Nakashima’s signature model: a conoid table and chairs. (Photo: Rob Buscher)

JACL Philadelphia chapter members visit the iconic Nakashima Woodworkers Studio, where some of America’s greatest wooden furniture pieces have been designed and made

By Rob Buscher, Contributor

On the sleepy outskirts of New Hope, Penn., some 40 miles northeast of Philadelphia, lies the Nakashima Woodworkers Studio. Tucked away on a wooded rural road between farms and secluded residences is a complex of buildings that blend modernist architectural techniques with traditional Japanese aesthetics and home to where the Nakashima family has lived and worked since 1945.

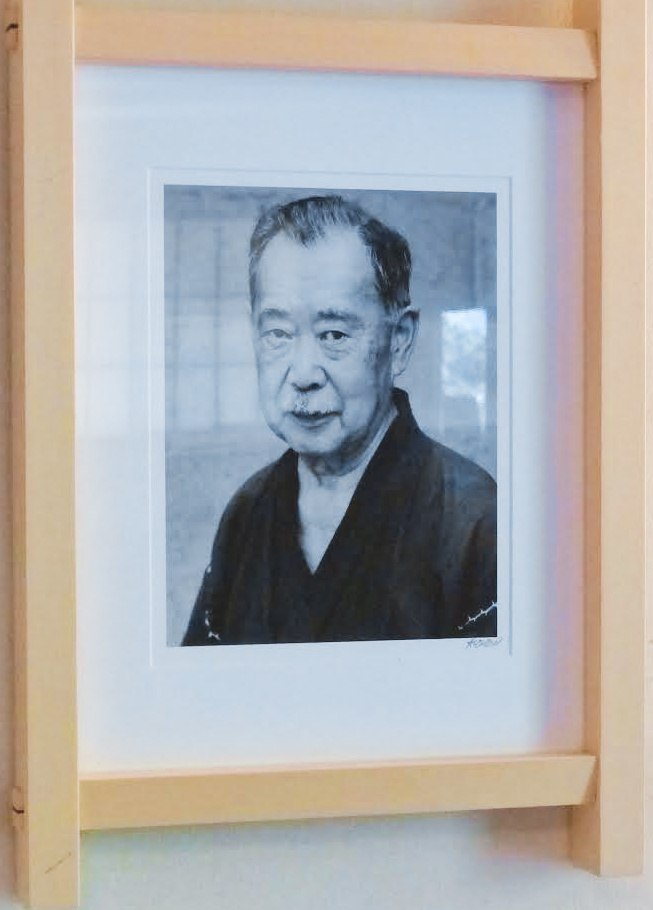

A photo of founder George Nakashima hangs inside the studio. (Photo: Rob Buscher)

The studio’s founder, George Nakashima, is perhaps the most significant American woodworker and furniture designer of Japanese descent, who lived and worked in Pennsylvania for nearly 50 years. JACL Philadelphia chapter members enjoyed a trip to the late artist’s studio in June.

Amongst furniture collectors, Nakashima’s hand-carved wooden chairs and tables are among the most highly sought-after midcentury pieces on the resale market. The unique blend of modern design and traditional materials in Nakashima’s work left an indelible impact on the field of furniture design, and pieces crafted at the studio during his lifetime fetch upwards of $100,000 at auction.

Nakashima Woodworkers became famous for its signature model of “Conoid” chairs (an engineering feat unto itself with two legs supporting a cantilever seat) and wooden tables that are either made from a single cut slab of wood, or two sections of the same tree cut and book-matched to create a mirror image surface.

Rather than shying away from wood pieces with burls or other imperfections, Nakashima highlighted their natural beauty in a manner that is consistent with the Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi, which is sometimes described as one of beauty that is “imperfect, impermanent and incomplete.”

The Nakashima design process indicates a unique blend of engineering, craftsmanship and profound admiration for materials in their natural state — the latter being a trait that Nakashima adopted from his Japanese woodworking mentor Gentaro, whom he met at the Minidoka Relocation Center.

“The experience in the camp was catalytic,” reflected Mira Nakashima of her father’s wartime experience. “You had to rely on whatever you had inside you to survive there. For many years, my father wanted to thank the man who taught him so much about Japanese carpentry while he was in camp, a Japanese national trained in Japan as a master woodworker. He wanted to thank him for teaching him all that he taught, but he was gone by the time he found him. Instead, he found some of his relatives, and they said, ‘Yes, they remembered somebody named Nakashima who used to work with their grandfather.’ Dad was eternally grateful to this Japanese carpenter for working with him, working alongside him.”

In 2018, Mira Nakashima was bestowed the Lifetime Achievement Award as part of Governor’s Art Awards. (Photo: Rob Buscher)

Prior to his encounter with Gentaro, Nakashima had spent little more than a year working part-time as a furniture maker in Seattle. In his early career, Nakashima had begun making a name for himself as a modernist architect, working in Japan for Czech American architect Antonin Raymond, who himself had apprenticed with Frank Lloyd Wright. Ironically, it was actually Nakashima’s distaste for a Wright project that discouraged him from continuing in that field.

“When Dad came home in 1940 just before he got married, he was looking for a job in the U.S. with an architect, and he saw a Frank Lloyd Wright building under construction,” Mira Nakashima recalled. “He did not like the way it was being done, did not like the way architecture was being practiced in the U.S. and he decided he would leave architecture.”

As fate would have it, the Raymond connection was also what allowed the Nakashimas to leave Minidoka.

After his time in Japan, Raymond bought a small farmhouse in Bucks County, Penn. When a mutual friend alerted Raymond of the Nakashima family’s plight, he issued a letter to sponsor George and his family for early release from camp.

The Nakashima family was invited to settle on a section of the farm property in 1943, and in 1945, they purchased an adjacent plot of land that would become the grounds of the Nakashima Studio.

A cantilever staircase designed and built by George Nakashima (Photo: Rob Buscher)

Today, the property itself offers valuable insight into Nakashima’s design process, which took multiple decades of planning and construction to fully realize his vision.

Although Nakashima stopped working professionally as an architect, he designed and oversaw construction on all of the structures on the property. The result: an incredible study of modernist architecture that fully integrates geometric shapes and poured concrete into the rural Pennsylvania landscape.

Indeed, the entire grounds of Nakashima Woodworkers emanates a presence of George Nakashima’s lasting impact on the studio. Perhaps his greatest legacy lives on in his daughter, Mira, who followed in his footsteps as a woodworker. Since her father’s passing in 1990, she has served as creative director of the studio.

JACL members had the privilege of touring Nakashima Studios with her and other members of the Nakashima family, including Mira’s brother, Kevin; daughter-in-law, Soomi; and grandson, Toshi — all of whom are involved with the family business.

Our tour began with Mira giving a brief history of her family’s experiences during their wartime incarceration. Musing on her relationship to the incarceration, she explained, “I wrote my book on Dad’s life and work, which was published in 2003. There was a book tour that took us to Sun Valley Idaho, and I looked at the map and thought, ‘Huh, that’s kind of close to where we were during the war,’ so I went down and visited Minidoka. They didn’t have much there, it hadn’t been designated a national monument yet. That was my first awareness of the camp situation. I had this eerie feeling that I had been there before, but I didn’t remember a lot. I’m still learning about it. My parents, my grandparents — no one would talk about it.”

Our group included several incarceration survivors, who were then inclined to trade their own anecdotes in an informal discussion that helped break the ice. Sharing stories from an experience that only other Japanese Americans could truly relate to, our visit took on a welcoming community atmosphere to it as we felt more like guests than visitors.

Like her father, Mira, too, started her professional journey as an architect.

“When I went to college, I was interested in all kinds of things,” she said. “I was thinking that I would major in music or linguistics, and my father said, ‘No, you’re majoring in architecture,’ and I thought, ‘Ok, well he’s paying the bills, I guess I can do this.’ It seemed OK because I was interested in both math and art, and it kind of tied the two together.”

Mira also had the opportunity to spend time in Japan as she went to graduate school at Waseda University in Tokyo, reliving similar experiences as her father.

“I actually stayed in the same family home that my father lived in when I was at university,” Mira recalled. “It was the Iida family, which was my paternal grandmother’s family home. She was born in the house that dad stayed in and I stayed in, and my oldest son actually stayed with the same family in Kamata.”

Despite these shared experiences, Mira never planned to become a woodworker.

“After Japan, we lived in Pittsburgh for three to four years, and then dad bought this property and said he was going to build a house and asked if I’d like to come home,” she said. “I didn’t think I wanted to come home; I kind of liked not being home — being independent, but my ex-husband said, ‘House and property? Yeah, sounds like a good deal to me!’ So, I came home, and I was able to work part-time in the shop. It was kind of a natural transition.”

Accomplished architect and woodworker Mira Nakashima with Rob Buscher (Photo: Hiro Nishikawa)

When asked what made her decide to pursue woodworking, Mira answered jokingly, “It was a job. And it was right across from my house!”

Now, she is recognized for her own contributions to the field, having recently surpassed her previous auction record when her walnut dining table and set of eight Conoid chairs sold for $150,000 at Freeman’s design auction in Philadelphia.

Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf also bestowed Mira with the prestigious Lifetime Achievement Award as part of the 2018 Governor’s Art Awards, an accolade that she shares with her father as the only other Asian American to win this award.

Ever humble, Mira did not bring up these topics during the tour and instead found ways to connect with the JACLers in a shared community experience. The most impactful moment of the tour came when Mira showed a work-in-progress that she was preparing for the Minidoka National Historic Site. The wooden monument that was since unveiled at the 2019 Minidoka Pilgrimage in July was constructed of polished bitterbrush that was foraged during the incarceration.

The pieces carried a tragic history in them as they were found with the body of Takaji Ed Abe, an Issei man who lost his way back to camp while gathering firewood in December 1942. The Dec. 5 issue of the Minidoka Irrigator wrote of the discovery, “Hatless, the elderly man lay in a horizontal position, head resting on a pillow of sagebrush, both arms laying on his breast. His hands were clenched and his eyelids were closed as if in sleep, the greasewood, for which he ventured alone into unfamiliar land, was at his side.”

Abe perished as the nighttime temperature fell below freezing without shelter in the barren winter landscape. Knowing the Nakashima’s connection to Minidoka, a descendant of Abe approached Mira about creating a monument using the wood his family had saved for more than seven decades.

At this year’s Minidoka Pilgrimage, Mira dedicated the monument that now resides in the visitor center at Minidoka to all those who perished during the incarceration. It seems a fitting tribute, conceived by a master artist who has not only continued the work that was started by her father, but also built an impressive legacy of her own.