“Night in the American Village: Women in the Shadow of the U.S. Military Bases in Okinawa” and “Let the Samurai Be Your Guide: The Seven Bushido Pathways to Personal Success”

Books and more make this the best time ever to be stuck at home.

By P.C. Staff

As the world churns with fear, uncertainty, self-quarantining, physical distancing, shortages, economic havoc, illness and even death itself, inflicted by the exponential spread of the novel coronavirus and the consequences of actions (and inactions) by our political leaders, most of us have become unfamiliarly and disconcertingly homebound.

No joke: The news is grim for those on respirators due to COVID-19, exhausting for those tasked with caring for them, tragic for those who have lost loved ones to the virus, unsettling for those facing financial hardship or ruin, scary for those either with compromised immune systems or having relatives in those circumstances — and just plain stressful overall.

‘In all of history, has there ever been a better time to be homebound?’

There are, however, some upsides for us all: For example, air quality in cities like Los Angeles has improved thanks to fewer cars, buses and trucks on the roads. If you’re still employed, the drive to work has either become nonexistent thanks to telecommuting or manageable — pleasurable, even — with so few others driving.

At stores and supermarkets, milk, eggs and rice (and toilet paper, of course) have reappeared, now that the supply lines have caught up to the panic-buying hoarders who depleted shelves early on.

As for the quotidian stress caused by being obligated to attend in person at (or deliver someone to) this or that meeting, fundraising dinner, sporting event, recital, party, convention, sales call, botox appointment, music lesson, tutoring session or what have you — well, it’s all been canceled or postponed. Is that so bad?

For the significant numbers of those fortunate to have good health, a roof overhead with space enough to not be cheek by jowl with others of questionable hygiene and (hopefully) with semisecure finances, here is a question: In all of history, has there ever been a better time to be homebound?

Seriously, in pandemic-era America, you can still have all the old standbys for one-way and two-way communication with the world outside your bunker, uh, home: a daily general-interest newspaper, magazines, radio, television (terrestrial or cable) and the telephone. (Keep in mind that an honest-to-goodness newspaper subscription confers other benefits that getting the news on a smartphone or tablet simply cannot duplicate. See toilet paper shortage, above.)

If you have broadband Internet connectivity and a computer, smartphone or tablet, add email as a means for communication and meetings, FaceTime, Skype and everyone’s new friend, Zoom. In small doses, there is also social media, be it Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snap, TikTok, etc.

Meantime, gamers with a console or gaming computer can either play solo or interact with others via multiplayer games. Also if you have broadband, there are streaming services for music (Apple Music, Amazon Prime Music, Spotify, Pandora) and TV shows and movies (Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, Hulu, Apple TV+, Disney+, CBS All Access).

Meantime, gamers with a console or gaming computer can either play solo or interact with others via multiplayer games. Also if you have broadband, there are streaming services for music (Apple Music, Amazon Prime Music, Spotify, Pandora) and TV shows and movies (Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, Hulu, Apple TV+, Disney+, CBS All Access).

Many of the aforementioned are now offering free trials. And we can’t forget that relative newcomer to the media menu, the podcast, of which there are now thousands to choose from for your listening pleasure.

Unlike just a few years ago, there’s no need to visit a bricks-and-mortar store; these services and the stuff they offer come directly to your home’s hi-fi, big-screen TV or handheld device. Unlike a just few weeks ago, there are even first-run motion pictures that you can now pay to watch at home, too, now that movie theaters are shuttered.

You may in these times be scared, but there is no excuse to be bored. Apologies to Rod Serling, but you can be like the book-loving Henry Bemis character in the episode of “The Twilight Zone” titled “Time Enough at Last” — only with eyeglasses intact.

That’s an appropriate reference because thus far, there’s been no mention of books. Yes, that standby from the olden days: printed symbols in black ink on bound sheets of bleached-white wood pulp — or the digital simulation of that experience known as the e-book reader.

Like to read? Then now is your time because while your local library may have closed its doors, Amazon still, as of this writing, delivers. (Just be sure to first visit PacificCitizen.org and click on the Amazon link!) And, you can also search for an independent bookseller that can mail you a book.

The following article features two authors and their books: Akemi Johnson, author of “Night in the American Village: Women in the Shadow of the U.S. Military Bases in Okinawa” (ISBN-13: 9781620973318, The New Press, 224 pages, © 2019, SRP $28) and Lori Tsugawa Whaley, author of “Let the Samurai Be Your Guide: The Seven Bushido Pathways to Personal Success” (ISBN: 9784805315385, Tuttle Publishing, 192 pages, © 2020, SRP $17).

‘Night in the American Village’

“It’s complicated.”

Those words might be the best way to describe the stories and relationships detailed in the oft-times contradictory, confounding and even condemnable situations and circumstances described in Akemi Johnson’s 2019 book “Night in the American Village: Women in the Shadow of the U.S. Military Bases in Okinawa.”

While the book’s subtitle reveals that Okinawa Prefecture is the location, what may be less known is American Village, which refers to an attraction in Chatan, an area southwest of Kadena Air Base, the largest U.S. Air Force base in East Asia.

While the book’s subtitle reveals that Okinawa Prefecture is the location, what may be less known is American Village, which refers to an attraction in Chatan, an area southwest of Kadena Air Base, the largest U.S. Air Force base in East Asia.

With its signature Ferris wheel, American Village is a destination where tourists, locals and military personnel can shop, dine and mingle in a setting inspired by American culture, which already pervades Okinawa in a manner beyond any other place in Japan, thanks to an enormous, decades-long U.S. military presence on a relatively small island.

It’s also one of the places where, once the sun sets on the East China Sea, American military men — and the word “men” is used instead of “personnel” on purpose — and those Okinawan women known locally as amejo or women who seek, for a variety of reasons described in the book, relationships with American men stationed on “the Rock,” can hook up.

With moderator Professor Lilly Anne Welty Tamai, the Sacramento-based Johnson discussed her book on Jan. 25 in Little Tokyo at the Japanese American National Museum’s Tateuchi Democracy Forum.

Lilly Anne Welty Tamai (left) interviews Akemi Johnson, author of “Night in the American Village” at the Japanese American National Museum’s Tateuchi Democracy Forum in Little Tokyo on Jan. 25. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Because of that aforementioned lengthy U.S. military presence on Okinawa that dates to Japan’s defeat at the end of World War II, chances are pretty good you may know of someone — be it an older acquaintance or relative who served in the military and was stationed or visited there, be it the Korean War era, Vietnam War era or more recently. And, most of those connected in some way to the military who spent time on Okinawa remember it fondly.

The reasons are many. With its semitropical flora and fauna, ocean vistas, scenic beaches and usually friendly populace, Okinawa, its culture and lifestyle are unlike the main islands of Japan.

That difference is what led Johnson, who describes herself as a mixed-race Yonsei with a Sansei mother, Nadine Narita, with familial roots in Hiroshima, and a white American father, Nick Johnson, who was not military, to connect to Okinawa during a one-week visit there in a way she did not in Kyoto, where she spent a year of college.

“I think it’s about me having this mix of cultures and the intertwined history with Japan and the United States and kind of feeling like an outsider in Japan,” Johnson told the Pacific Citizen. “I could identify with a lot of that. I recognized something in Okinawa that resonated with me personally, and it felt very important to me to figure it out. Once I started, I couldn’t stop.”

That connection to Okinawa, felt by the Oakland, Calif.-born Johnson, an eldest child with a younger sister and brother, may have come from growing up Hapa in NorCal’s Santa Cruz and Marin County. Most of her peers at that formative age were white, but with a Japanese first name and Eurasian features, she didn’t quite fit in.

Even as Johnson would later connect to her Japanese heritage by spending a year studying in Kyoto, her exposure to Okinawa during that time led to her seek a Fulbright grant that allowed her to spend another year there and focus on what would become her book.

During the JANM event, Johnson said the process of writing the book took more than 15 years, including a sidetrack in which an earlier version had to be scrapped because the person she initially focused on — a woman from Tokyo who moved to Okinawa — decided she no longer wanted to written about.

Akemi Johnson chats with Renée Liu following a moderated discussion about her book, “Night in the American Village.” (Photo: George Toshio Johnston

But as a woman, Johnson still wanted to focus on the untold story of the local women and their varying relationships with the servicemen — these days more Marine Corps and Air Force than Army or Navy — stationed on Okinawa.

But she had no interest in “destructive, racist stereotypes” dating back to Madame Butterfly. “I wanted to put women at the center of this and show real women’s stories that are really nothing like those caricatures that we might have heard about in the U.S.,” she said.

Added Johnson: “I wanted to move beyond the victim story as well, even though that is really important, the story of sexual assault. It’s a giant problem that we cannot overlook.”

Worth noting is that sex crimes perpetrated by servicemen go back to the earliest days of the American presence in Japan and Okinawa, with a pair of more contemporary incidents gaining worldwide notoriety, namely the gang rape of a 12-year-old girl in 1995 by a sailor and two Marines, and the rape and murder by a former Marine civilian of 20-year-old Rina Shimabukuro in 2016, both on Okinawa.

Because sexual assaults overall across Japan are reported to the police at a lower percentage than in the U.S., Johnson said that some servicemen have cited that statistic as a reason why they committed those crimes — because they thought they could get away with it.

Nevertheless, Johnson wanted to focus on women who were “using the situation to get something that they want and for a lot of times that was expressing themselves in a more ‘American’ way, being more outspoken, caring less what others thought about them, dressing the way they wanted to dress.”

In “Night in the American Village,” each chapter is about a different woman and how they each connect and relate to Okinawa’s outsize American military presence and Americans, based on their individual backgrounds and desires.

During her research, Johnson also discovered that Okinawa, with its mix of indigenous, Japanese and American cultures, provided a rare intersection in the world where she felt freed from expectations of race and nationality. From her perspective, Okinawa was a “unique space” for mixed-race people and international families that stay there because Okinawa has become their home.

“It’s perfectly their world,” she said, and while she is in favor of what the Okinawan people want, namely a reduced American military presence, that would probably also affect those people and families. “There are more of those people than you might imagine.”

Regarding that elusive reduction in the American military presence, Johnson learned that that issue is also complicated. There is definitely a vocal faction of Okinawans and mainland Japanese living in Okinawa of the “Yankee Go Home” tribe.

There are also, however, those who, having grown up knowing nothing else but having American bases and military personnel around, with fighter jets, cargo planes and helicopters constantly overhead, seem to be OK with the status quo, especially for those Okinawans with American friends or relatives.

There is also the economic factor: The many bases are still a part of the economy of Okinawa, usually among Japan’s poorest of prefectures, even as tourism from mainland Japan, China, South Korea and Taiwan has grown.

Looming larger, of course, is geopolitics. Before Okinawa’s 1972 reversion to Tokyo’s control, the United States served as the island’s governmental authority and issued license plates that had the slogan “Keystone of the Pacific.”

Going back before it had evolved into an independent kingdom that was a hub for regional trade, what is now Okinawa Prefecture remains located strategically within the range of Taiwan to the south, Japan to the north — and to the west and northwest, the People’s Republic of China and the Koreas.

Prereversion license plate for Okinawa.

Okinawa remains the Keystone of the Pacific, and keeping China and North Korea in check is still a big priority for the United States, Japan and South Korea. America’s multidecade military presence, with its inherent pluses and minuses, doesn’t appear to be going anywhere soon.

If, however, as geopolitical analyst Peter Zeihan (“Disunited Nations: The Scramble for Power in an Ungoverned World”) believes, the U.S. should continue to reduce its global footprint and overseas military bases, will Okinawa’s “Yankee Go Home” faction finally get its wish? And is that desirable? Only time will tell.

But as the 2020 coronavirus pandemic has proven, great change can come quickly and unexpectedly, and the future of the shotgun marriage (Maybe “machine gun marriage” is more accurate?) between Okinawa and America won’t be found in “Night in the American Village,” Johnson’s first book.

At JANM, Johnson did say that there will be a translated version in Japanese due later this year, and via an email, she told the P.C. that it will be “interesting” to see the reaction to her book in Japan and, of course, Okinawa.

As for what might be next, Johnson said that aforementioned pandemic has put thoughts of a future book on hold, as she and her husband, Rei Onishi, hunker down at home with their 1-year-old daughter.

“I want to write something about the WWII Japanese American incarceration and have been contemplating the right approach or angle,” she wrote via email.

While writing about that subject matter may prove to be as “complicated” as that contained in “Night in the American Village,” Johnson has definitely proven herself to be up to that task.

‘Let the Samurai Be Your Guide’

It’d be a safe bet that many Americans of Japanese heritage believe — or would like to believe — that their ancestors were bushi, Japan’s world-famous samurai or warrior caste.

It’d be a safer bet, however, that in actuality, more Americans of Japanese heritage had ancestors who were farmers and fishermen, with some smattering of artisans, merchants and other groups — not that there’s anything wrong with that. Regardless of class, some of those Japanese who felt compelled to leave for better opportunities elsewhere became today’s Japanese Americans.

In the case of Lori Tsugawa Whaley, a Washington State-based Sansei, public speaker and life coach, she can actually claim samurai heritage through her father’s side of her family, and she believes that the teachings of Japan’s warrior code, bushidō, is ingrained into Japanese culture and therefore lives on among Japanese Americans — and can be beneficial to anyone on the path of self-improvement.

The daughter of George Tsugawa, 98, and the late Mabel Tsugawa, Whaley believes that regardless of one’s ancestor’s caste, Japanese Americans were imbued with the teachings of bushidō by their Issei and Nisei forebears — and honors that in her book, “Let the Samurai Be Your Guide: Seven Bushido Pathways to Personal Success.”

The daughter of George Tsugawa, 98, and the late Mabel Tsugawa, Whaley believes that regardless of one’s ancestor’s caste, Japanese Americans were imbued with the teachings of bushidō by their Issei and Nisei forebears — and honors that in her book, “Let the Samurai Be Your Guide: Seven Bushido Pathways to Personal Success.”

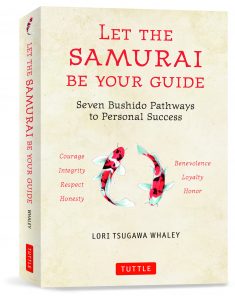

Released last month, “Let the Samurai Be Your Guide” identifies seven principles contained in bushidō: courage (yūki), integrity (gi), respect (rei), honesty (makoto), benevolence (jin), loyalty (chūgi) and honor (meiyo) and exemplifies each principle with a person or group that personify that trait.

While the trait of courage uses a Nihonjin, diplomat Chiune Sugihara, as its example, most of the other examples are actually Japanese American individuals, families or military units, such as Sen. Daniel Inouye, Michi Nishiura Weglyn, Dr. Toshio Inahara, the Moriguchi family of Seattle and the Military Intelligence Service and the 100th Battalion/442nd Regimental Combat Team.

One of six Tsugawa children, Whaley was born after WWII in the rural logging town of Woodland, Wash., which was mostly white. Even though her maternal grandmother instilled in her a love and awareness of Japanese culture as a child, growing up as she did led her to keep “Japanese things” at arm’s length, despite her family, face and last name.

“I grew up in the ’60s — not a great time to be Japanese,” Whaley said. By the time she attended college, she did, however, take a couple years of Japanese language. After graduating, she also landed a job at the Tacoma Art Museum as the assistant to the curator, Sara Little Turnbull, who became Whaley’s “Jewish mother.”

“I grew up in the ’60s — not a great time to be Japanese,” Whaley said. By the time she attended college, she did, however, take a couple years of Japanese language. After graduating, she also landed a job at the Tacoma Art Museum as the assistant to the curator, Sara Little Turnbull, who became Whaley’s “Jewish mother.”

As an admirer of Japanese culture, Turnbull urged Whaley to explore her Japanese roots, telling her she was more Japanese than she realized. In the book’s preface, she tells of a turning point that occurred for her in 1994: an exhibition at Seattle’s Wing Luke Museum on Sugihara, who was himself of samurai lineage.

Whaley was inspired by Sugihara’s selfless actions, in which he famously and at great personal cost to his career wrote thousands of transit visas for Lithuanian Jews fleeing Nazi persecution and death camps. (On a related note, she said that the government of Lithuania has declared the year 2020 to be the “Year of Sugihara,” who was born 120 years ago.)

The 2003 film “The Last Samurai” also resonated with her and led her to further embrace not only her Japanese heritage but also study what made the samurai, the Japanese people — and herself — tick.

Visiting Japan would also prove to be beneficial to Whaley’s journey of embracing her heritage.

“I felt like I was home. I did, I really did,” she laughed. “I just felt so comfortable. I thought, ‘Wow, these people look like me, act like me, think like me.’ I started understanding more of my Japanese roots, why I am the way I am.”

These life events would culminate in the first version of her book, which was self-published in 2015 and titled “The Courage of a Samurai.” When it was discovered by a representative of Tuttle Publishing — the famous Vermont-based publisher of books about Japan and Asia — the new version of the book became “Let the Samurai Be Your Guide.”

Whaley is happy with the result. “They are wonderful people to work with,” she said.

Worth noting is that Whaley includes a chapter about a principle that is not among the seven principles of bushidō, yet to her encapsulates the warrior’s code — and that is ganbaru, which defies direct translation into English but can mean perseverance, tenacity, determination, do your best — even go for broke.

That principle was one that Whaley had to personally draw upon because she had the misfortune of being in not one but two car accidents; the first was more physically debilitating, but the second one resulted in a traumatic brain injury.

“I just knew something was different after it happened,” Whaley said. Her speech and reading were affected. “I wasn’t able to think and concentrate. I went through a lot of therapy, especially with speech pathology. I did that,

I saw chiropractors, neurologists, you name it, and I was there, trying to get better.”

The TBI also left her with auditory processing deficit, which meant she was unable to process information she heard as well as she used to. While she could follow written instructions, information she heard didn’t stick.

“It wasn’t making the connections upstairs,” Whaley said. “It took a lot just to get through a day, but as I went through therapy and nutritional supplements and changing my diet somewhat, incorporating more exercise, then things started improving.”

While her road to recovery was long and difficult, and it could not have happened with the help of many others, it was for her a real-life test to apply some of the principles laid out in her book, including a ganbaru mentality. Because of the effects of the TBI, completing the book was a personal triumph for Whaley that took some samurai spirit.

With today’s world experiencing a major disruption due to the current global pandemic, it might be worthwhile to use some wisdom from the past and use the title of Whaley’s book in these times — and let the samurai be your guide.

◊◊◊

Recent Books also Worth Exploring

‘An Eye for Injustice: Robert C. Sims and Minidoka’

Edited by Susan M. Stacy (ISBN13: 978-0-87422-376-7, Washington State University Press, 225 pages, © 2020, SRP $21.95)

Dr. Robert C. Sims, who died in 2015, had an esteemed career in academia, first as a high school history teacher, then in higher education with a three-decade stint teaching 20th century U.S. history and American ethnic studies at Boise State University, where he also served as dean of the College of Social Sciences and Public Affairs.

In 1968, while working on his doctorate in history at the University of Colorado, he attended a lecture by Roger Daniels, author of “Concentration Camps USA.” While he thought of himself as being pretty knowledgeable about American history, Sims was stunned — and later, outraged — to learn that up to that point, he, as a student and teacher of history, had never encountered anything in his formal studies about the government’s treatment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

In 1968, while working on his doctorate in history at the University of Colorado, he attended a lecture by Roger Daniels, author of “Concentration Camps USA.” While he thought of himself as being pretty knowledgeable about American history, Sims was stunned — and later, outraged — to learn that up to that point, he, as a student and teacher of history, had never encountered anything in his formal studies about the government’s treatment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

In the following decades, Sims made up for that initial lack of knowledge by researching, writing scholarly articles and interacting personally with Japanese Americans in Idaho and becoming one of, if not the, top authorities on Idaho’s Minidoka WRA Center.

Thanks to the efforts of Sims’ survivors and editor Susan M. Stacy, “An Eye for Injustice” compiles in one volume 40 years of Sims’ scholarly works and chronicles his efforts in the campaign to memorialize Minidoka as a National Historic Site.

‘Japanese American Millennials: Rethinking Generation, Community, and Diversity’

Edited by Michael Omi, Dana Y. Nakano and Jeffrey T. Yamashita (ISBN: 978-1-4399-1825-8, Temple University Press, 316 pages, © 2019, SRP $33.84)

The Issei are gone, the Nisei who still remain are becoming rarer with every passing day and their Sansei offspring are either receiving Social Security or nearly ready to.

The once-neat (well, it seemed that way on the surface) generational progression of Issei, Nisei, Sansei and beyond began fraying with the Sansei, as the upwardly mobile and educated beneficiaries of their elders’ sacrifices, coupled with advances in civil rights, meant that anyone could marry (or just shack up) and procreate (or not) with anyone, and could live wherever one could afford to.

The once-neat (well, it seemed that way on the surface) generational progression of Issei, Nisei, Sansei and beyond began fraying with the Sansei, as the upwardly mobile and educated beneficiaries of their elders’ sacrifices, coupled with advances in civil rights, meant that anyone could marry (or just shack up) and procreate (or not) with anyone, and could live wherever one could afford to.

Add to that a steady influx of Shin-Nikkei over the decades, and the increase in mixed-race and multiethnic Asians with partial Japanese heritage (looking at you, Sanseis), and the result is a diversity unlike ever before.

What was once abnormal is the new normal, and nowhere is that more evident than in the millennial cohort of the Japanese American community.

“Japanese American Millennials” is an academic examination of that change and evolution.

Among the many Asian American communities in 21st-century America, Japanese Americans are unique as being more established, more English-first and more acculturated and assimilated — yes, both loaded terms — than other groups dominated by newer immigrant stock.

While Japanese Americans are no longer the dominant Asian American group in numbers and influence, “Japanese American Millennials” probably points to the direction those other Asian American communities will also eventually, inevitably, take.