Meeting at the White House on Aug. 10, 1984, to discuss redress. From left: JACL National Redress Committee Chair John Tateishi; Chief White House Domestic Affairs Adviser Jack Svahn; JACL National President Floyd Shimomura; Frank Sato, the highest-ranking Japanese American in the Reagan administration; and Lou Hayes, Svahn’s deputy. (Photo: Courtesy of Floyd Shimomura)

CWRIC hearings, a figure is reached and a secret White House meeting

By P.C. Staff

(Editor’s note: The following is Part 2 of an article that appeared in the Aug. 16-29, 2019, edition of the Pacific Citizen about the plenary from the 2019 National JACL Convention on the early years of redress. Read Part 1 here.)

Although disliked by many Japanese Americans both inside and outside the JACL at the time of its formation, the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians would prove to be one of the many critical building blocks to the eventual success of Japanese American redress via the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 that was enacted by President Ronald Reagan.

The CWRIC hearings allowed Issei and Nisei to not only publicly share the repressed-for-decades pain of their wartime experiences of removal and incarceration at the hands of the federal government and thereby educate lawmakers and the general populace, but also the commission’s findings and recommendations served to underpin everything that was yet to come.

Nevertheless, those hearings were painful for everyone involved.

“That was the most-grueling, difficult experience I had ever gone through in my life, sitting there in these hearings,” said John Tateishi, chair of the JACL’s National Committee for Redress. “I felt guilty because I was involved in the decision and trying to get this to happen. I felt it was my obligation to sit through the hearings, but I could only take so much at a time. After a couple of hours, I’d have to go outside and get relief.”

Following the meeting with the “Big Four” — Sens. Inouye and Matsunaga, and Reps. Matsui and Mineta — (see Part 1 of this story, P.C. Aug. 16-29, 2019), the JACL’s National Committee for Redress met in March 1979. Tateishi said that “nobody liked the idea of a commission.” But in a vote of 4-2, a decision was made to pursue legislation to create what would become the CWRIC.

Tateishi knew the reaction to the committee’s vote would bad.

“But I had no idea how bad it would be,” he said. “It was one of those things where you feel like finding somewhere to go hide. The reaction within the JACL was just as harsh as it was in the community.”

It would take some political sleight-of-hand to show that the majority of JACL members were on board with the idea of a commission.

“Karl Nobuyuki, who was the director at the time, he and I decided we should do a ratification process and silence our critics. It was risky, but we did an assessment and thought we could get the chapters to support this,” Tateishi said. “We did the mailing, and we got back results, and we announced it vaguely that there was a 5-1 decision to support the commission strategy.

“What we didn’t say was that the majority of the chapters didn’t vote,” Tateishi continued. “They were so upset — this was the way they voiced their protest. If they had voted, that ratification would have been against the idea of the commission strategy.”

◊◊◊

In hindsight, the value of the CWRIC seems obvious. But just how harsh were the reactions to the concepts of a commission and redress itself?

“They were opposed to redress because they didn’t want to talk about camp,” Tateishi said, referring to the Nisei. “What happened to us is that after the war, we built that wall of silence. Nobody talked. A lot of the Niseis didn’t tell their kids about what they experienced.”

Getting the Nisei to talk at the CWRIC hearings was crucial, Tateishi said because “without the Nisei, it would have been an utter failure.”

“My biggest fear was, ‘What in the hell do we do when the commission comes to town?’ The whole purpose was to get Japanese Americans up there, speaking about what they experienced. I didn’t know if it would work because as Ron (Wakabayashi) pointed out, in these mock hearings we held, no one could get through their testimony.”

Ultimately, as history shows, the gamble paid off.

[quote style=”boxed”]“Something really remarkable took place, and it was a cumulative effect of a lot of people’s contributions. We did it drop by drop.”• Ron Wakabayashi, former JACL national director[/quote] After the schedule for the 10 hearings in several major U.S. cities — including Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, San Francisco, Seattle and Washington, D.C. — was released in 1981, survivors of the camp experience did come out and talk.

“It was a really courageous thing they did, and it was difficult for them,” Tateishi said. “They’re the ones who changed the mind of the country about what happened to us because every night it would be on the news, every hearing we had.”

Moderator Floyd Shimomura added, “I think that the response that the Nisei got was a great deal of sympathy and sorrow for the hardship that they had to go through, from friends and people who knew them, and I think that started to make them think they could come out and talk about this.”

◊◊◊

During the era of redress that this plenary covered (1977-84), it was noted that things we now take for granted, such as inexpensive long-distance phone calling, not to mention e-mail and social media, did not exist. Therefore, disseminating news of the redress campaign via the mass media — meaning mainstream newspapers and the three national TV networks — took cleverness and making the most of the opportunities as they presented themselves.

As noted, Sen. S. I. Hayakawa (R-Calif.), who was the keynote speaker at the Sayonara Banquet at the 1978 JACL National Convention, denounced the idea of pursuing monetary compensation.

The day before, the JACL had approved the resolution to pursue redress, including a demand for $25,000 per person in compensation.

Tateishi got laughs from the audience when he said, “To this day, I have no idea how Hayakawa was invited to keynote at the Sayonara Banquet.”

Still, it was no laughing matter at the time because there were newspaper reporters in attendance who would report Hayakawa’s opposition to monetary redress, which Tateishi remembered Hayakawa describing as “absurd and ridiculous.”

It was necessary to turn Hayakawa’s lemons into lemonade.

Tateishi quickly drafted a news release to counter Hayakawa’s position, which he gave to the reporters. Both he and JACL National President Clifford Uyeda also spoke “very briefly” with the reporters.

“They incorporated part of our press release in the story, which to me was important because I knew that story would go on the wires, and it did. In the matter of a week, the Wall Street Journal came out with an editorial titled ‘Guilt Mongering,’ and it quoted Hayakawa, and it was an anti-redress editorial. That was what got us into the national level of debate on this issue, which was precisely what we were trying to do, to make this a national debate,” Tateishi said. “That was Hayakawa who did that for us.”

Asked by Shimomura whether Hayakawa’s statements helped or hurt the cause, Tateishi said Hayakawa’s opposition ultimately was a boon for redress because after the Wall Street Journal’s editorial “ … we flooded them with letters to the editor.

“Then the New York Times came out with an editorial, completely different,” Tateishi continued. “We had it all set up so that we had people in different parts of the country ready to send in letters, and we concentrated the letters from people who were locally from an area. That was pretty much the media campaign.”

At the end of the day, even though Hayakawa’s stance was “disastrous,” Tateishi said they saw a way to work it to the advantage of redress.

◊◊◊

In another media-related anecdote, Ronald Ikejiri, JACL’s Washington representative from 1978-84, recalled how he and Rep. Dan Lungren (R-Calif.), who served as the vice chair of the CWRIC and was its lone member who was against monetary payments, both appeared on Larry King’s overnight radio show.

“It was a cordial discussion, but it was very obvious Larry King was all for redress,” Ikejiri said. “Every time that Dan Lungren would come out with ‘no money,’ they deserve an apology, [King] would turn it around. He would help my argument, our argument, go in a different direction.”

Another tactic that kept the mainstream news media informed of the progress of the redress campaign was baked-in from the beginning, according to Tateishi, at the January 1979 meeting between the JACL National Redress Committee and the Big Four.

Tateishi credited Inouye for insisting that educating Americans be one of the objectives of the redress campaign, especially with regard to preventing such an occurrence from happening again. But he also had a practical idea from a publicity perspective.

“He said one of the things you could do is have the commission issue its report and then wait six months and have them issue the recommendations,” Tateishi said. Splitting those items would keep the issue in the news over a longer period of time, thus keeping it from being forgotten or buried.

As it turned out, it was less than six months, Tateishi noted, adding that when the CWRIC report was issued, it led the news on ABC, CBS and NBC. About three months later when the CWRIC held another press conference and released its recommendations, the same thing happened.

“Every network and most local news started with the recommendations of the commission, which was $20,000, an apology and a trust fund,” Tateishi said. He also revealed why the original amount of $25,000 in monetary compensation became $20,000.

Tateishi noted how he had met on several occasions with Joan Bernstein, chair of the CWRIC.

“I was arguing for the commission to come out with monetary compensation, which was the JACL’s position. And then we started talking about the amounts,” he said.

Tateishi told Bernstein that he had heard the commission was considering compensation of $10,000.

“If you come out with an amount that low, the JACL is going to be screaming. It’s an insult,” he said.

Another figure being tossed around was $15,000. She told Tateishi it was likely that the commission would go with $20,000.

“I said, ‘It’s not enough.’ Why not come out with $25,000?” he said.

Bernstein’s answer: “John, you know if we come out with $25,000, it’s going to look like we’re under the thumb of the JACL.”

“That’s why they came out with $20,000,” Tateishi said.

Interjecting from the audience, former Congressman and Cabinet member Norman Mineta chimed in and noted that it was the CWRIC’s special consul, Angus Macbeth, who finally said, “Tie it down,” meaning stop deliberating and just decide on a monetary figure.

In other words, eligible Japanese Americans received 80 percent of what the JACL originally asked for — and the CWRIC didn’t look like it was being a puppet of the JACL.

◊◊◊

When panelist Frank Sato was introduced, Shimomura noted that he had served JACL at the national level, first as secretary-treasurer, then as national president.

Sato was the “highest-ranking Japanese American in Ronald Reagan’s administration. He served as inspector general for the Department of Veterans Affairs. His appointment required Senate confirmation,” Shimomura said.

Shimomura noted that under President Reagan, Sato was “selected as the chief auditor for a committee that was trying to reduce wasteful spending, and he was highly regarded by Reagan and his administration. That’s indicated by the fact that in 1985, Reagan gave Sato the award for meritorious service and also another award in 1987 for distinguished executive service. That was the very same period when he was serving as national president of JACL. The Reagan administration approved him taking on this responsibility at that time.”

Sato, who was already a JACL member, said he became involved in JACL at the national level at the urging of Ikejiri, who was already a member of Sato’s “kitchen cabinet.”

Ikejiri noted how the JACL national president before Floyd Shimomura, (James Tsujimura), had asked Ikejiri to write a letter to the White House to request a meeting.

“I got a letter back, and they said, ‘I’m sorry, the president is very busy, and we can’t meet with you,’” Ikejiri said.

A meeting at the White House to discuss redress, however, just might boost its chances.

◊◊◊

According to Sato, “Ron says to me one day, ‘Frank, why don’t you run for (JACL) national president?’ and I said, ‘Ron, you’re out of your gourd,’” which got laughs from the audience.

Nevertheless, Sato credited Ikejiri’s persistence since he knew Sato could someday be of help to JACL.

“When anybody says, ‘We need your help’ to me, you get my attention. He says, ‘You’re a financial guy. You run for secretary-treasurer of JACL, and after you get that done, and if you’re comfortable, run for JACL president. And that’s exactly what happened.”

“When I ran for secretary-treasurer, I won by 114 with one abstention,” Sato recalled. “Two years later, I ran for national president against our icon, Min Yasui. I won by one vote.

Sato noted that as part of his duties under the Reagan administration, he was already meeting regularly with people at the White House, and among them was Jack Svahn, who was the assistant to the president for domestic policy and the chairman of the president’s council, of which Sato was also a member.

After being rejected once, Ikejiri wanted to try again to get a meeting at the White House.

Photo from a “secret meeting” at the White House from August 1984. PIctured (from left) are Floyd Shimomura, John Tateishi, Frank Sato and Lou Hayes. (Photo: Courtesy of Floyd Shimomura)

“So then I went and talked to Frank Sato, and I said, ‘Frank, you have contacts and long-term relationships with the Reagan administration. Is there a way we could set up a meeting?” Ikejiri recalled.

“When the time came that Ron wanted me to call a White House meeting, I got it done for him,” said Sato, who said that for him, “Getting a meeting was easy.”

There was one catch: No one could know about the meeting.

Photo taken outside of the West Wing of the White House in August 1984. Pictured (from left) are Frank Sato, Floyd Shimomura and Ronald Ikejiri. (Photo: Courtesy of Floyd Shimomura)

“I told Floyd, John and Ron, you gotta keep this thing quiet,” Sato said. “In D.C., if people want to get you for anything, they’re going to dream up stories, pitch dirt at you, and the next thing you know, perception becomes reality, and I’d be gone.

“But worse, the danger that I was afraid of was I didn’t want anything to endanger the redress program,” he continued. “So, I asked the staff not to talk about our meeting in the White House.”

There could be no potential for someone to claim Sato had a conflict of interest.

Sato called Svahn’s office and got connected right away.

“I said, ‘Jack, I need to get a meeting set up with Floyd Shimomura, national president of JACL, and here’s what we’re working on.’ I briefly explained to him the redress issue, and he said, ‘Why, of course,’ and we had a meeting set up for the next week.”

Sato said he was “kind of surprised” it happened so quickly. “Thankfully, guys like Ron Wakabayashi and the staff had put together a book — and I still remember the book — it was a black three-ring binder with a bunch of stuff in it.

“But there was one key item in there, and it was an article about President Reagan, who was then Capt. Reagan, who had accompanied Gen. (Joseph) Stilwell to this service for Staff Sgt. (Kazuo) Masuda.”

Sato was referring to an incident in 1945 at which Stilwell, accompanied by Reagan, presented the Distinguished Service Cross medal posthumously awarded to Masuda, to his sister, Mary.

Reagan famously said, “Blood that has soaked into the sands of a beach is all of one color. America stands unique in the world, the only country not founded on race, but on a way — an ideal. Not in spite of, but because of our polyglot background, we have had all the strength in the world. That is the American way.”

“I didn’t know it until later on, but I found out that Carole Hayashino is the one who dug up that info that we took into the White House,” Sato said. (Hayashino had been scheduled to be on the same panel but had to bow out due to a family emergency.)

Sato said after he, Ikejiri, Tateishi and Shimomura had this White House meeting with Svahn and his deputy, Lou Hayes, he never received any feedback of what transpired subsequently — and with the self-imposed secrecy he requested, the meeting might as well have never happened.

“The only thing I knew is Jack would always say to me at subsequent meetings, ‘Don’t worry about it, Frank. We’ll take care of it,’” Sato said.

◊◊◊

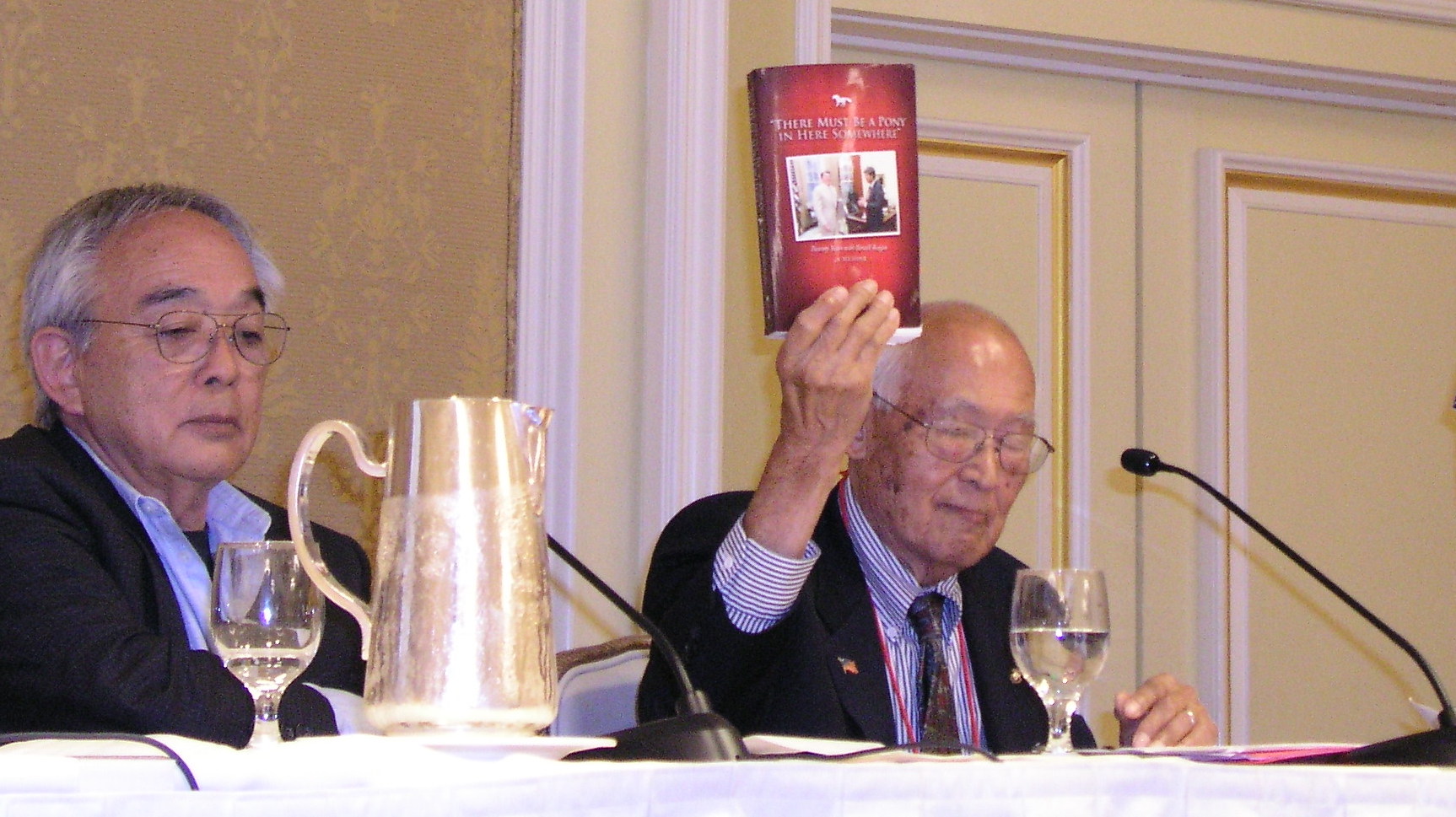

Former JACL President Frank Sato holds up a copy of “There Must Be a Pony in Here Somewhere,” a memoir by Jack Svahn, who served during the Reagan administration as the assistant to the president for domestic policy and the chairman of the president’s council. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Sato then related how a few months ago he received a call from Shimomura to share something that he had learned, namely that Svahn had written a memoir published in 2011 about his 20 years of working with Reagan, titled “There Must Be a Pony in Here Somewhere.”

Sato received a copy from Shimomura, and when he had the chance to read it, he finally learned about the impact of that meeting.

“I started glancing through this thing, and sure enough, there are some references to redress,” Sato said. “It’s talking about the Masuda story and the famous quote, ‘blood in the sand,’ that you’re all familiar with. And he talked about the fact that he had mentioned to the president that before the next Veterans Day, maybe the president could support this bill.”

Shimomura later said he was glad Svahn wrote his book because once he had written about what had occurred, they, too, could finally break their silence.

In the book, Sato learned that Svahn had “taken this whole subject and made it an issues item on a Tuesday presidential meeting in the Cabinet room.”

“So we did have some effect from that, that we didn’t fully understand or appreciate… . I don’t think the organization — JACL — fully appreciates what all these guys have really done as Sanseis that the Niseis just weren’t ready to step up to the table to do,” Sato said. “I’d like to ask all of you to join me in applauding all of these guys.”

◊◊◊

As for Shimomura’s thoughts on redress, he noted how unintended consequences are usually thought of as being bad.

“But here, I think, a lot of the unintended consequences were actually good. It was almost kind of magical in a way,” he said.

Shimomura also noted that with the subject of reparations for African-American descendants of slaves again a topic of discussion, people are looking to the Japanese American redress campaign as a model.

For his part, Ikejiri’s view was that “when you talk about redress, redress really is about people and interrelationships. It was just one of those wonderful things.”

He also announced that the panelists had taken up a collection to buy Mineta a rocking chair like the one that President John F. Kennedy made famous. “It’s not for you to rest in. It’s for you to work in,” he said.

Regarding redress and its meaning in the intervening years, former JACL National Director Ron Wakabayashi said, “Something really remarkable took place, and it was a cumulative effect of a lot of people’s contributions. We did it drop by drop.”

He closed by asking the audience to give a “shaka” salute to Hayashino, which he recorded on his smartphone to share with her.

President Reagan enacts H.R. 442 on Aug. 10, 1988, four years to the day after a secret meeting at the White House between JACL members and Reagan’s Domestic Affairs Adviser Jack Svahn.