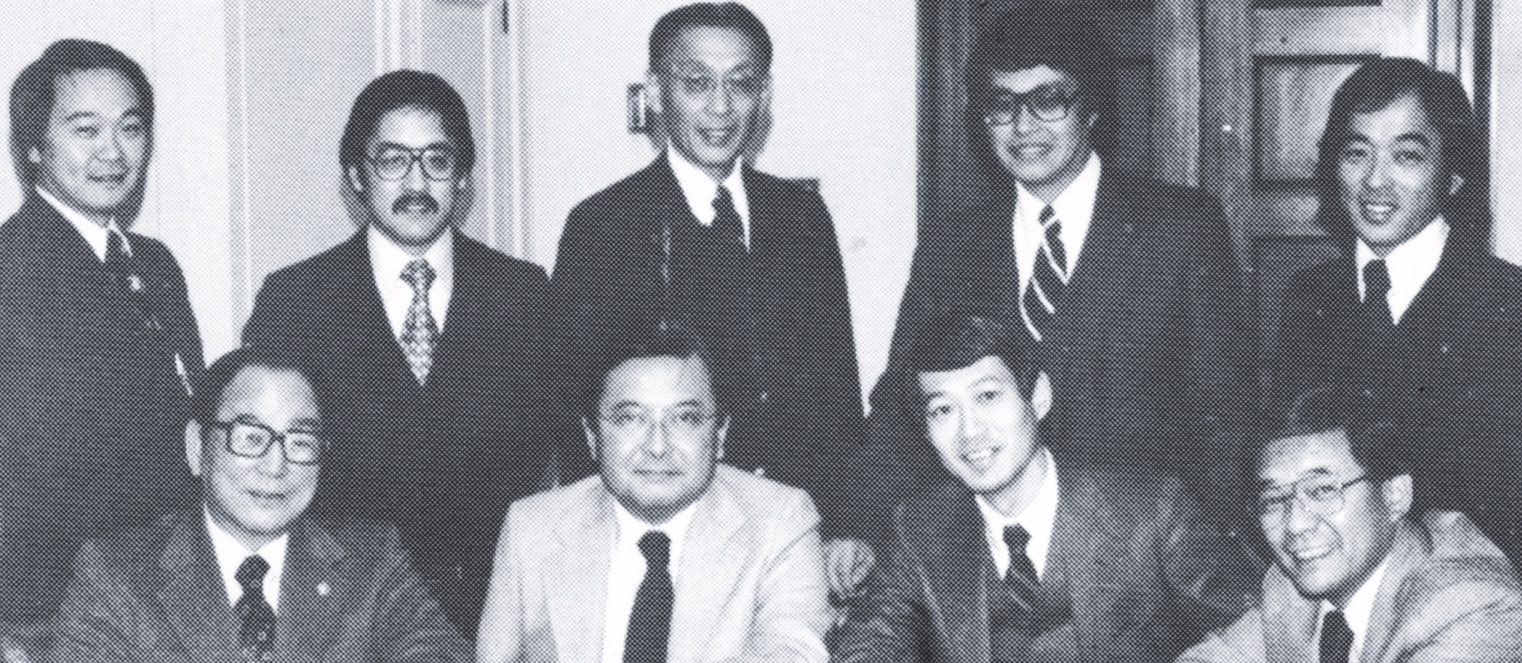

In this Pacific Citizen file photo, JACL representatives meet in 1978 with the “Big Four” Japanese Americans in Congress, a meeting described in John Tateishi’s new book “Redress: The Inside Story of the Successful Campaign for Japanese American Reparations.” Standing, from left: Karl Nobuyuki, Ron Mamiya, Clifford Uyeda, Ron Ikejiri and John Tateishi. Seated, from left: Sen. Spark Matsunaga, Sen. Daniel Inouye, Rep. Robert Matsui and Rep. Norman Mineta.

John Tateishi offers his take on the civil liberties win for Japanese Americans in his new book ‘Redress: The Inside Story of the Successful Campaign for Japanese American Reparations.’

By P.C. Staff

The late Daniel K. Inouye is known for many things: serving during World War II in the Army’s 100th Battalion/442nd Regimental Combat Team (where he lost his right arm), being awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, which was later upgraded to the Medal of Honor and, of course, for his decades as a U.S. senator representing Hawaii.

Regarding the years-long, ultimately successful drive to obtain redress for Americans of Japanese ancestry whose rights were abrogated during WWII, Inouye is credited for suggesting a then-controversial and unpopular tactic that would later prove essential: the formation of a congressional commission to investigate the circumstances that led to the forced removal from the U.S. West Coast and subsequent incarceration of ethnic Japanese.

In the new book “Redress: The Inside Story of the Successful Campaign for Japanese American Reparations” (Heyday, ISBN-13: 978-1597144988, 400 pages, SRP $28), author John Tateishi told the Pacific Citizen that the reason he took the time and put in the effort to complete the book was because of Inouye, “who bugged the hell out of me for years to record the history.

In the new book “Redress: The Inside Story of the Successful Campaign for Japanese American Reparations” (Heyday, ISBN-13: 978-1597144988, 400 pages, SRP $28), author John Tateishi told the Pacific Citizen that the reason he took the time and put in the effort to complete the book was because of Inouye, “who bugged the hell out of me for years to record the history.

“He once told me, ‘You’re the only one who knows how this all evolved and how it went from something impossible to fruition, as a rare success in United States history,’” Tateishi recalled. “He said, ‘It’s really important that somebody record that history of the campaign because otherwise it’s going to get lost.’”

Like the concept of what would become the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians — an idea and course of action Tateishi said he initially “hated” and was, within the JACL, “so controversial and so highly criticized” — Inouye’s advice to document the path to redress in the form of a book was one that Tateishi eventually got behind. But, like redress itself, it wasn’t easy, and it took years to complete. [Editor’s note: See related article here.]

Tateishi said he originally intended to write “more than anything, a record of the redress campaign from my perspective of having been involved in it very early on and understanding the history of how the whole concept of redress evolved in the community.”

As someone who as a boy experienced life in a concentration camp for Japanese Americans and later as the JACL’s national redress chair and national redress director, followed by a stint as the organization’s national executive director, Tateishi did indeed have a unique role in and perspective on the winding path it took to have redress go from “a fool’s errand” that was “doomed to failure” (and those assessments were from friends) to one of the rare instances in U.S. history in which an aggrieved group won token monetary compensation — $20,000 in 1988 — and an apology from a U.S. president.

While Inouye’s insistence did eventually cause Tateishi to commit his recollections to the page, he said, “I resisted him for, 10-15 years. Almost every time I’d run into him, he would say, ‘Hey, you need to write that record.’ It got to the point where, quite honestly, I would see him and avoid him because I knew he would bug me.

“Finally, one day I decided I would record the history, which I did,” Tateishi continued. “I started writing with the intent that I would do something fairly succinct. But as I started writing it, I realized there was a lot to the redress campaign that you can’t just record as sequential events, the chronology of what happened from Point A to Point Z because there were all these side roads that you had to travel through to understand why we did what we did.

“The more I wrote, the more I realized there was much more to write,” Tateishi said.

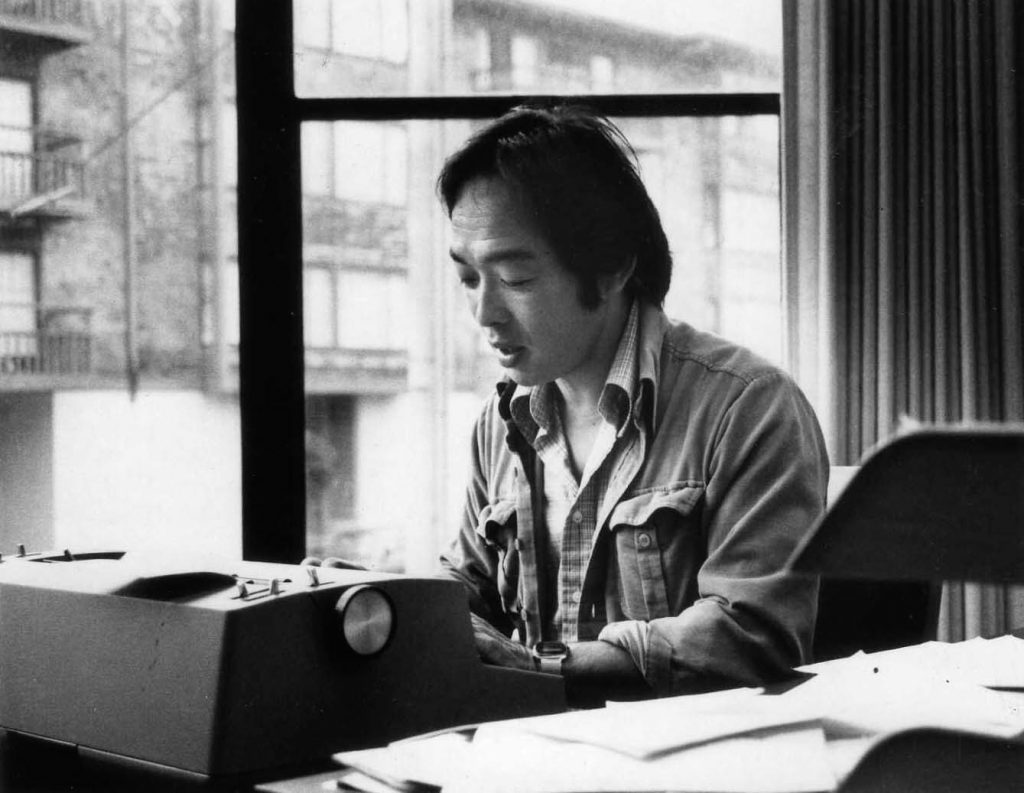

John Tateishi, seen in this file photo, recalls his experience as an early JACL leader in its redress campaign in his book “Redress: The Inside Story of the Successful Campaign for Japanese American Reparations.” (Photo courtesy of John Tateishi)

The result was a 600-page manuscript, which Tateishi began writing in 2007. That might be fine as a private document, but to publish that story to share with the public would require a different tack.

Tateishi had to then take time rewriting it, and the result was a 400-page tome that gave his perspective on his years in the redress movement.

Inouye, of course, is a prominent part of Tateishi’s book. But so, too, are names familiar to longtime JACLers: Sen. Spark Matsunaga and Rep. Robert Matsui, as well as JACL staffers and prominent members such as Mike Masaoka, Minoru Yasui, Bill Marutani, Clifford Uyeda, Bill Yoshino, Ron Ikejiri, Frank Sato and Ron Wakabayashi.

But as far as politics were concerned, the other Japanese American bigwig besides Inouye was Rep. Norman Mineta.

According to Tateishi, while JACL was ahead of curve in the Japanese American community regarding redress, Mineta was ahead of the JACL. Recalling his first encounter with Mineta, Tateishi said it occurred when he was involved with the Northern California-Western Nevada Pacific District as a committee chair and was visiting JACL’s headquarters to get some information.

“Norm walked in, and my reaction was, ‘Oh my gosh, there’s Norman Mineta!’ We said hello, but there wasn’t any kind of exchange that was significant,” Tateishi remembered.

Tateishi overheard, however, a conversation between Mineta and a couple of JACLers also present, and the topic was redress.

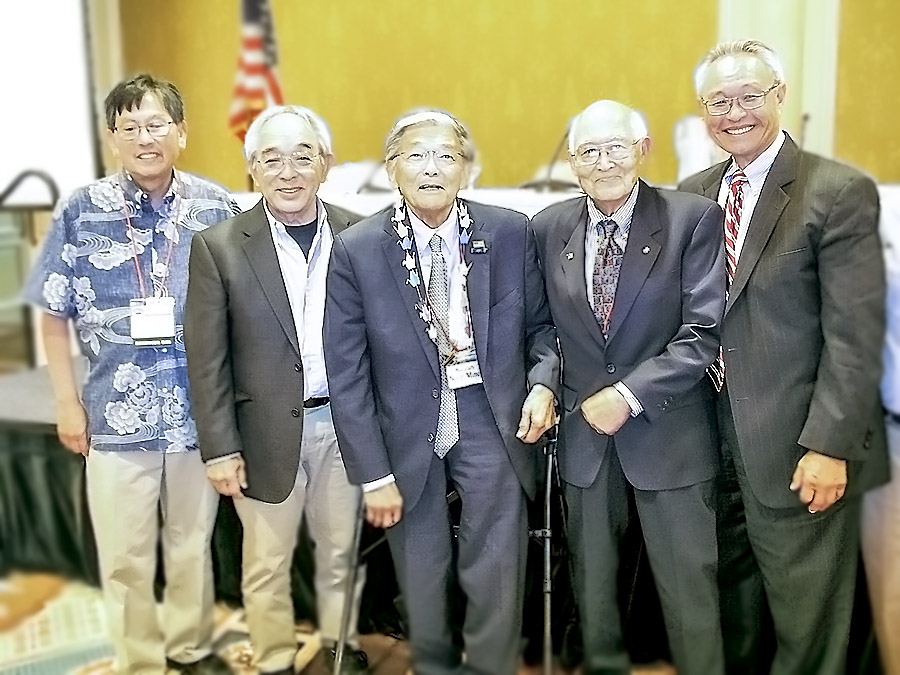

Floyd Shimomura, John Tateishi, Norman Mineta, Frank Sato and Ron Ikejiri participated in the 2019 plenary titled “Early Redress Years: Reparations,” which took place at the 2019 National JACL Convention in Salt Lake City. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

“My takeaway from that as I left the building and was headed home was, ‘Mineta is really insistent on this. He is driving the JACL into this issue,’” Tateishi recalled. “He was ahead of the JACL on his thinking.

“Early on, we depended on, basically, two people in D.C.: Dan Inouye and Norm Mineta,” Tateishi said. “If you don’t have Dan Inouye and Norm Mineta, you ain’t going to get anywhere.”

Tateishi said he thinks he was 38 when he became JACL’s national quarterback on redress.

“And in the eyes of the Nisei, I was still a kid. You don’t get legitimacy with the Nisei until you turn 50, maybe,” he said. “I was just arrogant enough to think I knew how to do this, that I could figure this one out — and that I already had.”

Tateishi saw two paths: through the courts or legislatively, meaning via Congress. The latter would prove to be the longer, more convoluted and more difficult choice. “It would require more of a grassroots operation to make it work,” he said.

But thanks to Inouye’s insistence to form the CWRIC — overriding both Mineta and Matsunaga — not only did the public become educated on the issue, but also Congress itself realized that a wrong had been committed.

“The United States Congress actually recognized it (the internment) as an injustice. It was phenomenal and that came when they accepted the commission report,” Tateishi said.

“When I first got involved in the JACL, the discussion of reparations was something that not everyone understood,” Tateishi said. “It was thought that, ‘OK, you file a complaint with some governmental body, they mull it over, and they decide to give you money.’ That was the basic concept people had about reparations, and I knew it was much more complex than that.”

In 2020, with the idea of African American reparations for slavery bubbling under the zeitgeist as a mainstream topic — or at least a question thrown at presidential candidates — are there lessons to be learned from the Japanese American redress campaign and is the topic of African-American reparations viable?

Comparing African-American reparations to Japanese Americans reparations, Tateishi noted that historically, the paradigm for race relations has been black-white — but the Japanese American redress campaign didn’t fit that dynamic.

“There are significant differences,” Tateishi said. “I don’t know what their chances are. I think they have a very tough battle, especially with the kind of politics that exist in America today. I think as long as you have a bunch of bigots and racists and white supremacists running the country, appealing to that same characteristic in a segment of the population that believes that it’s OK to use racial epithets, to treat people as less than equal and in some cases, less than human. I think the chances of achieving reparations for African-Americans is so slim, if I were in that battle, I would find it pretty depressing right now.”

Tateishi added, “The one advantage they have, I think, is that reparations is no longer without precedent. We set the precedent for something that never happened in this country before. All groups that were treated unjustly and will be treated unjustly at some point have as a precedent Japanese American reparations, and that’s something that never existed before we took on this issue.”

John Tateishi began writing his new book, “Redress,” in 2007. The book was just released this month. (Photo: Chloe Coleman)

An undertaking as big as redress meant dozens of people with differing personalities, temperaments and ideas would have to work in concert — or not. Asked how he resisted the urge to use the book as a way to settle scores with certain individuals, some now deceased, Tateishi went back to one of his conversations with Inouye, when he was still trying to get Tateishi to write a book.

“I can do this, but only if I were completely honest, which meant I would have to show all the dark sides of the campaign and all of the ugliness that went on,” Tateishi said he told Inouye. “I had a difficult time with a lot of people in the campaign, a lot of people in the community. I wasn’t well-regarded in the community because of some of decisions I had led my committee to make and the directions we had taken. One day, Mike Masaoka said to me, ‘So now you know how it feels,’ half-jokingly. But I could see the pain in his eyes.”

As for his relationship with Minoru Yasui, there is genuine regret over how his once-close relationship with him deteriorated.

“There’s a certain kind of tragedy, almost like a Greek tragedy, to Min,” Tateishi said. “He aspired for so much and hoped so much could be done and never saw it come to fruition.” Yasui died in 1986.

Tateishi noted how Yasui — an attorney — tutored him through a lot of the early stages of the thinking about reparations, the legal side of what they were attempting.

“We developed a really close relationship,” Tateishi said. “It turned sour towards the end as the battle between the two sides of the JACL, basically for control, started getting really personal. There was a falling out.”

It was a reference to the rise of the Legislative Education Committee or LEC, which would turn JACL, in Tateishi’s eyes, into a one-issue organization focused solely on redress.

“We would still talk, and he would sometimes give me a call and say, ‘Look, here’s what’s happening.

I just don’t want you to get blindsided by this and would tell me what some of the thinking was,” Tateishi said. “It was like trying to make sure the other person was OK. Min to me is really an important figure in the campaign, and I was really sorry to see that we ended up in different camps on how things would evolve.

“It bothered me, but that’s the way things go when you get involved in the politics of organizations.”

Still, Tateishi gave credit to that “different camp” for its role with regard to the success of redress. “The LEC (Legislative Education Committee) fought a really hard battle in the last year and a half of the campaign. They pushed it over the top. They got Congress to support the legislation, and then there was Ronald Reagan in the White House, and I talk about that in the book.”

By that time, though, as redress had entered its home stretch toward becoming a reality with President Reagan’s signature in August 1988, Tateishi was no longer an active participant in the campaign — and his book reflects that.

“What you’re seeing in this book is through my eyes and my experience. So, there’s a lot of focus on the part that I experienced personally, and for that reason, I don’t go into a lot of details about the last year and a half/two years of the campaign, where it was an LEC-led effort. I know some of what went on, but I’m not going to presume that I understood what they were doing and all the things.

“I think that if the LEC feels offended that there’s not more about what they did, they need to write that book,” said Tateishi.

With the publication of “Redress,” Tateishi added, “There will be, among some of the LEC folks, a kind of reaction to say this isn’t the story, this isn’t what redress was. They would want to tell the story from that perspective. Part of what Dan Inouye kept saying to me was, there are people who think everything that came before wasn’t very important, that we just put this commission together, had the hearings and everything led to, finally, the fight in Congress for the reparations bill.

“But the huge battles that took place in the community are something that get ignored and the descriptions that I’ve seen about what it took for us to succeed with what we did,” Tateishi said. “I get asked the question sometimes, if we didn’t ultimately end up with the checks, would this have been a failure? Yeah, in a way it would, but in a way we accomplished something much greater than that. To me, the campaign was always about something much greater than us. It wasn’t about us getting $20,000 so much as it was about making America secure in the future, so that what happened to us will never happen again to any other group.”

Excerpt from ‘Redress: The Inside Story of the Successful Campaign for Japanese American Reparations’

[Editor’s note: The following is an excerpt, reprinted with permission, from “Redress.” In this selection, Tateishi recounts his recollections of John McCloy during the hearing of the CWRIC. McCloy, who served as President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s assistant secretary of war, was, with Karl Bendetsen, one of the “… principal figures responsible for the government’s wartime policies against Japanese Americans.”]

And then there was John McCloy. He was a perfect study in contrasts with Bendetsen. Where the latter was very contained and restrained, quietly combative in the way an executive might be, McCloy was an amiable sort, openly friendly to the commissioners with whom he was acquainted, a man full of energy and political poise. He was very sure of himself, even in the face of the hostile grilling he knew awaited him. Even as he walked to the witness table and addressed the commissioners, he exuded the kind of confidence that comes from years of public service at the top levels of government and from having spent much of his political life dealing with world leaders, including the most obstinate and dangerous among them. There wasn’t a fine line between his arrogance and confidence — they were one and the same.

There was nothing excessive or flamboyant about McCloy. Dressed in an expensive suit and armed with a sharp mind and wit, he could cross verbal swords with the quickest of the commissioners. He knew about government commissions — I suspect he had created more than his share — and knew he would face tough questions from this body of mostly Democrats. McCloy was an East Coast Republican who in 1940 had taken a top-level position in the Democratic Roosevelt administration, which was made up of other East Coast intellectuals who had built their reputations in the White House by bringing the country, and the world, out of the Great Depression through sheer force of intellectual will and political courage. McCloy had presence, the kind that drew eyes to him in a crowded room, and especially in an environment he knew so well, such as a federal commission hearing. This was clearly a man who understood power from the position of someone used to wielding a great deal of it.

McCloy’s presence dominated the room, and it was interesting to see how Joan Bernstein paid deference to him as they parlayed back and forth in an exchange about which of McCloy’s many official titles they would use to refer to him during the hearing. She was an attorney who herself had spent many years working at high levels of government, and so she shared McCloy’s system of determining who is, and who isn’t, important on the Washington scene. He definitely fell into the former category, and they both knew it. That said, her deference was politic: she showed respect but not one ounce of intimidation.

McCloy began his testimony by describing his position and responsibilities within the Roosevelt administration at the outbreak of the war and his role overseeing the exclusion and detention policies under EO 9066. He detailed how and why decisions were made, and recounted the difficulties the FDR inner circle had struggled with as it dealt with the question of what to do about the Japanese American population in the face of the often harsh and unyielding demands of the political voices on the West Coast. At no time did he seem to feel the need to justify or rationalize the decisions or apologize for anything he may have done or caused to happen in relation to the exclusion and imprisonment of Japanese Americans.

I was fascinated by McCloy. Here he was, an eighty-one-year-old man, his mind like a laser, recalling minute details in reports he had read or conversations he had had forty years earlier. His memory was so vast and so defined that the commissioners who tried to challenge him found it difficult to do so.

Unlike Bendetsen, he did not become defiant and defensive or try to evade questions about his responsibilities as assistant secretary of war, and he did not attempt to shift the blame to others by stating that he was only following orders. McCloy was combative and never contrite: he was sure of himself and did not shirk responsibility for the role he had played in the internment. Although it was FDR who made the final decisions and Henry Stimson to whom McCloy was accountable, it was he who was responsible for formulating the policy that changed our lives forever.