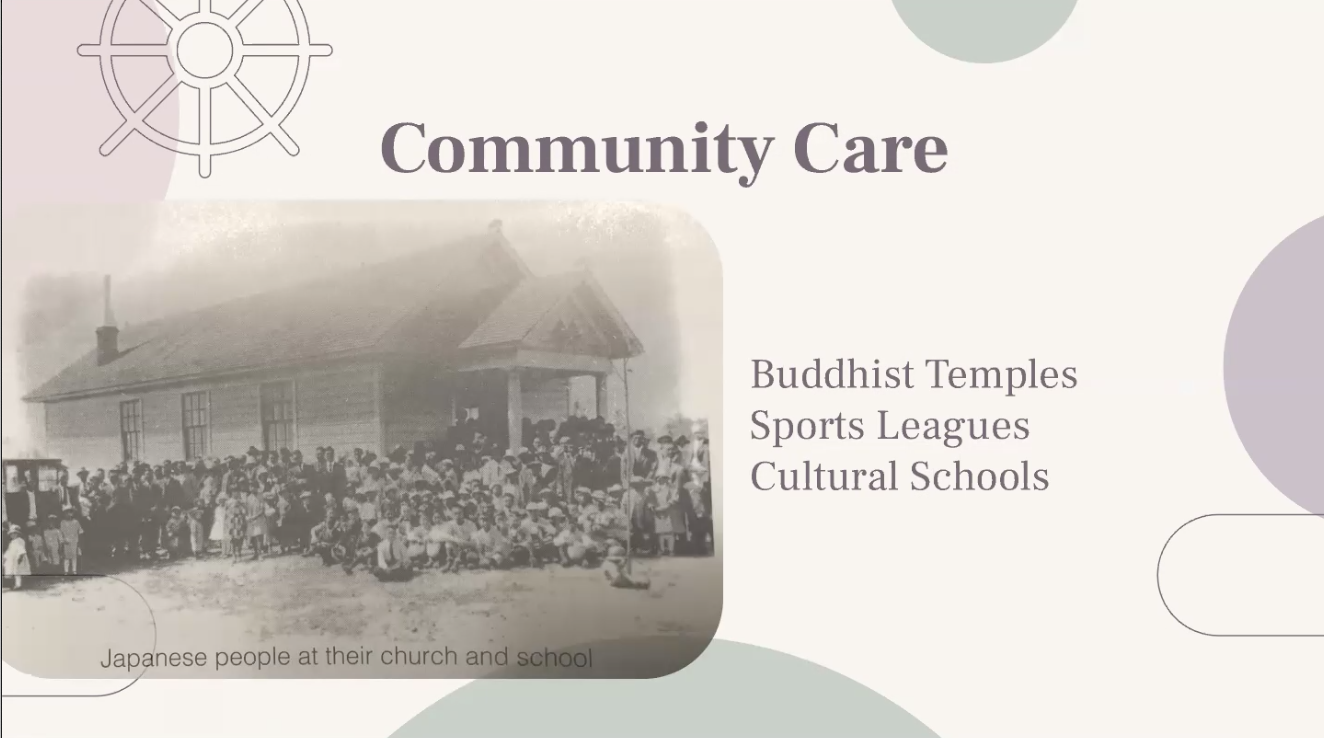

Turning his eye to the Japanese American communities, “community care” was what led to the formation of Buddhist temples and Japanese American Christian churches, not to mention sports leagues and cultural schools that were reactions to racial and religious discrimination, and white supremacy on American shores.

These groups provided mutual aid in the form of food drives, blood drives and pooling of monies to help those within the Japanese American community, Matsumoto said, and today, these institutions can “still act as places of refuge” even 100 years later in the form of anti-Asian violence that has resurged under the Covid pandemic.

These groups provided mutual aid in the form of food drives, blood drives and pooling of monies to help those within the Japanese American community, Matsumoto said, and today, these institutions can “still act as places of refuge” even 100 years later in the form of anti-Asian violence that has resurged under the Covid pandemic.

Although some practices from the Japanese American community have had crossover success, Matsumoto asked Rooks to read a slide that indicated how some healing practices that haven’t been accepted outside the community get labeled as “uncivilized,” “superstitious” or “unscientific” when they can’t be measured or monetized.

Using the chat function, audience members gave examples such as “mochitsuki,” “acupuncture,” “anything Zen,” “obon dance,” “obutsudan” and “chanting.” For Matsumoto, he looked at taiko “as a cultural tool” and a “form of resistance” with therapeutic applications for generations.

“However, it was not until recently that the use of taiko has become more and more accepted as an alternative form of therapy because of the growing interest in it from white therapists and white clients seeking its benefits. So, like mindfulness practice, this often leads us to the separating of taiko from the Japanese American experience and the erasure of Japanese American activists, like Rev. Mas Kodani, who are credited with beginning the taiko movement here in the United States,” Matsumoto said.

Matsumoto wrapped up his presentation by throwing to Rooks, who read a passage by Aaron Lee (“Angry Asian Buddhist” blog), who died in 2017 and was quoted by Chenxing Han in her book “Be the Refuge: Raising the Voices of Asian American Buddhists”:

“There is a temptation to strive to change what’s outside, rather than focus on ourselves and our own communities. While we still need to articulate our principles, relay our stories, protest injustice and cast our votes, we are most compelling when we are the very refuges we wish to see in this world.”