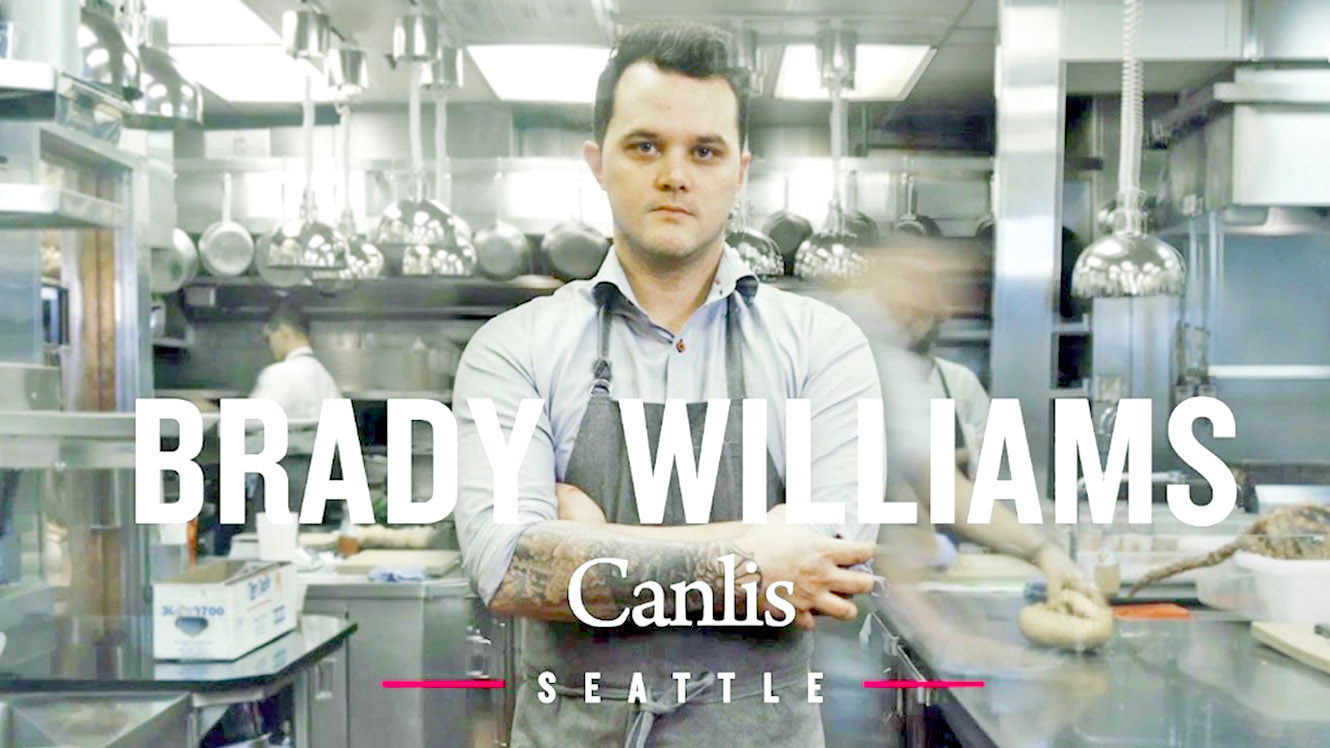

(Photo: YouTube)

Building upon the nostalgia of his grandmother’s cooking, James Beard-nominated rising chef Brady Williams embraces the old and the new as head chef at Canlis.

By Kristen Taketa, Contributor

Here is Brady Williams’ cooking philosophy in a nutshell: Put only a few high-quality ingredients on the plate, and “just try to not mess it up.”

Although Canlis, the award-winning Seattle restaurant that Williams leads, features American food — specifically of the Pacific Northwest persuasion — his way of thinking about food is ultimately Japanese. Williams’ way of cooking is to compose a dish using only what is necessary — to achieve a lot with a little.

“Japanese cuisine is achieving as much depth with as few ingredients as is possible,” Williams said. “You remove all the clutter, and only what is necessary remains.”

It’s a philosophy that Williams, who is partly ethnically Japanese, built off of the nostalgia of his grandmother’s Japanese cooking, especially eating katsu and pickled mackerel when he was young.

Two years ago, Williams scored the prestigious job as head chef of the Canlis restaurant in Seattle, likely because he embraced this disciplined way of cooking. The restaurant has a storied 66-year history and earned a prestigious James Beard Award for its wine program in early May. Williams himself was a finalist for the “Rising Star Chef of the Year” James Beard Award, which identifies chefs under 30 who are “likely to make a significant impact on the industry in years to come.”

The restaurant is often almost fully booked a month in advance. Its setting, which offers glass-window views of Seattle, Lake Union and the Cascade mountain range, is often attended for special occasions, has a sportcoat-level dress code and commands a $150, nine-course, chef’s choice tasting menu.

A seven-wine pairing is $145.

But all of that doesn’t make running a restaurant an easy job, Williams says.

Williams is one to admit that cooking is a profession that, while personally satisfying, has been glamorized by television. Even as a head chef, he gets to work by 11 in the morning each day and often doesn’t return home until 1 a.m.

“You have to love being a chef because it’s a lot of hard work. The hours are really long, and it’s very demanding on you as a person and in relationships and friendships and all sorts of stuff,” Williams said. “But if you love it, there’s nothing greater than serving people and being able to create a meal for someone.”

Not Salad, But Mackerel

Japanese food was a staple in Williams’ home growing up. His mother grew up in Yokohama, and his grandparents also came from Japan. For a time, when Williams was young, he lived at his grandmother’s house. It was “always a treat” when she cooked Japanese food for him, he said.

“It was funny because I was really picky growing up,” he said. “I wouldn’t eat salad, but I would eat pickled mackerel. I’ve been eating that as long as I could remember.”

Williams got his start working in restaurants when he was young. His grandparents had bought an American diner in Seal Beach, Calif., and his mother managed the restaurant while he worked as a bus boy and helped with meal prep.

He hated it.

“It wasn’t for me,” Williams reflected now. “I didn’t enjoy it at all. But sometime in college, I started working for myself, and food just became a more integral part of my life.”

Before attending Dallas Baptist University, Williams had moved out of his home to play junior professional ice hockey. He played for four years and moved around the country before settling in Texas for school, after an injury essentially ended his hockey career.

It was in college that he began viewing cooking as a desirable career alternative. He noticed that hockey and cooking had something in common: the amount of practice you put into each produces a logical, matching outcome of improvement.

“I call it measurable progression. You do something every day, you should be able to measure your progress,” he said.

But it was simple family backyard barbecues and other meals shared by his family that drew Williams into cooking and convinced him to pursue it as his new vocation. Even when there were hard times in his family, they still managed to congregate for a meal and appreciate each others’ company.

“I started thinking a little differently about food and the power of food to bring people together,” he said. “There’s a fellowship that would form around the table that wasn’t always there.”

Working From the Ground Up

Williams has never gone to cooking school. He could have attended, but he chose to defer enrollment before committing a lot of money to it. Instead, he educated himself by working as much as 19-hour workdays. He even worked without pay.

His first days as a cook were spent working an entry-level catering job from 5 a.m.-2 p.m., then a restaurant job from 3 p.m.-midnight each day. He spent whatever spare time he had reading whatever cookbooks were being released, such as “On Food and Cooking” by Harold Magee, “The French Laundry Cookbook

” by Thomas Keller and “Joy of Cooking

” by Irma Rombauer.

“All my free time was spent practicing cooking or reading about cooking or just immersing myself in cooking,” he said. “I was hungry.”

He ascended the ladder from working for free in entry-level jobs to working at higher-end restaurants, such as FT33 in Dallas, which focuses on hyperlocal cuisine. He left Dallas in 2012 for New York, working first at the pizza restaurant Roberta’s, then the two-Michelin star restaurant Blanca. Working at Blanca was the first time Williams worked with restaurant leadership that embraced a Japanese-like philosophy of cooking, the philosophy that would later drive his career to Canlis.

A Head Chef’s Job

About two years ago, he met folks who worked with Canlis through some mutual friends. They were looking for a new chef, but at first wrote off Williams, thinking he was too young. But about a month later, he got the invitation to a cooking audition for the head chef title at Canlis.

Unlike others vying for the job, Williams came to Seattle for the audition with nothing. He deliberately chose not to bring any prepared ingredients of his own, which many chef candidates typically do. Instead, he shopped around at local farmer’s markets to assemble his arsenal of ingredients. The strategy worked in his favor, and the eight-course meal he prepared was enough to convince the restaurant’s judges to name him chef.

A typical day for Williams looks like this:

The day begins around 10:30 a.m., when he arrives at the restaurant, gets himself organized and starts with restaurant prep. At noon, he meets with his five sous chefs to talk about the menu and the guests they will be serving later that day. Williams then typically spends time in meetings, either with the restaurant owners or local farmers with whom he works. At 2 p.m., his staff of about 20 cooks arrives to prep, and then Williams spends as much time as possible in the kitchen. There’s a daily meeting at 3:45 with the kitchen staff, then a 4 p.m. “family meal” when everybody shares a meal together. At 5, all staff gather for a final meeting before opening at 5:30. The last guests leave the restaurant around midnight, and Williams holds one more meeting at the end of the night to talk about the next day’s guests.

“We’re constantly trying to worry about tonight, but also we’re working on new dishes a month from now,” Williams said. “There’s a lot of creative development, just a lot of prep work to get through the day. Then there’s the whole managerial side, taking care of your people and making sure your staff feels cared for.”

Japanese-Inspired Food

Canlis’ food is best summed up as “Pacific Northwest cuisine with a Japanese influence,” according to Williams. The restaurant has a history of Japanese inspiration — its founder, Peter Canlis, had run a restaurant in Oahu, Hawaii, with a Japanese staff before starting his namesake restaurant in Seattle 66 years ago, according to Seattle Met. Similar to Japanese restaurants, there was an intended emphasis on service and hospitality.

Today, the restaurant seeks out high-quality ingredients, many of which come from cultivated relationships with local farmers and producers, and Williams and his staff uses them to create clearly Japanese-inspired dishes. For example, the restaurant makes its own miso from local chickpeas and hazelnuts, and gomashiyo,

similar to furikake,

from the spruce of pine trees. The restaurant’s current menu offerings includes a steak tartare made with Wagyu

beef, shima aji with a barley broth, asparagus poached in dashi

and a Japanese-style cheesecake with buckwheat and shiso.

“It’s really just trying to find things that are interesting to us and then using what’s around us to kind of marry the two ideas,” Williams said.

Like in Japanese cuisine, the restaurant keeps food light and free from excess. For example, the restaurant uses dashi instead of chicken for the basis of its stocks, and it refrains from using dairy.

“It’s not very busy, it’s not very over the top elaborate,” Williams said. “It’s really focused and hopefully fairly intense.”

Even most of the restaurant’s plateware is Japanese. Williams brings back ceramic plates from Japan himself. The restaurant also works with a Seattle-based potter from Hokkaido, Japan, to craft its own plates.

“It’s so ingrained, it is who I am, so it’s not like I’m appropriating something,” Williams said of the Japanese influences on his cooking and management. “It’s just how I think.”